Evaluating research for yourself: How to find, interpret, and weigh evidence in science articles

By Dr. Fakhri Shafai

Understanding scientific research can take years of training for graduate students, let alone the average person who is trying to learn about a specific scientific topic. Without a basic understanding of how to interpret research articles, it is possible for people to misunderstand the research results and put too much/not enough emphasis on any conclusions they can draw from them.

Part of AIDE Canada’s mandate is to provide information so that individuals and families can make their own informed decisions. We are creating this guide as a basic introduction to finding peer-reviewed research on a topic that is important to you and tips on how to interpret studies. We will use one of the most widely used tools for finding research studies, Google Scholar, and give examples of what to look for when finding studies of interest. We will also provide examples of what to look for once you are reading a study.

Why does peer-review matter?

When scientists say something is “peer-reviewed”, this means that the article was sent to experts outside of that scientist’s immediate circle (e.g., they don’t work together). These peers are also experts in the same field and have the job of reviewing the study before making recommendations to the publishing journal as to whether they should accept the paper, accept it once revisions (edits) have been made, or if they should reject the article entirely. These experts often provide extensive feedback to the authors so they know what needs to be changed before they should resubmit the paper or submit it to a different journal.

Examples of reasons a reviewer may ask for revisions can include things like needing to do a statistical analysis a different way, needing a follow-up experiment to make sure that the findings are stable, or needing to reword their discussion/conclusions as they are making too strong a statement about the importance of the findings.

Examples of reasons a reviewer may reject a research study from publication can include flaws in the study design or analysis of data collection so the results cannot be trusted, the research is not novel and original (e.g., someone else has already published something similar), or the conclusions do not match what the results actually say.

Most journals have at least two peer-reviewers for any papers that are published. It often takes several months between the time a researcher submits their study for publication and them finding out the journal’s decision. The authors then can take several months making the necessary changes to the article. It may take up to a year between when the paper was sent to a journal and when it is published online.

Why do I need to know this? Why can’t I just use a trusted science reporter?

Science reporters are people with a background in science who are well-versed in breaking down difficult scientific concepts for the general public (aka ‘lay audience’). Many of them have been doing this for years and feel confident describing a certain range of topics related to their own expertise. For example, a person with training in genetics may feel comfortable writing about recent studies that look at the role a certain gene plays in the brain.

However, with the increase of online-based publications and the ‘gig-based’ economy (where some people write articles for whichever publication accepts them), some science writers do not have much experience writing about certain topics and have misinterpreted or oversimplified findings. Their publication editors may also not have a background in science and so do not know that they are publishing something that is inaccurate. This can lead to some major misunderstandings in the general public.

There are some online publications that are well-known for fairly looking at studies and only drawing conclusions that are supported by the evidence. Spectrum News is an organization that has gained a reputation of excellence in fairly interpreting autism-related research articles and providing important context to controversial topics over the years.

Part 1: How do I find articles on a specific topic?

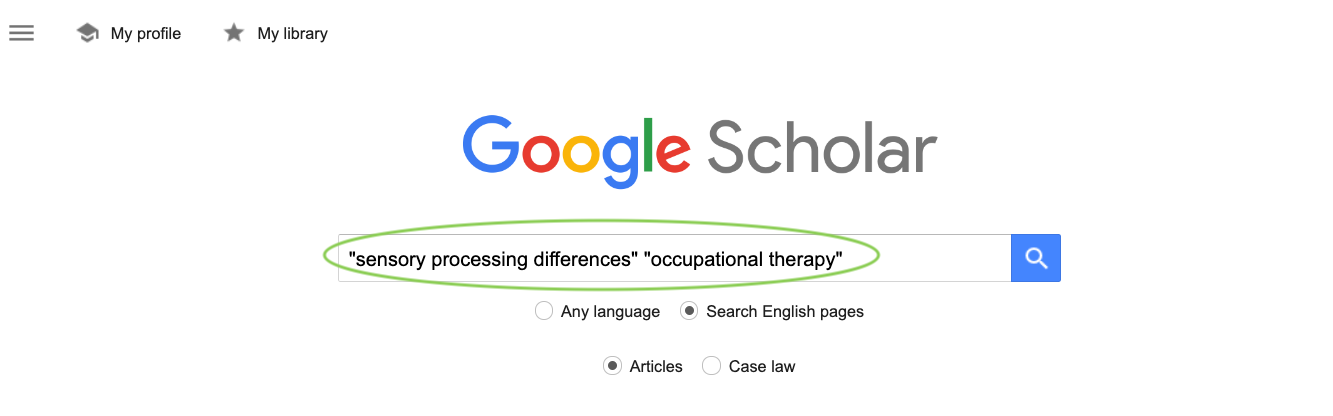

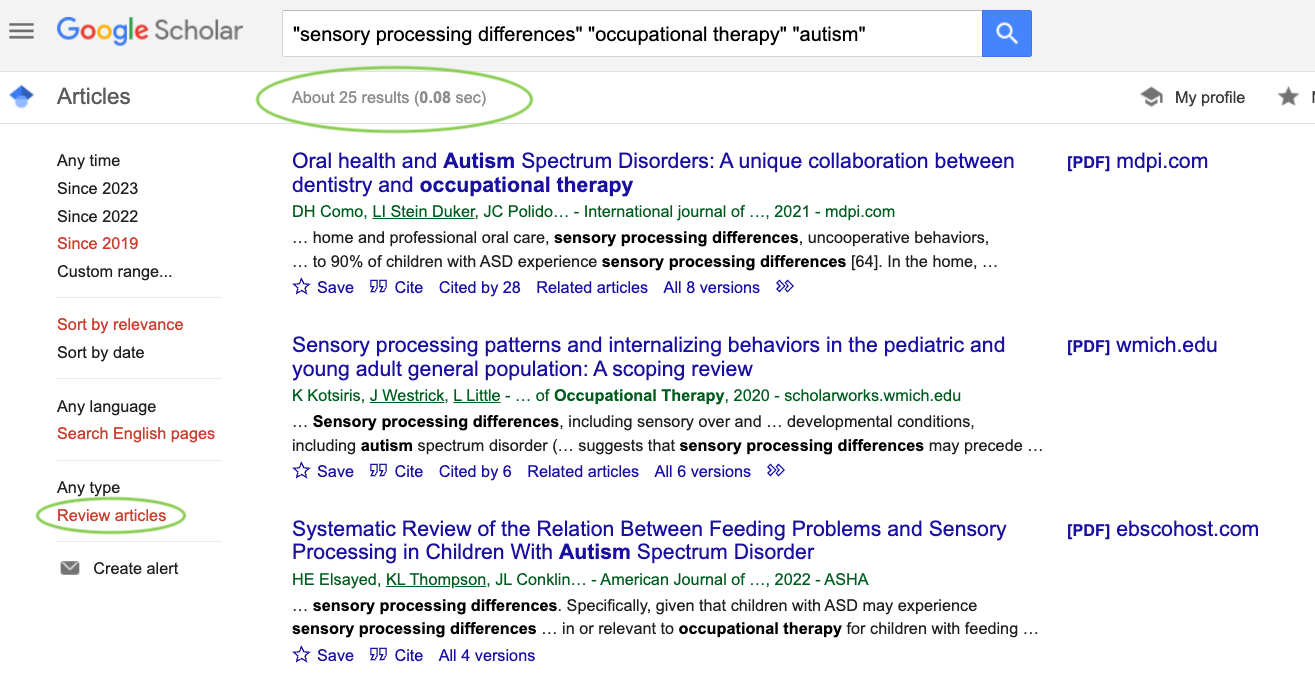

Search Terms: We will be using Google Scholar as our search engine for this guide. Google scholar works similarly to the main Google search engine in that if you put quotes around certain words all the results will contain those words. For the purposes of this search, we will be looking at sensory processing differences and occupational therapy.

Once you click on the search button, you will see a large list of articles. For instance, this search yielded 636 results. You may decide that you want to narrow these down before you begin to look at the articles themselves.

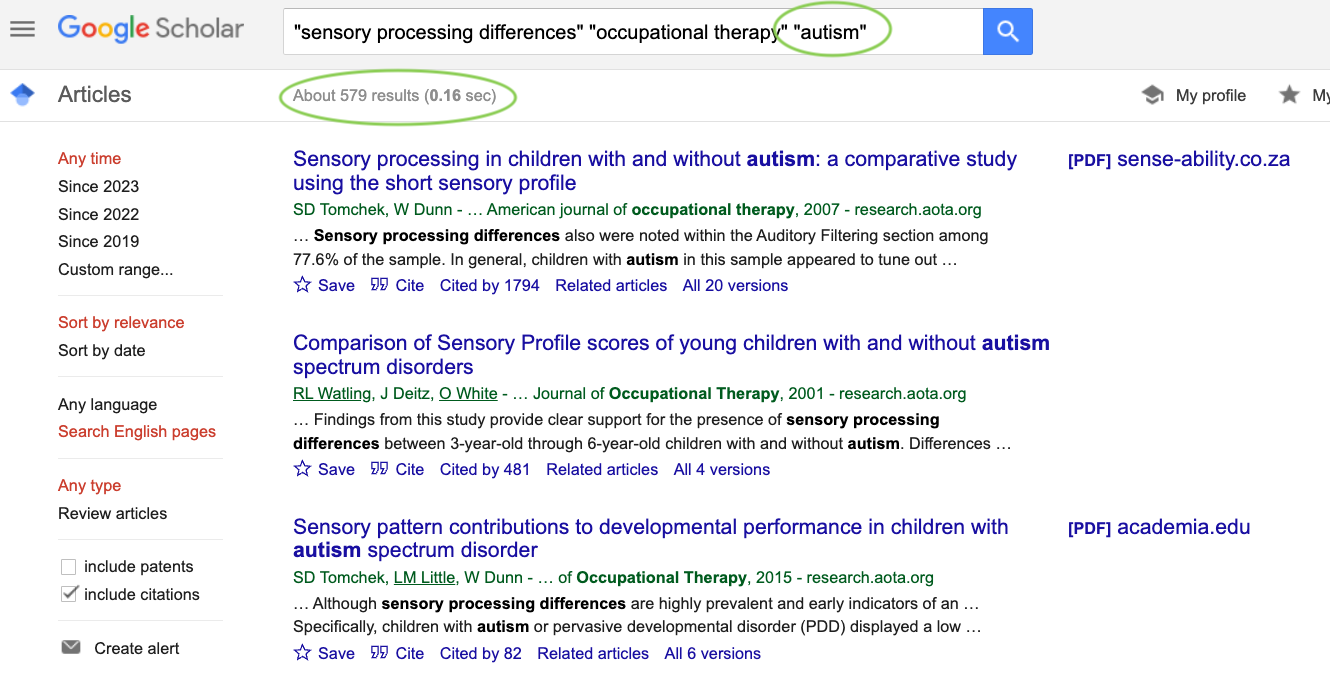

You may choose to add an additional search term with quotes. For instance, by adding “autism” to the search bar there are now 57 fewer articles listed. You can also try adding other search terms like “intervention”, “treatment”, “children”, etc. to help narrow the volume of identified studies even more.

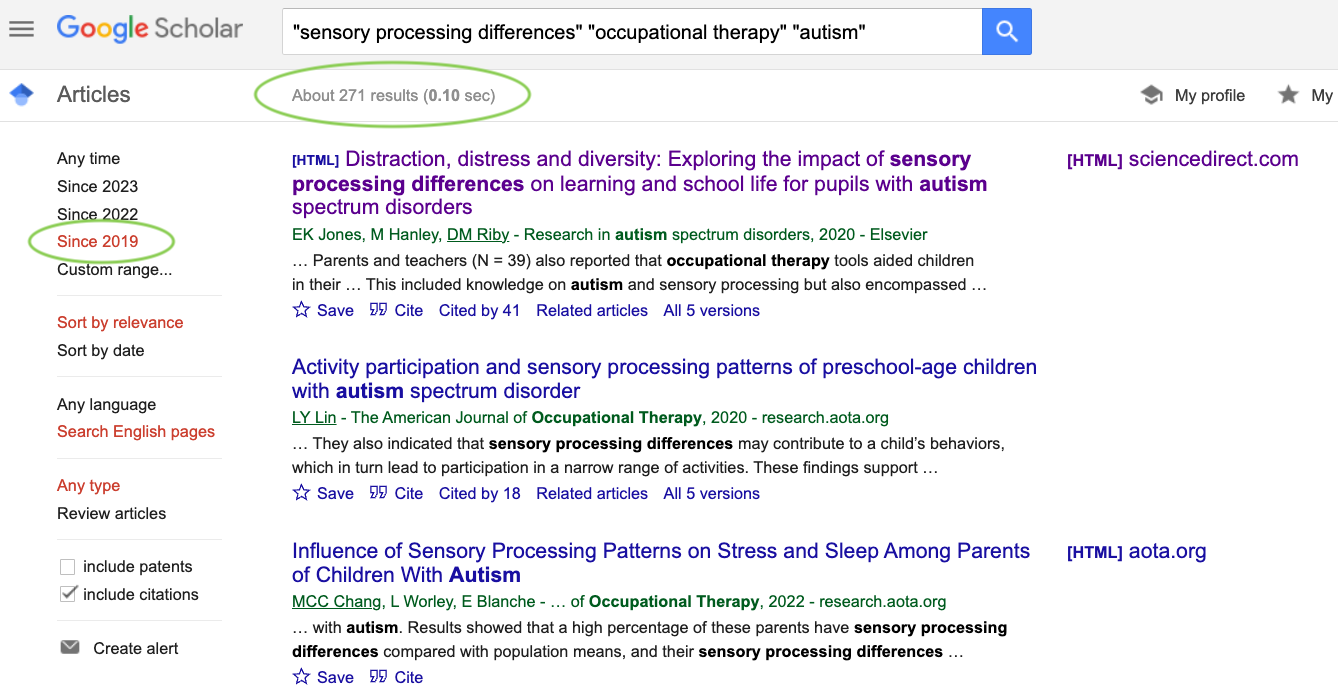

Publication date: In the top left corner of the Google Scholar page there are options for specific dates or the ability to create a custom date range. If you only want to know the latest research, you can choose to select articles that were published within the past 3 years. In this case we have now narrowed the number of articles to 271. Please note that one of the hazards of only looking at recent research is that you may be missing ground-breaking studies that were published more than 3 years ago. It also makes looking at the number of citations (described below) less useful.

Review articles: One fast way to narrow down the number of articles is to choose ‘Review articles’ on the left column instead of ‘Any type’. After selecting ‘Review articles’ we now only have 25 studies listed. Review articles are articles that do not present new research themselves, but instead bring together multiple studies about a topic and describe what sort of conclusions can reasonably be drawn from the research. These articles are especially useful for people who do not know a lot about a topic but want to gain an overview of the research in a given field. Drawbacks to reading reviews is that they often are missing the latest research and look at general trends in the research instead of fully describing and understanding each article included in the summary.

Part 2: How do I interpret and weigh the evidence in the article I am reading?

Once you have found an article you want to read, you will have to figure out how to interpret what it is saying and decide whether the evidence is strong or not. As mentioned before, this is a skill that takes years to develop, but there are some general guidelines we can offer.

Abstracts: An abstract is a brief summary at the beginning of a journal article that describes what was done and the main findings of the study. Abstracts are especially useful to help you decide if you want to read the full article or not. Each journal has their own format for abstracts, but in general, an abstract will include information like:

Background – What is known about a topic and what the study is aiming to add to the science

Methods – What did the researchers do in their study

Results – What the researchers found after collecting data and doing their analysis

Conclusions – What the researchers can say about how their results relate to the topic being studied

Some journals also have a ‘lay abstract’ or ‘lay summary’ often below the main abstract that is written in more accessible language for the general public. This is a relatively new practice, so older articles are not likely to have this option.

Authors: When looking at the authors listed on a study, pay close attention to the first person (name) and the last person (name) listed. The first name is the main author of a paper, usually a graduate student or postdoctoral researcher who ran the study and wrote the paper. Writing the journal article is part of their training. The last author on the paper is usually the senior researcher whose lab the study was conducted from (e.g., the first author’s mentor and trainer) and they made edits and approved the paper before sending it to an academic journal for peer review.

There is usually something called ‘author affiliations’, ‘additional author information’, or ‘show more’ that you can click to find out more about the authors, for instance, which university they are associated with. Other journals have hyperlinks for each author’s names that you can click on and see what university they are from and what other articles they have published.

Some articles will have only senior authors (e.g., no students or trainees). In that case, the first author is usually the person that wrote the bulk of the paper. Some will have a disclaimer saying that multiple authors put in equal work, and they are listed alphabetically, not by order of contribution.

You can look up the author impact factor for the authors listed. Authors who are cited (see below) the most (e.g., their studies are mentioned in other studies) will have higher impact factors. For senior authors (e.g., those listed at the end of the author list), this impact factor can give you a good indication of how long they have been publishing and how many of their peers value their research enough to include mentions of it in their work.

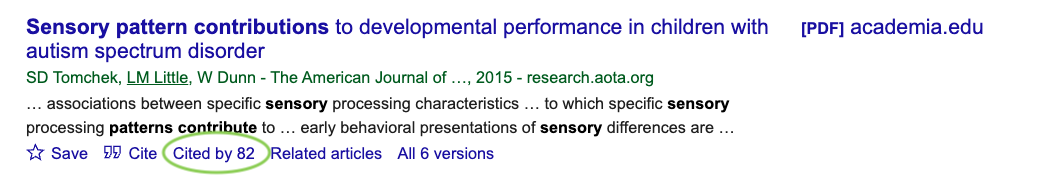

Citations: When a journal article mentions previous peer-reviewed studies, this is called a citation. In general, the more times a journal article has been cited, the more ‘successful’ it is, although this is not always the case. For instance, let’s say Paper X is had findings that were proven to be mistaken. This paper may be cited frequently in future studies because the authors are providing historical context or pointing out the flaw in Paper X’s methods. But, in general, the more citations a study has, the more trusted it is. You can find the number of times a paper has been cited by looking below the title in Google Scholar. For instance, this paper has been cited 82 times as of January 2023. It is important to remember that more recent articles have not had much time to be cited, so looking only at journal articles with high citation numbers may mean that you are not looking at up-to-date findings.

References: The full information about that paper being cited is listed at the end of the article as a reference. References include information about the study like the author(s) names, title of the study, name of the journal it was published in, and publication date. Some journals show citations in the text of the article as last names and year of publication (for example, ‘Smith et. al., 2023) and then have the full reference listed at the end and presented in alphabetical order. Other journals will have the citations listed as superscript numbers in the text (e.g., sensory processing differences are common in autism spectrum disorder1-3) and then the full reference will be listed numerically in the reference section. Many publication journals have a limit of the number of references a paper can include in the reference section. You can look at the reference section to find other articles on the topic that may be worth reading.

Journal Impact Factor: This is a number that is calculated to describe how ‘important’ a journal is in its field. The more times articles in a certain journal are cited in other studies, the higher that journal’s impact factor. In general, impact factors of 10 or higher are excellent, impact factors of 3 are good, and the average score is less than 1 impact factor. The most prestigious journal in the world with the highest impact factor is Nature – with an impact factor of over 69.5 according to bioxbio.com in 2021. It is important to note that journals that focus on a narrow range of topics, are intended for people of a specific vocation (e.g., occupational therapists), or are relatively new journals likely will have lower impact factors than ones that appeal to a wide range of scientists, like Nature.

Number of participants: Some researchers will write a journal article based on a study they did with a group of participants/patients (usually described in the ‘Methods’ section of the paper). In some cases, it is expected to be a low number of people (e.g., a case study done on one or a handful of people). However, if only a small number of people were included in a study, then it is best to recognize that the findings may only apply to a small subset of the population.

I want to read an article, but it costs money! Am I able to access it some other way?

One of the unfortunate aspects of academic research is that many of the articles are behind a paywall. In recent years, there has been a push to publish in ‘open access’ journals, meaning that no one needs to pay to read the articles. This will eventually lead to more studies being able to be accessed by all people, not just researchers. The major federal research funding agencies in Canada now have a policy that any research that uses taxpayer dollars must be made open access within one year of publication. In 2022, the United States Government announced that all studies funded by taxpayers must be made open access as soon as they are published by the end of 2025. This means you can expect more journal articles to be freely available within the next two years.

Researchers themselves do not get money from the paid articles, but the publisher does. Publishers usually have deals with the universities and people on campus whereby students and faculty members can electronically log into journals and journal articles without paying additional money. Some people go to university libraries to access articles they want to read, but this is only useful if you live close to a university that has a partnership with the major publishing companies.

One other way you can access studies behind a paywall is by reaching out to researchers individually and requesting a free copy of a study. They are allowed to send published studies to individuals when contacted with a direct request for an article. You can find the author’s contact information on the article itself, but please note that this information is not always up to date as the researcher may no longer be at the indicated university. Many authors are on ResearchGate, which is a social media/networking site for researchers. You can reach out to a researcher on that site as well. One issue to be aware of is that many researchers in academia are notorious for not responding to emails/requests, so it may be useful to reach out to the other author’s listed on the paper if you do not get a timely response.

Conclusion

We hope this guide has provided you with useful information as you seek to read and interpret studies on topics that are important to you. Please remember that the scientific process means that what we understand about a topic can change with each study published. What we think is true now may be proven false as additional information comes to light. It is typically important not to come to a conclusion on a topic based on reading just one study but rather, read multiple studies (as recently completed as possible) on the topic and consider the range of findings or key learnings presented. Staying informed about a topic requires us to regularly check published studies to see what has changed and what gaps still exist in our understanding.