Written by Dr. Glenis Benson, a lifelong autism professional.

*Identity first language (IFL) will be used throughout, not

“The single biggest problem with communication is the illusion that it has taken place.” George Bernard Shaw

Introduction:

Although communication impairments are a core defining component of ASC, to date, there has been insufficient focus on the comprehension of spoken language. Typically, expressive abilities are targeted for intervention; thankfully, there has been a recognition that autistics must have a means by which they can express their needs, be it verbal or with the aid of some augmentative alternative communication (AAC) method.

Their ability to understand what is said to them has not been so closely investigated. Sure, there is a recognition that many are very literal, and it is well understood that idioms and metaphors may be challenging, but all too little thought has been given to the general,

Understanding matters!

Intended Audience:

This toolkit is designed to sensitize parents of children of all ages, teachers, and

Rationale for this toolkit:

If there is truly an issue with language comprehension, why is there not greater recognition of this problem? The answer is that it is complicated.

A.Often autistics are able to complete a verbal directive giving rise to the conclusion that they have understood the spoken words, but frequently there are alternative explanations; there are means by which they can complete the task without understanding the words. When we give directives we often tap and/or point to augment our verbal message; autistics may be attending to these visual prompts to assist with the completion of the directive.

A developmental pediatrician, known for diagnosing masses of children in her day, required trainee resident physicians to keep their hands in their pockets so as to NOT inadvertently provide visual cues that would aid in the individual’s understanding of the questions being asked of them. She wanted the residents to understand that they could be giving ‘clues’ if their hands were not otherwise in the pockets of their lab coat thereby allowing the individual to follow a directive even though they had not understood the spoken word

Consider Hunter, an autistic kindergarten student. I had observed Hunter in his kindergarten classroom on a couple of occasions and hypothesized that his understanding of the teacher’s spoken words was highly suspect. His father, however, explained that Hunter understands everything, and then he provided me with this example. He explained that in the morning when they see the school bus coming down the lane, he can say, “Clean up your dishes and get ready for the bus” and Hunter follows through, faithfully every morning.

Is this evidence that Hunter understood his dad’s language? Not necessarily.

There are multiple explanations for Hunter’s ability to follow this directive:

|

B.Many directives are repetitive; we say the same thing every day especially when it comes to personal care and household routines. Perhaps the autistic individual has learned the routine as a function of the context, independent of the verbal directive (e.g., I see the bus, so I engage in my ‘leaving for school’ routine). They can also appear to have understood the spoken words especially in the classroom, when in fact they are imitating their 25 classmates. Then again, sometimes autistics can infer the intent of the speaker by comprehending only the nouns in the directive; nouns are concrete and can be visualized unlike words that are abstract for which a picture cannot be made in one’s head (more about thinking in

C.Formal

An SLP provided the results of her assessment of a young man with autism. She explained that she conducted a formal assessment of his receptive language and concluded that his abilities were within the norms for his age. However, he could not understand the teacher in the front of his classroom. Informal as well as formal assessments must be conducted to get a complete picture of someone’s abilities; until we acknowledge the deficit it will go without remediation.

Why beat this drum relentlessly?

Why erode the competencies parents/teachers/caregivers ascribe to those with ASC?

Aren’t we supposed to presume competence?

If you believe that the autistic comprehends EVERYTHING you say, and if they happen to respond intermittently or fail to respond to a directive, you need an explanation for this behaviour. Unfortunately, too often the explanation is that the autistic is being

The explanations are numerous for how they can appear to have understood what has been said to them, even when they have not in fact grasped the meaning of the words spoken. The problem arises when they do not complete a verbal directive, and it is believed that they have understood the directive. If you believe that the autistic comprehends EVERYTHING you say, and if they respond intermittently or fail to respond at all to your directives, you need an explanation for this behaviour. Unfortunately, all too often the explanation is that the autistic is being

“Kids do well if they can.”

– Ross Greene

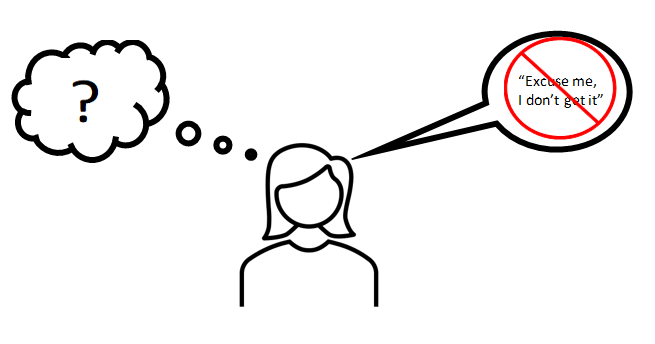

The story doesn’t end there. Clinical anecdotes report that autistics rarely request clarification; they very rarely indicate that they have not understood something. If they regularly inquired “what do you mean?” or stated “I don’t get it” they would be signaling their comprehension failures, but they tend not to give their communication partner such feedback. In the absence of such feedback, communication partners make assumptions that comprehension has taken place. Sometimes someone may check for comprehension by asking, “What did I just tell you?” which, for an echolalic autistic proves nothing about their understanding, but rather how well they can repeat.

Even when comprehension has not taken place, autistics rarely REQUEST CLARIFICATION The literal and/or echolalic autistic individual may simply REPEAT; this doesn’t mean that they’ve understood.

The literal and/or echolalic autistic individual may simply REPEAT; this doesn’t mean that they’ve understood.

Would it not be a tragedy if in fact we are assuming that they understand when in fact they do not? The consequences of this misunderstanding are the motivation for this toolkit. Autistics deserve our understanding and our assistance.

The ‘watch & listen’ opportunities should be completed with your favourite autistic person. Engage them in the activity to get a

Intent of the Toolkit:

The objectives for those who access this toolkit are:

- To understand the potential for language comprehension difficulties;

- To question the comprehension of someone they previously believed understood most things;

- To employ strategies to improve understanding;

- But most of all, to eliminate the assumptions that the autistic is being

NON-COMPLIANT, DEFIANT, or OPPOSITIONAL when they do not follow a directive.

Autistic characteristics that contribute to the problem

Although what follows is rather technical, it is imperative to understand the various components that contribute to understanding spoken language; it is truly a complex task.

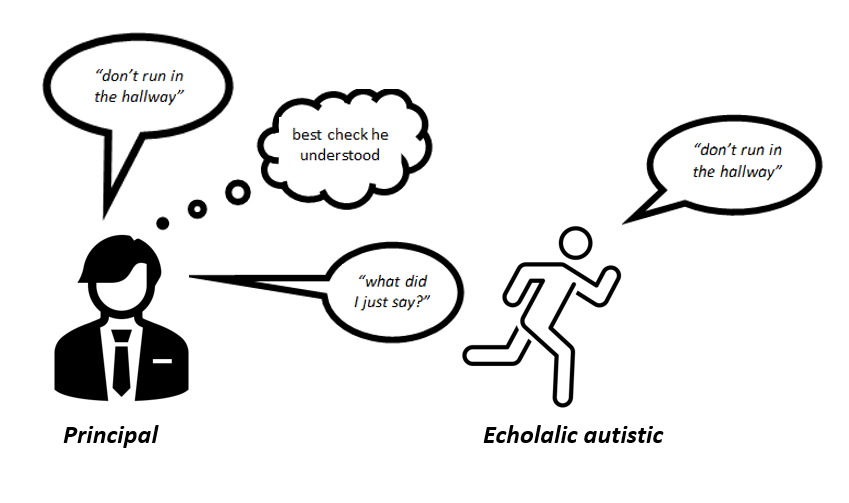

| The autistic characteristics that should have alerted us to the potential for comprehension challenges abound. Frankly, we should have been sensitized to this potential problem all along. When we examine autistic characteristics, it becomes evident that understanding someone who is talking can be exceedingly difficult, especially long strings of directions, questions or conversations. There are so many autistic characteristics that can potentially impact the understanding of spoken language and cause communication problems. |

Processing Speed: A major culprit in understanding spoken language for autistics is their fundamental deficit in processing what they hear. It is not the inability to hear, per se, but rather, it is the brain’s ability to process or make sense of what is heard. Auditory processing deficits contribute to language difficulties in autism.(1) Slow auditory processing speed (2,3,4)

Short-Term Memory: When autistic memory is discussed, many immediately relate tales of extraordinary recall. There is the British autistic artist Stephen Wiltshire who drew the skyline of NYC following a helicopter flight over the city. Many people know autistics who can recall events such as every meal ever consumed in their 52 years on the planet. We all know someone whose memory astounds us. Subsequently it can be erroneously concluded that memory is unencumbered in autism. But it is overly simplistic to believe all have great memories because memory is not just one construct; it is imperative to distinguish between short-term memory (STM) and long-term memory (LTM).

A recent meta-analysis on memory in autism revealed that there is a difference between STM and LTM.(5) In autism, LTM is basically preserved; autistics have few deficits in LTM (e.g., remembering every meal ever consumed). The same cannot be said for STM (e.g., remembering what you were told to retrieve from your room), in fact the authors are explicit in their call for support of STM in ASC. This explains why autistics struggle to retain our directives when we tell them more than one thing at a time; this is also why ‘first then’ setups can help. It is also critical to realize that STM deficits occur regardless of IQ so believing he’s so brilliant, of course he ‘got that’ could be erroneous and misleading.

WATCH AND LISTEN: Give a string of multiple consecutive directives to your favourite autistic and watch for their ability to comprehend/retain/follow through (e.g., change your clothes, brush your teeth, use the toilet and meet me in the garage). Now add a directive that you know they will not understand (e.g., go get your satchel). Do they ask you to clarify, or ask you what you mean, that is, do they request clarification? |

Attention: Attentional difficulties characterize many with ASD. Indeed, the rate of those with ASC who present with comorbid symptoms of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) varies from 35%6 to 85%.(7) The specific aspects of attention that pertain to communication are social orienting (spontaneously turning toward the social signal) and joint attention (coordinating gaze as in following someone’s point or eye gaze).(8) Social orienting and joint attention are sufficiently impaired in ASC such that 76% of children with ASC could be correctly classified on these variables alone. Failure to orient to the source of spoken instructions or directives would suggest that following said directives could well be compromised. We have got to confirm their attention but know that does not mean that they must be looking at you.

Prosody: Prosody is the rhythm and melody of speech and when it is impaired the listener’s ability to understand and communicate is compromised.(9)

Expressive abnormalities in prosody are common in autism(10) but so are receptive differences. Interpreting affective and linguistic prosody is compromised in ASC thereby adversely affecting the understanding of spoken language in autism.(11,12,13) Clinical anecdotes abound of autistics misunderstanding prosody, volume, as well as intonation (e.g., “why are you yelling at me?” – when you are not yelling, or “he’s being mean” – when the emphasis or intonation was misunderstood).

Consider this Example:

I wouldn't say you are late (not me)

I wouldn't say you are late (never)

I wouldn't say you are late (Just think it)

I wouldn't say you are late (others are)

I wouldn't say you are late (but close to it)

I wouldn't say you are late (something else)

Concreteness TiP: Comprehending language can be difficult for individuals with ASC; often it’s easier for them to understand what they see.(14) Temple Grandin(15) tells us that she is generating pictures in her mind for every noun she hears. She thinks in pictures (TiP). But she is not alone. Kunda and Goel(16) found that TiP represents a very powerful way to look at cognition in autism. One can generate a picture in one’s head for things that are concrete (e.g., most nouns), however, things that are abstract (e.g., words like sadness, or concepts such as the passage of time) cannot be visualized. Grandin actually claims that if you cannot make a picture in your head, of the word, that the autistic will struggle to undersatnd it. (14)

“Words are like a second language to me. I translate both spoken and written words into full-color movies, complete with sound, which run like a VCR tape in my head. When somebody speaks to me, his words are instantly translated into pictures.” “Autistics have problems learning things that cannot be thought about in pictures. The easiest words for an autistic child to learn are nouns because they directly relate to pictures.”

Temple Grandin

How can we improve understanding?

Keys to speaking to those on the spectrum (recognizing of course the great variability across all who are so diagnosed), are the following:

- Speak slower and avoid long strings of verbiage; make it ONE directive, not more, and give wait time… a lot longer than one would think.

- THINK of the words you are using; can you make a picture of the words you are using? “Cleanup” to a

middle-aged autistic woman meant sweep the ceiling, so use words that convey what you want them to convey. Does the picture in their head match the intention of your words? “Pick up the floor” “I need your eyes up here” “take a seat” “give me your hand”; for the literal listener, their understanding does NOT MATCH your intent. Please know that sarcasm is just unwelcome. - Emphasize the concrete; avoid abstract words altogether or compensate with visuals. Visual timers, visual schedules, visual calendars, visual routines, speaking bubbles, thinking bubbles – let the pictures convey the message.

- What do you think they understand by words such as ‘later’ ‘soon’ ‘wait’ ‘maybe’? After all, you cannot make a picture in your head; these are totally abstract, and arguably very difficult for the autistic to comprehend. This list is LONG.

- Loud, emotional volume will render the message content superfluous; they will focus on the volume and the anger – comprehension fail.

“Another indicator of visual thinking as the primary method of processing information is the remarkable ability many autistic people exhibit in solving jigsaw puzzles, finding their way around a city, or memorizing enormous amounts of information at a glance.”

Temple Grandin

| WATCH & LISTEN: Do they notice the slightest visible change? Glasses on/off, hair up/down, throw cushions in ‘wrong’ place? Do they know the route to grandma’s house? For children, do they arrange their toys TO PLAY and if you move something… well, just don’t move anything! Do they complete puzzles upside down? Just HOW visual is your favorite autistic? Think back. Try some visual changes. |

Not everyone with ASC will experience the above challenges to the same degree, however, individuals on the spectrum often have strengths in visual learning.

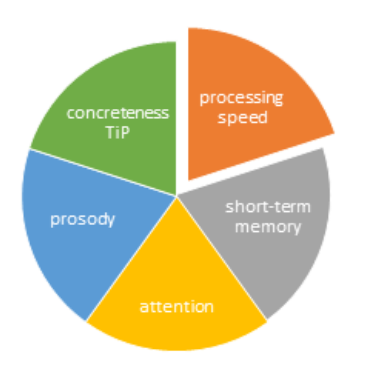

Visual communication totally eliminates issues with processing speed, short term memory, prosody, volume, and intonation, and it plays to the ASC strength as visual learners.

What is meant by VISUALS?

•For our purposes here, think of augmenting or replacing the spoken word, by adding a component that can be seen.

•A ‘visual’ can take many forms: objects, pictures/photographs, line drawings, print (text), facial expressions, even gestures are all considered visuals.

Please do not WEAN off visuals! This is not a goal!

We all use visuals to some extent, be it the calendar on our smart phone or the

Rather than weaning off them, they can be made more sophisticated, they can even be integrated into technology, but the goal is NOT to eliminate their use.

What kind of visual should I use?

When designing a communication system for an individual, the visual representations must be understood; this is not an arbitrary exercise of selecting what is easiest or preferable for the speaker. We know this well when we design expressive systems. Whether the system is low or high tech, the visual representation must be understood, or able to be learned by the communication partner. Of course, this is true for promoting understanding as well.

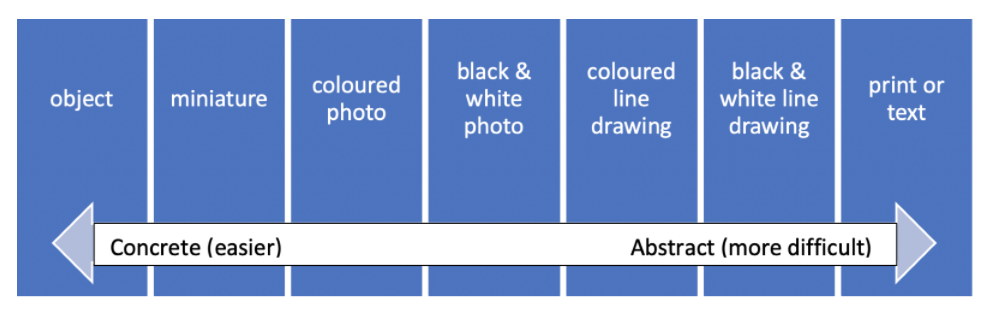

Historically we have relied on a ‘visual hierarchy’ and ‘iconicity hierarchy’ that provides a continuum of symbol understanding, from concrete (easier) to abstract (more difficult). The object or concrete end of the continuum can be thought of as “transparent” or “iconic” (e.g. an actual apple) while the print or abstract end can be thought of as “arbitrary” or “opaque” (e.g. the printed word ‘apple’).17 This hierarchy is not absolute, for instance, some find line drawings easier to comprehend than photos, however, this can be used as a guide in determining how best to provide visual support. You need only determine what symbol level works best for the individual for whom you are providing the visual support.

When should I use visuals:

Comprehension failures occur in all contexts. Some situations, however, lend themselves more readily to providing visual supports. For instance, there is a distinction between social interactions, and

If the goal is to get the deed done, or to convey critical information, then the directions truly do not need be spoken; you may want to augment the visual with spoken language, as opposed to the other way around.

Parent: “You don’t understand, I’ve told him eleventybillion times!”

Me: “Oh, I know, and that my friend IS THE PROBLEM!”

TALK LESS SHOW MORE

Another consideration when selecting the type of visual, has to be the lasting nature of the communicative signal; the spoken word is fleeting, once said, it is gone, no longer accessible if one needs to refer to it to confirm comprehension. The brevity of this signal contributes greatly to comprehension difficulties when the autistic experiences slow auditory processing as well as STM difficulties. The words are spoken and GONE; they are no longer available.

Visuals can also be fleeting as in a point, a gesture, a facial expression. Like the spoken word, when a visual is of a fleeting nature, the autistic individual cannot access it over time. The stability of the visual signal is a critical element; if a fleeting visual is used, the issues with processing speed and STM have not been addressed. Therefore, when creating visual supports, the notion of signal durability is important. The more useful visual support will be stable (like directions on a dry erase board, a picture schedule, a visual

Sawyer was just finishing 8th grade; he was high school bound. He had done well in school so far; he had been fully included and required only minimal supports for his autism. I asked if he had a favourite teacher from 8th grade hoping to glean what worked and what did not. Without hesitation he declared that his favourite teacher was his favourite because she wrote both the day’s agenda and the homework on the board.

STABLE VISUAL CUES made her his favourite teacher!

Some hear ‘visual communication’ and their minds leap to sign language. Indeed, it is visual, but there are so many elements of sign language that do not address autistic communication limitations. Sign language is incredibly abstract, it is fleeting thereby not addressing the processing or STM challenges. Sign language is not the answer to this problem.

What type of visual will work best? Line drawings? Photos? Black and white or colour? This is your first decision. Now create the pictures or start drawing on a dry erase board/paper.

Intelligence level and verbal ability

have little to nothing to do with

using visuals to increase understanding.

In the course of an autistic’s day, what circumstances present the most opportunities for miscommunication with the autistic?

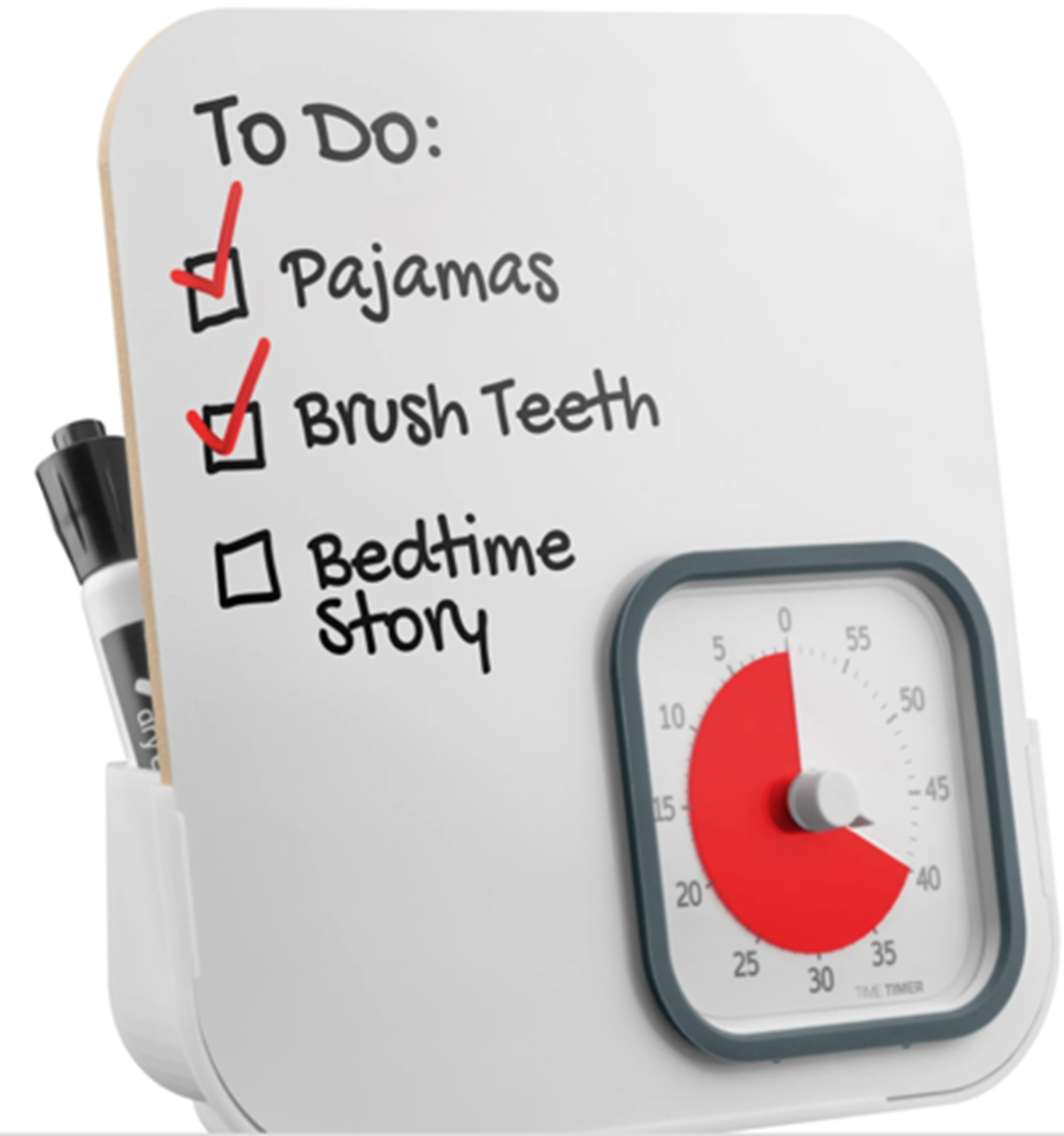

Directives: directing them to complete some action in a manner they can comprehend Much of what we do in a day is a repetition of the previous day. We have daily routines like morning/evening hygiene/dressing/undressing, the routine for leaving for school/work, as well as the routine completed upon your return. All of these routines lend themselves to visuals. When visuals are used, not only do you eliminate the potential for miscommunication and misunderstanding, but you also actually increase independence. If the individual can follow a visual routine/checklist/schedule, eventually they do not need you there by their side.

- Visual routines/checklists are critical because of the STM issues. These routines may have been practiced/completed given our verbal prompting a couple of times a day for years, but autistics routinely say they need to be reminded each and every time.

Directives – giving directions (e.g., “get in the car,” “get ready for bed,” “clean up the toys”)

Example A: (written schedule)

| This is an example of a written schedule for campers where all could read and understand the words. This would replace: “at 7:30 we have the Polar Bear plunge, followed by bug/sun protection, then meds at 8:05, followed by setting the table at 8:15, and breakfast at 8:30. Then at 9:30 we go fishing, with snack at 10:15, and waterfront at 10:30 and Fun Hill at 11:30.” |

This is an example of a written schedule for campers where all could read and understand the words. This would replace: “at 7:30 we have the Polar Bear plunge, followed by bug/sun protection, then meds at 8:05, followed by setting the table at 8:15, and breakfast at 8:30. Then at 9:30 we go fishing, with snack at 10:15, and waterfront at 10:30 and Fun Hill at 11:30.”

Example B:

| In this example, there are black and white line drawings indicating that the child would go to music, followed by lunch, followed by recess, and the TimeTimer™ indicates the time to transition to the next activity. This visual would replace written words. |

Example C:

| In Example C, there is a written schedule that can be checked off when completed with an integrated TimeTimer™ that indicates the total time allotted to the entire activity. |

Example D:

| In example D, there is a black and white line drawing used instead of words (Example C) for someone who would better understand pictures than words. |

First/then

Their application is endless (insert photos, line drawings or words):

First: dinner Then: board games

First: snack Then: brush teeth

Feel free to make a sign and hang that reads: (Why Am I Talking?)

While much of what we say is directing the autistic to engage in

day-to-day activities, a lot of communication involves responding to their requests, to their inquiries which puts us in the role of responder.Responses: Responding to their requests in a manner they can comprehend

oAffirming – rarely when you comply with a request is there difficulty, but

oDenying/delaying compliance with a request is what will typically cause grief (much of the time because the response has been misunderstood)

oThe answer to any ‘when’ question has to be visual because you cannot visualize temporal terms.

Denying:

“No” would seem to be fairly straightforward response to a request but actually ‘no’ has multiple meanings and truly it’s open to misinterpretation for the autistic individual.

| When the adult says: “No” - permission denied (e.g., “you cannot have screen time”) “No” - it’s all gone (e.g., “no more Cinnamon Crunch, I’m sorry”) “No” – refusal (e.g., “I won’t open that up”) “No” – negation (e.g., “I don’t want that”) |

But it is even more problematic because when we say something like “no more screen time” we mean for RIGHT NOW, but to interpret it that way you must bring a level of social understanding, and perceived intent to the situation. If, like the autistic, you rely solely on the word meaning, you conclude that NEVER, EVER, EVER will you get screen time EVER AGAIN, IN YOUR LIFETIME – cue meltdown – caused by a communication failure.

It would be preferable to say ‘yes’ (when has yes caused a meltdown?) and then show with a timer, a schedule, a calendar WHEN the request can be satisfied. Once this approach is used and the autistic individual learns to trust that you are predictable, they tend to be more accommodating of those requests to which you can never say ‘yes.

Delaying – answering their demands/questions with responses such as (e.g., “maybe,” “later,” “soon,” “wait,” “tomorrow,” “in 5 minutes,” “this afternoon”). While these are very common responses, what they also have in common is their ABSTRACTNESS. Can you make a picture of any of those words? No! We who understand language well, can erroneously believe these responses to be incredibly simple, but to the autistic they are anything but simple. Granted they are brief, and if you have been paying attention to this point you have gathered that cryptic, short responses are desirable (they don’t tax auditory processing or STM), but the response still has to be understandable, which many of the above are not.

Passage of time is VERY abstract, so it is imperative to use visuals to show passage of time.

Minutes/hours : use a visual timer (not digital), and the TimeTimer™ o Hours/days/weeks : use a visual schedule, calendar

In conclusion

You need not do this alone. SLPs are

Proceed with the understanding that comprehending spoken language is no easy task for an autistic. But know, that now that you are armed with this awareness, you can enhance their understanding and improve your communication with them.

References

1.Marco, E. J., Hinkley, L. B., Hill, S. S., & Nagarajan, S. S. (2011). Sensory processing in autism: A review of neurophysiologic findings. Nature Publishing Group.

2.Arnett, A. B., Hudac, C. M., DesChamps, T. D., Cairney, B. E., Gerdts, J., Wallace, A. S., Bernier, R. A., & Webb, S. J. (2018). Auditory perception is associated with implicit language learning and receptive language ability in autism spectrum disorder. Brain and Language, 187,

3.Haigh, S. M., Walsh, J. A., Mazefsky, C. A., Minshew, N. J. & Eack, S. M. (2018). Processing speed in impaired in adults with autism spectrum disorder and relates to social communication abilities. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48,

4.

5.Desaunay, P., Briant, A. R, Bowler, D. M, Ring, M. Gérardin, P., Baleyte, J., Guénolé, F., Eustache, F., Parienti, J., &

6.Gadow, K. D., DeVincent, C. J., Pomeroy, J., and Azizian, A. (2004). Psychiatric symptoms in preschool children with PDD and clinic and comparison samples. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 34,

7.Lee, D. O., and Ousley, O. Y. (2006).

8.Dawson, G., Meltzoff, A., Osterling, J., Rinaldi, J., & Brown, E. (1998). Children with autism fail to orient to naturally occurring social stimuli. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 28,

9.Loveall, S.J., Hawthorne, K., Gaines, M. (2021). A

33285421.

10.Baltaxe, C. A. M., & Simmons, J. Q. (1985). Prosodic development in normal, autistic children. In E. Schopler, & G. Mesibov (Eds.), Communication problems in autism (pp.

11.Kujala, T., Lepisto ̈, T.,

12.McCann, J., & Peppe ,́S. (2003). Prosody in autism spectrum disorders: A critical review. International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders, 38,

13.Paul, R., Augustyn, A., Klin, A., & Volkmar, F. R. (2005). Perception and production of prosody by speakers with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 35,

16.Kunda, M., & Goel, A. K. (2011). Thinking in pictures as a cognitive account of autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders.