Chosen terminology: Throughout this toolbox we refer to “persons on the spectrum” or “Autistic persons”. We have chosen this language in agreement with recent research organization and journal guidelines. These terms encompass the previously used terms of individuals with autism, Asperger’s, and Pervasive Developmental Disorder (PDD). Activities and further reading are offered in the Appendix.

Keywords:

neurodiversity, gender diversity, LGBTQ2S+, ASD, IDD, youth, caregiver/expert, disability rights, sexuality

Glossary:

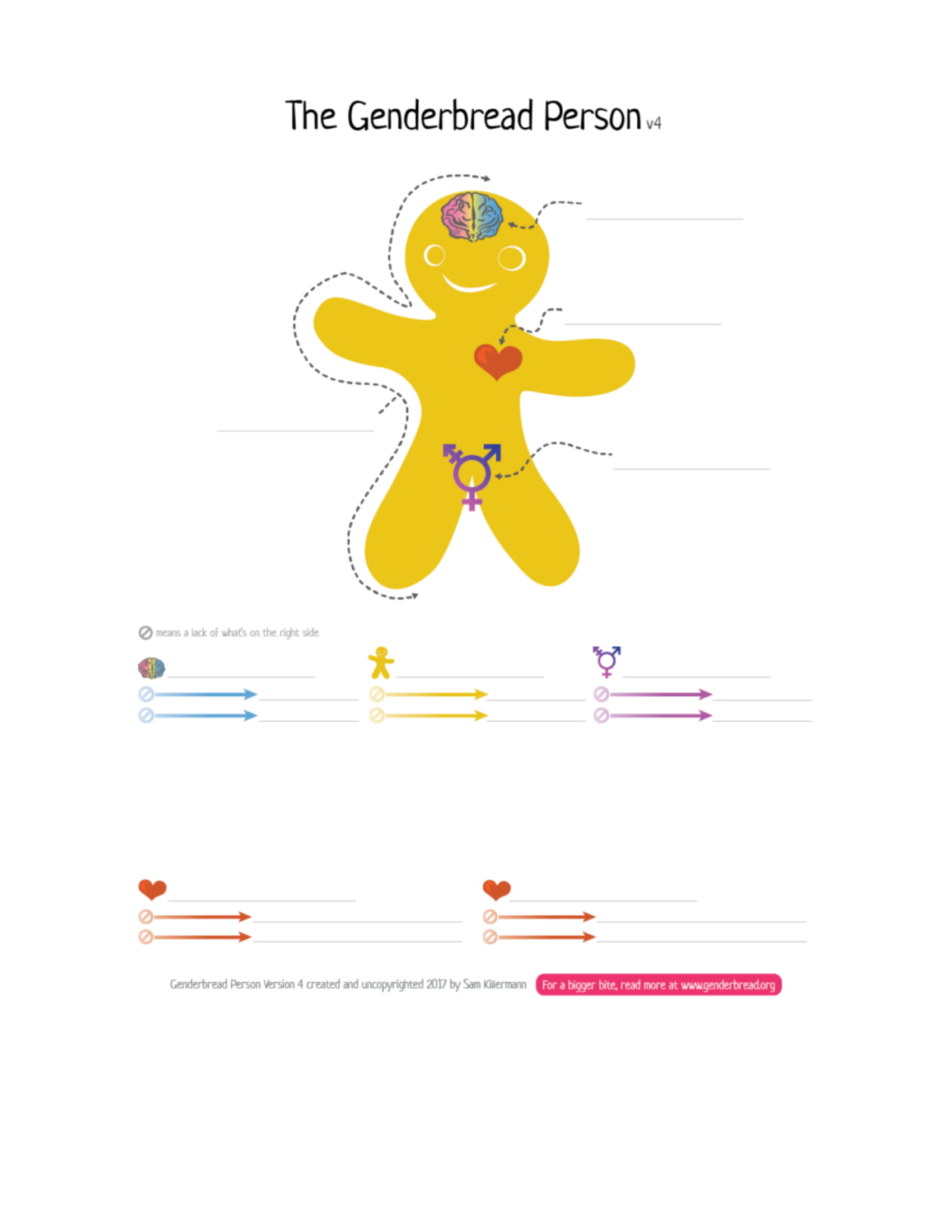

Along with “persons on the spectrum” or “autistic persons” we have also had to make choices on language on neurodiversity, gender diversity and sexuality. In this guide, we are using the term LGBTQ2S+ and member of the LGBTQ2S+ community, but also acknowledge language will continue to (and must) evolve. Currently, LGBTQ2S+ is an acronym (Figure 1) representing the terms Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans, Queer, and Two-Spirited, PLUS everything else inside and outside of what is sometimes called the ‘rainbow’ spectrum (see Figure 1).

Figure 1

Note:Break down of the LGBTQ2S+ acronym.

Some people just use LGBT whereas others prefer LGBTQ+. Many people will use an even broader collection of letters representing more terms such as LGBTTQQIAAP: Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans, Trans-gender, Transexual, Queer, Questioning, Intersex, Ally, Asexual, and Pansexual. Many advocates in Canada are putting Indigenous peoples first with by using 2SLGBTQQIA+.

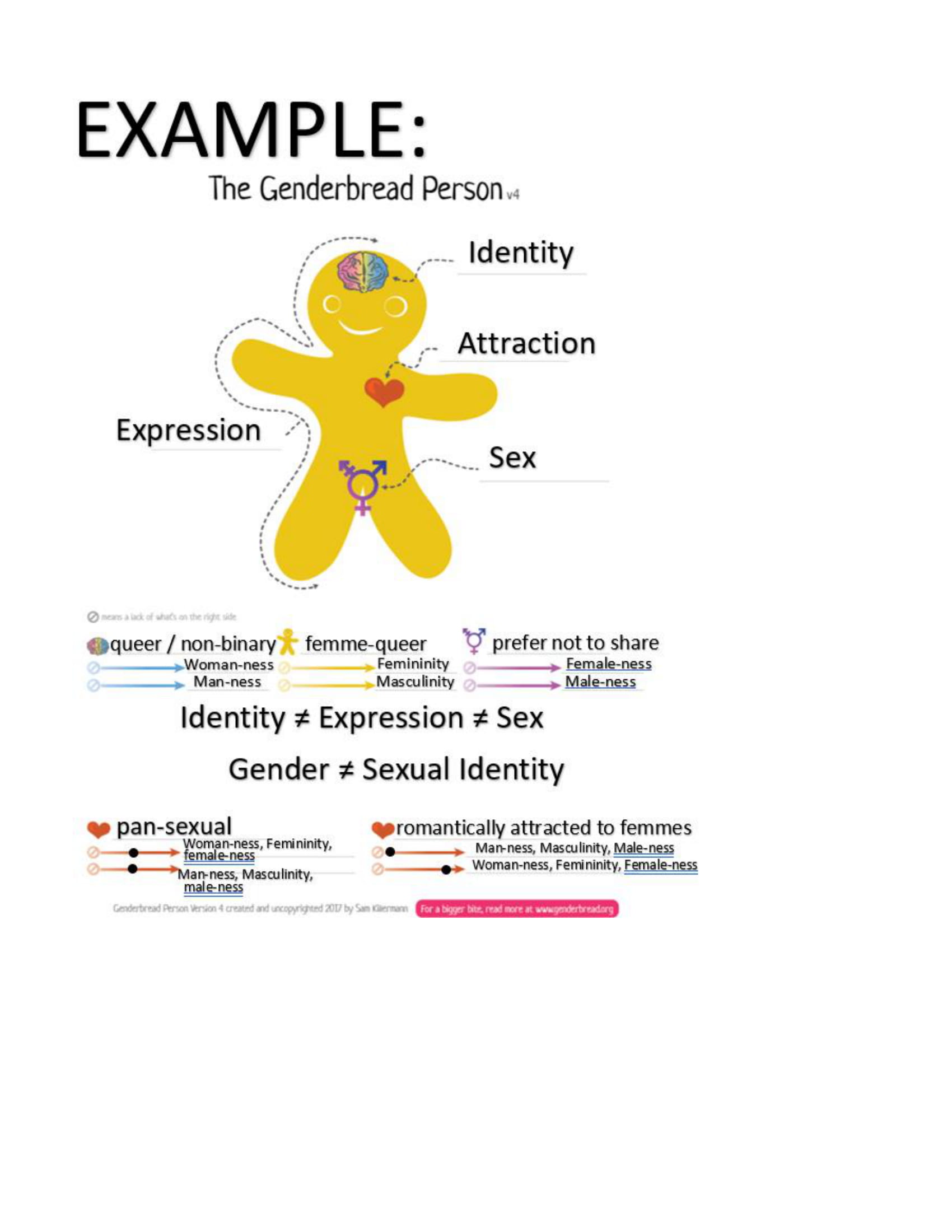

What are your definitions of the following words: gender binary, heterosexual, cisgender, gender expansive, Trans, queer, Two-Spirit, sex, and Gender Identity? For a definition of the above words, see the glossary of terminology used in this Toolkit, see Appendix A: LGBTQ2S+ Terminology, and for a quick refresher, see Figure 2.

Figure 2

| Sex Assigned at Birth | Gender |

Sex assigned at birth refers to the sexual reproductive organs a person is first born with. Female, Male, Intersex are terms used to describe sex assigned at birth.

| Gender refers to physical appearance, roles, expressions, and identities. Facebook recognizes 50+ gender identities for users to choose from (Robinson, 2014) Such as Boy, Girl, Woman, Man, Womyxm, Transgender, Gender Non-Conforming, Gender-Queer, Gender-Expansive, other. |

| Sexual Identity | Gender |

Sexual Identities are used to describe who we are romantically / sexually attracted to, and what physical and emotional traits we find attractive in others. Sexual orientation is another term some people still use.

Queer, A-sexual, A-romantic, Demisexual and more are labels used to describe a person’s sexual identity. | The roles we play out in our relationships and how we choose to physically assume, express, and identities as girl, boy, man, woman, non-binary, other, etc.

Woman, Man, Girl, Boy, Trans, Non-binary, Non-Conformative, Gender-Queer, etc. are just a few examples of gender identities. |

Note: LGBTQ2S+ Terminology differentiating gender from sexual identities and from sex assigned at birth, adapted from Appendix A.

Celebrating Neurodiversity, Gender Diversity, and the LGBTQ2S+ Community

This toolkit addresses LGBTQ2S+ awareness, visibility, and dialogue for individuals with neurodiversity and for their caregivers and families. Gender Identity, sexual freedom, and the rights of neurodiverse people are important for growing and thriving. All people have the right to self-determination meaning, in this case, the right to engage in mutual relationships that are consensual and respectful and, importantly, the right to be informed about our bodies.

John’s story:

John Cardinal has become increasingly more open about his sexual identity after having several partners. John, who is seventeen years old, recently came out to his parents about identifying on the LGBTQ2S+ spectrum despite being nervous because of his parent’s past homophobic remarks. John’s parents were originally not supportive and voiced criticism towards John’s identity and his ‘lifestyle choices.’ John has experienced years of bullying in school and has endured verbal and physical abuse from his peers. John has also experienced being bullied by a teacher and other students at school which he believes are due to developmental differences and learning challenges. He has struggled with mental health issues which he feels have been negatively influenced by the hurtful responses of others. In contrast, John’s aunt and cousin have been “a huge support because they just accept me for who I am.” He feels relieved when with them because, as he describes, “I don’t have to be someone I’m not when I’m with my aunt and cousin.”

Background Information

LGBTQ2S+ youth and adults with disabilities may face substantial challenges including judgement, stigma, and a lack of recognition for their preferences. Just like ‘coming out’ about one’s sexuality can be difficult, so too can coming out about neurodiversity. Given risk for a lack of acceptance and support, youth may experience stress and struggle with mental health when coming out. This toolkit is focused on increasing awareness related to neurodiversity and sexual identity. We hope it is a support for autistic persons, LGBTQ2S+ youth and their family, and for all folks who advocate to “uphold each person’s right to self-determination, consistent with that person’s capacity and with the rights of others” (CASW, 2005).

Sexual identity relates to those whom we find attractive and what physical and emotional traits attract us. Romantic tastes change as we age and as our preferences and priorities change. Some people, particularly youth, prefer the term romantic identities. A bi-romantic fourteen-year-old youth describes the reasoning behind their choice of language: “I think I might be bi. I like saying bi-romantic since I have only had romantic feelings but no sexual experiences yet.” Sexual orientation is a term some still use instead of sexual identity. Some individuals feel the meaning of the term orientation does not adequately reflect their experiences or their self-chosen romantic and sexual identity. Language is a choice based on one’s experiences, education, and awareness.

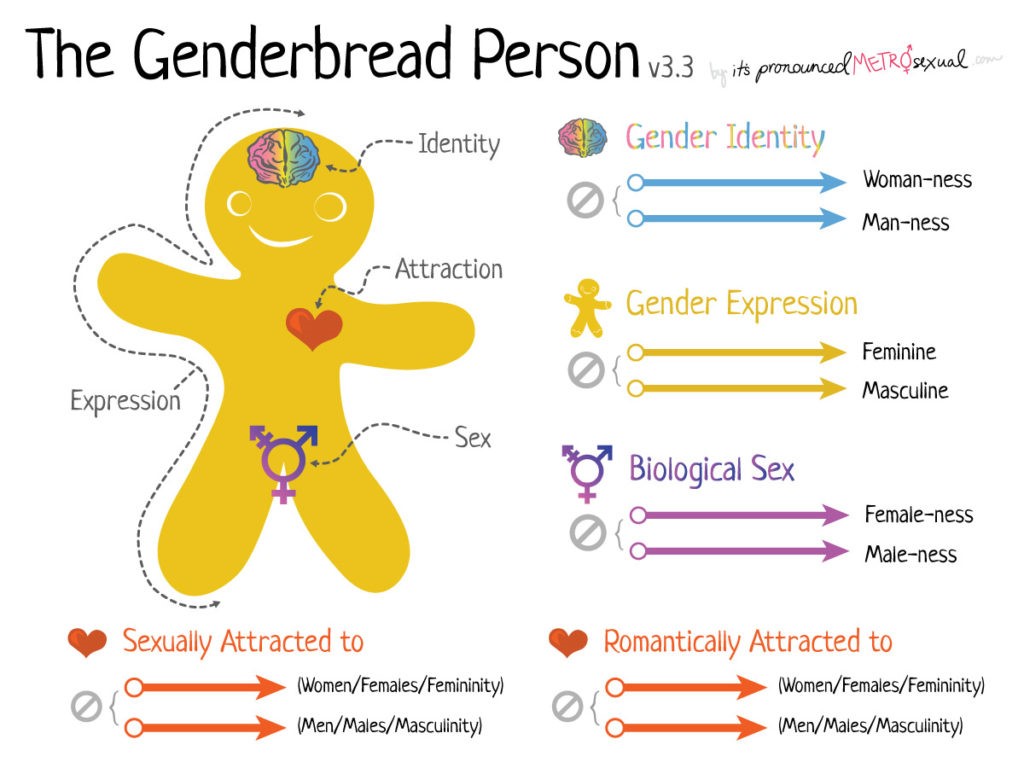

Gender identity and expression refer to how we express our femininity, masculinity, and other gender roles to the world. Sex (sex-assigned at birth and biological sex), on the other hand, refers to the medical designation of sexual and reproductive anatomy, which can be sometimes changed through treatments and surgeries. Sex is often thought of as a binary, as either male or female. Variations from female and male exist, such as intersex. Intersex reflects a person’s genetic and physical traits that are either or neither the binary female and male sexual and reproductive organs. Two percent of the world’s population are born intersex (Killermann, 2017). Definitions and attributes assigned to gender roles are different from culture to culture, and from historical era to era, and from person to person. Currently, persons who are born male, female, or intersex may identify their gender in a diversity of ways.

Generally, in western society, sexual anatomy traditionally has determined gender and roles in society. Despite western beliefs on traditional gender roles and sexual anatomy, curiosity about gender roles and gender identity is an important part of how we can understand our role in society. In many other cultures, gender expression and gender roles vastly differ from what we may have grown up with. Culture and language have an enormous impact on our understanding of gender and sexuality. Families often play a role during a child or youth’s curiosity and exploration with their gender expression. A family’s response and influence can have profound impacts on self-esteem as well as family relationships.

Training and support using LGBTQ2S-friendly resources for sexual education empower neurodiverse LGBTQ2S+ people with disabilities as well as support and provide education to family members, advocates and others. Learning and language that is sex-positive, progressive, and affirmative support individuals in exploring and expressing healthy self-identities (Bedard et al., 2010). Comprehensive sexual education for neurodiverse individuals should include considerations about the intersections of neurodiversity and gender diversity.

My Identity, My Pronouns

Your identity belongs to you. You are who you are. Gender expression is part of how we present ourselves to the world through our appearance and behaviours. Gender expression emerges through how we relate to others, including whether we express ourselves as a male, female, non-binary, non-conformative, or in other ways altogether. Gender can be experienced and expressed in many ways. One 27-year old pan-sexual girl/woman described their hair colour choice to their gender and sexual identity: “I have blue hair because I am colourful. I like being all the colours of the rainbow because I’m a queer and I’m a unicorn-- like a literal unicorn”. Many youth are challenging the traditional binaries of feminine and masculine, pink and blue.

Gender expression may be interpreted (and misinterpreted) by others, but ultimately, your gender identity is whatever you believe your gender is. Gender pronouns like ‘she’ and ‘he’ are language that people assign to us based on our gender expression, but we can also self-identify and choose our own gender pronouns that align more closely with how we perceive our own Gender Identity:

What is your Gender Identity? What are your pronouns?

Boy, Man, Trans Man, Trans He/him

Girl, Woman, Trans Woman, Trans She/her

Non-binary, Nonconforming, Queer, Trans They/their/xe/xi

Other Other

When we deny ourselves and others the right to express and celebrate who we/they are, we deny ourselves and others the right to self-determination, and dishonour the inherent dignity and worth of all persons (CASW, 2005).

What Are Your Pronouns?: How to Address Identity

People who identify or express themselves as part of the LGBTQ2S+ community usually find it polite and respectful when someone asks them “what are your pronouns?” Practice asking for a person’s pronouns! Don’t assume what they might be, just ask “what are your pronouns?” Asking a person’s pronouns is a growing trend of solidarity, particularly for members of the LGBTQ2S+ who are visibly queer, trans, gay, non-conforming, etc. LGBTQ2S+ members, particularly Trans individuals, would like this practice of asking a person’s pronouns to be universally applied to everyone.

Be cautious, however: someone who is not a member or familiar with the LGBTQ2S+ community might be confused or hostile in response to this question, especially if they hold homophobic and transphobic attitudes. Nevertheless, if more people could adopt asking about pronouns, it may open more welcoming spaces for members of the LGBTQ2s+ community. One last caution: It is important to ask yourself a few questions before choosing to ask someone else about their pronouns because your question can hurt, offend, or even humiliate another human being. Ask yourself:

- Why are you asking the question?

- Will the answer to your question change the way you feel or think about this person?

- Will this question upset the other person?

- How can you ask a question with the greatest respect?

- Are you prepared to respect the person’s answer and are you prepared to use a person’s declared pronouns?

- Are you okay with not getting an answer if they chose not to share it with you?

- Will you make an effort to correct yourself and others when a person’s gender is wrongfully assumed or mis-gendered?

- Are you prepared to respect the other person’s answer and seek to override any instinctual gendering you might do?

Activity 1: Gender Identity & Sexual Identity

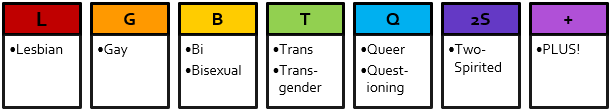

The Genderbread Person is an activity that aims to educate children, youth, and adults about our many identities including gender identity and sexuality. See Figure 3 or go to the Appendices and visit genderbread.org for more info.

Figure 3

The Genderbread Person is a great free resource, however the language it uses are “sexually attracted to” and “romantically attracted to” can be limiting since we can be sexually or romantically attracted to someone who is androgynous, or queer—not just the listed “women/females/femininity” and men/males/masculinity” that is listed.

Asking someone respectfully about their pronouns is great. However, asking someone about their sex-assigned at birth or “what are you” is rude. While many people are comfortable and “out” about their sexuality, some people have to hide their identities for fear of family rejection, negative employment impact, or fear of being discriminated against. It can be an incredibly vulnerable part of oneself to share because one may be unjustly judged, bullied and treated differently. However, sharing a vulnerable part of oneself to someone you trust and being accepted for who you are can be an important gift and act of solidarity and humanity that we can give to another person. But it is important to remember that no one owes you or other’s personal information. A person has a choice of whether or not, and if so, with whom, when, and how they disclose personal information about their sexuality.

Relationship Freedom and Sexual Safety

Sexual health is an important part of overall health, including people with developmental disabilities (Friedman & Owen, 2017). Yet, people with disabilities who also identify as LGBTQ2S+ have often reported feeling invisible (McCann et al., 2016). As noted by Hazlett et al. (2011), individuals with intellectual disabilities who are also LGBTQ2S+ have extremely limited representation in popular media, which may contribute to a lack of understanding and acceptance both by oneself and others. Another problem resulting from this invisibility includes a lack of awareness about invisible disabilities. Like many LGBTQ2S+ members who ‘come out of the closet’, neurodiverse people have the added experience of also having to ‘come out’ to people in their lives about their disability, fearing it might result in them being treated differently.

Sexual health begins with education and recognition of one’s rights and identity. To be sexually healthy, one needs to learn so that they can make informed choices. Sexual education topics include safe sex practices, healthy attitudes about how one views their body, and proper terminology. Support through positive sex education involving affirming LGBTQ2S+ language empowers and validates those who are both neurodiverse and gender diverse. It can be challenging for caregivers and experts to feel comfortable in sharing feelings and attitudes on sex, and harder still to maintain a supportive environment for youth. That said, youth are more likely to have healthy relationships based on mutuality, respect, and appropriate disclosure if these behaviours are modelled in the relationships at home. As caregivers and supporters, we need to create safe spaces for youth to explore their sexual curiosities as well as educate and create awareness about Gender Identity and sexuality. Fortunately, there are sex positive and gender-affirmative sexual education resources. See below for a few examples, or go to Appendix D: Online Resources, and explore what is available in your community:

- Alberta Health Services. (2020). Differing Abilities: Understanding Your Child’s Development. Teaching Sexual Health. https://teachingsexualhealth.ca/parents/information-by-age/differing-abilities/

- Organization for Autism Research. (2020). Sex Ed for Self-Advocates.

Https://researchautism.org/sex-ed-guide/ - First Nations Sexual Health Toolkit. (2011). Native Youth Sexual Health Network. http://www.nativeyouthsexualhealth.com/toolkit.html

- Social Skills for Sex and Intimacy. (2019). Alberta Sex Positive Education and Community Centre.

https://aspecc.ca/workshops-and-support/social-skills-for-sex-and-intimacy/

Neurodiverse, Gender-Expansive and Trans Youth

There is a common saying in the autism community that if you know one person with autism—you know one person with autism. Neurodiversity is an umbrella term for individuals whose brain functions its own way – and can include those diagnosed with a learning or developmental disability, or those who identify on the autism spectrum. Some individuals prefer the term neurodiverse.

The American Psychiatric Association (APA) uses the term “gender dysphoria” to describe people who are “uncomfortable with the gender they were assigned, sometimes described as being uncomfortable with their body (particularly developments during puberty) or being uncomfortable with the expected roles of their assigned gender” (2016). Gender-expansive is an emerging term for individuals who are gender nonconforming, particularly individuals who identify neither as a man or woman, or neither as a girl or boy. For many trans individuals, gender dysphoria is often a required diagnosis to receive some gender affirmation medical treatments.

There is a great deal of misinformation about gender dysphoria, gender reassignment, and gender affirmation. Gender affirmation could include surgeries, hormone treatment, support groups, voice therapy, gender affirming gear, legal name or gender marker change, and/or asking others to use different pronouns in referring to them. Individuals from a diversity of gender identities may choose any combination of these options.

While the impacts of multiple and “intersecting” experiences such neurodiversity, gender diversity, and sexual identities are yet unknown, “dual spectrums'' is an emerging term used to describe individuals on both the autism spectrum and the LGBTQ2S+ rainbow spectrum (Hillier et al., 2019). While there is no solid data explaining why these spectrums may overlap for some, there is speculation, and need for more research with individuals who identify as autistic and LGBTQ2S+.

In a study examining autism, Hillier and colleagues (2019) noted a lack of reliable statistics on the proportion of autistic individuals who also identify as “LGBTQ”. In another study by Stokes (2018), 70% of autistic people identified as “non-heterosexual” versus 30% of people without ASD. Increased education and research, including more awareness on gender variance and preferred terminology are required that respect individuals’ self-described identities. Emily Brooks wrote of their viewpoint in Spectrum News: “As a member of the LGBTQ community who is also autistic, I encounter inequality based on my gender identity, my sexual orientation and my disability” (2015). Brooks describes themself as being placed in a binary box as a “woman with autism” by therapists and educators despite identifying as “a non-binary queer person” (Brooks, 2015). Brooks advocates that “gender norms should not be imposed on people with autism to make the rest of the world more comfortable” (Brooks, 2015).

Dr. Wenn Lawson is an advocate and researcher on autism and gender diversity. In a video that appears on Dr. Lawson’s website entitled, “Dr Wenn Interviews Akasha 2017” (2017), gender variance and autism is discussed, suggesting “we’re not so stuck in that binary world” (11:37). Self-advocates ask important questions; for instance, Emily Brooks questions, “why teach girls with autism how to apply make-up, dress in a feminine manner and shop?”, and Brooks proposes that “therapists, educators and parents only consider these to be important goals because our society imposes strict gender norms” (see “Focus on autism must broaden to include non-binary genders” [Brooks, 2015]). Some neurodiverse individuals may be less swayed by societal expectations and perhaps are therefore more comfortable with identifying as non-binary.

Questions to Ponder:

- How important is adhering to gender norms and gender roles in your family?

- Have you witnessed or experienced homophobia, transphobia, or sexism?

- How do you feel about the interaction between neurodiversity and gender diversity?

From Where We Are to Where We Need to Be…

According to the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms “every individual is to be considered equal regardless of religion, race, national or ethnic origin, colour, sex, age or physical or mental disability” (Canadian Charter, 1982, s 6(2)[b]). As well, according to Provincial and Territorial Human Rights agencies, individuals have rights to be free from being discriminated and harassed because of their sexuality (Government of Canada, 2018). Yet like John experienced, have you experienced, or witnessed someone else experiencing, ostracism or criticism and/or being overlooked or ‘othered’ because of their body, their disability, their gender, or for who they are? Have you, or someone you love, been bullied? As illustrated by John’s experience, discrimination and oppression are absolutely wrong and can be profoundly difficult for those who experience this treatment from others.

Disability Culture is a term that Marilyn Dupré explains is a “shared experience of oppression but includes art, humour, history, evolving language and beliefs, values and strategies for surviving and thriving” (2012, p.168). Those in the LGBTQ2S+ and Disability Communities may have experienced similar patterns of being stereotyped and denied rights, but we also share stories of resiliency and celebrations of our own culture.

Some key terminology has emerged to help explain the experiences of discrimination that these communities have experienced. Ableism is the discrimination against a person because of their development, body, and/or disability. Sexism is discrimination against a person because of their gender or sex. Homophobia is discrimination against people who are Queer, Gay, Lesbian, Trans, or members of the LGBTQ2S+ community. Transphobia is discrimination against Trans people. Unfortunately, homophobia and transphobia are common within Disability Culture. Duke (2011) suggests “normalizing pressures applied by heterosexist and/or homophobic educators, caregivers, and disability service providers” (p. 37) contribute to homophobia and transphobia within Disability Culture. Likewise, the LGBTQ2S+ community has sometimes been criticized for being exclusionary to people with sensory needs due to the loud, proud nature of gatherings such as Pride Parades and the social environment of LGBTQ2S+-friendly bars or Gay-Straight-Alliances (GSA) in schools. Emily Brooks in Spectrum News wrote that “queer environments don’t often account for our sensory processing issues or social differences, whereas autism services don’t often recognize that we may identify beyond the gender binary or have queer relationships” (2015).

Figure 4

Note: Reprinted from unsplash.com “London Pride parade” (2016). CC Image courtesy of Ian Taylor @carrier_lost.

Note: Reprinted from unsplash.com “London Pride parade” (2016). CC Image courtesy of Ian Taylor @carrier_lost.

As noted earlier, LGBTQ2S+ youth and adults who experience disabilities may face even greater challenges including judgement, prejudice, and a lack of recognition of their preferences. Just like ‘coming out’ about one’s sexuality can be difficult, so too can coming out about neurodiversity. Given the risk of a lack of acceptance and support, these individuals may experience bullying, stress, and struggles with mental health when coming out. It is important that they know there are people they can talk to. Figure 5 provides some national resources, and they may be other local resources in your community.

Figure 5

Kids Help Phone Telephone (24/7): 1-800-668-6868 | Crisis Services of Canada Telephone (24/7): 1-833-456-4566 |

Youth Bullying Helpline Telephone (24/7): 1-888-456-2323 | Canadian Mental Health Association (CMHA) Find Your CMHA: |

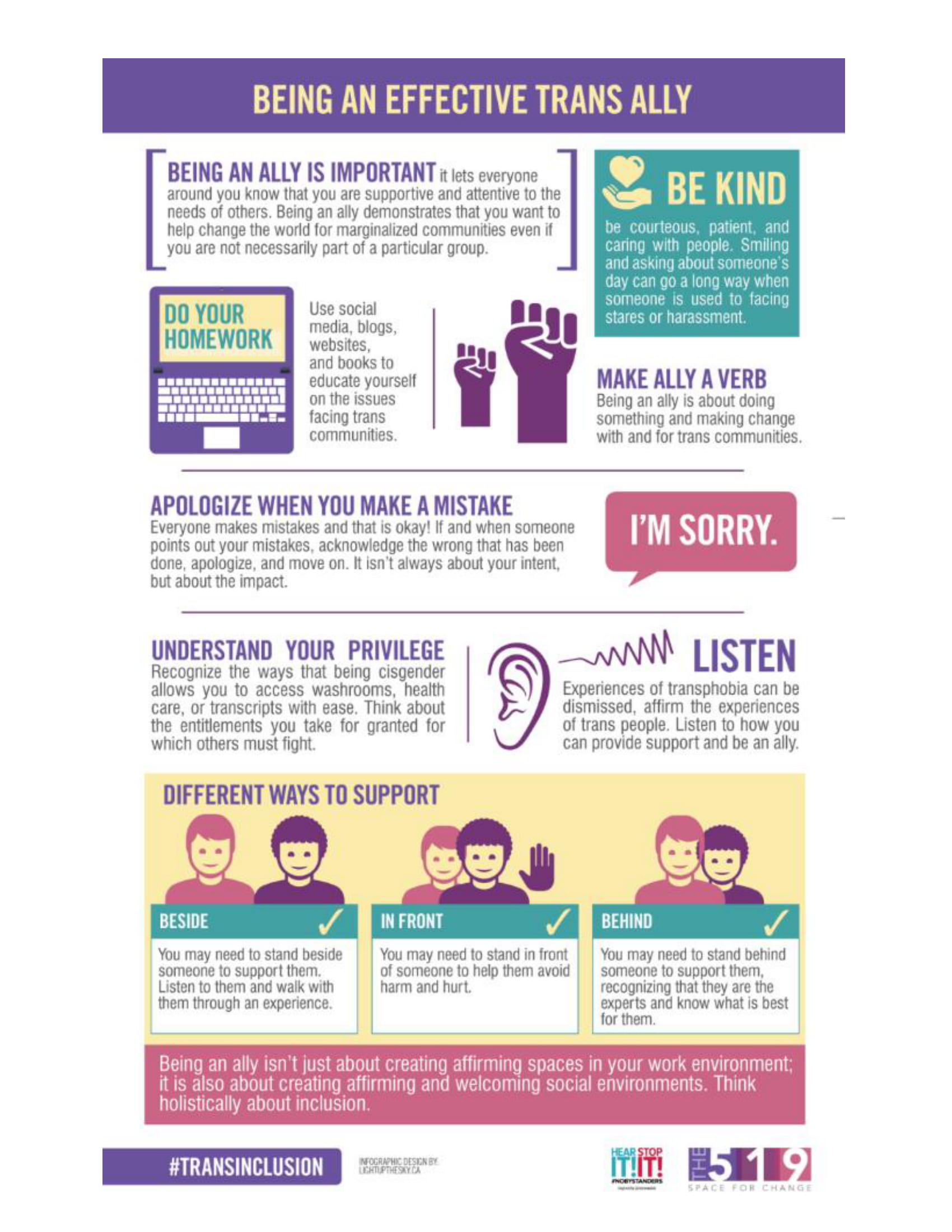

Being a Supportive Ally

Like John’s aunt and cousin, how can you support someone experiencing the effects of discrimination? You can be an ally. An ally is a person who supports an individual or group by advocating for the rights of others who are being discriminated against or treated unequally and unfairly. An allyship is a relationship of solidarity built over time. Anne Bishop is a Canadian author and community organizer who wrote Becoming an Ally: Breaking the Cycle of Oppression in People in which she defined an ally as “someone who recognizes the unearned privilege they receive from society’s patterns of injustice and takes responsibility for changing these patterns” (2002, pg.1).

According to Bishop (2002), in order to challenge oppression and be a true ally, a person must recognize and be aware of how they contribute to oppression; a true ally consistently shows up for the oppressed, not just when it is convenient. Bishop explains that allyship belongs on a spectrum from “backlasher”, to “guilty”, to “denier”, to “ally”, to “advocate” (Bishop, 2002).

Allyship begins with asking important yet tough questions: How can I help to stop the oppression of others? How can I stand up for others when they are being bullied?

Some Ways of Being an Ally

You can help create safe spaces for a friend and family member who identifies as LGBTQ2S+ to be themselves with you. Safe spaces are designated environments in which people can be free from harm and judgement. It could be a room, an office, a building, an event, etc. It could be a figurative space like an online group, online class, a website, a phone-call, or even an interpersonal relationship. Not only must safe spaces be created, so too are brave spaces needed for self-exploration and to encourage others to ask questions about their identities. Creating brave spaces is about more than just speaking out; it is about having courage to defy pressures and narrow expectations in supporting choice and decision-making about one’s own identities. Brave spaces challenge us to go beyond our comfort zones, and include safe places where we can try new things and learn from our mistakes. We need to create opportunities for vulnerability and create spaces that are open for dialogue between people of all identities and all spectrums. Practitioners, researchers, and experts in the medical community working with autistic youth should inform themselves in the latest academic research and best practices in clinical support (Strang et al., 2016). And research should be in balance with learning from the LGBTQ2s+ community including potentially making connections with pride centers in major cities, and gay-straight-alliances in schools.

In their sexual education resource (in Online Resources section), Alberta Health Services (2020) offers the following “tips for discussing sexual health” on how to “be an askable adult.” These tips include: “start early and talk often,” “keep language simple and age-appropriate,” “use proper terms for body parts and body functions,” “use teachable moments to begin the talk,” “find out what they already know,” and “talk about feelings, relationships and how they affect other people.”

Here are some other ways that you can show your bravery. This opens space for exploring and advocating for neurodiversity within the LGBTQ2S+ and neurodiversity contexts.

- Ask for consent and model consent when having discussions, ensuring there is enough time and space for discussion for all parties;

- Create dialogue whenever offensive homophobia, transphobia, or ableism occurs;

- Respect a person’s right to self-describe their own gender identity and sexual identity;

- Share resources, complete workshops and courses together, and discuss new ideas;

- Use opportunities such as new relationships, babies, and divorces to talk about sexual health and relationship freedom;

- Use movies, podcasts, and YouTube videos to explore and celebrate diversities of identities;

- Try your best to be an effective ally against oppression and discrimination;

- Commit to being a lifelong learner to understand and share awareness of Disability Culture and LGBTQ2S+ communities; and,

- Most importantly: be who you are. Celebrate others. Your identity is yours. You have the right to be yourself in all your communities. (Alberta Health Services, 2020)

Figure 5: Tips on being a useful and respectful ally.

Online Educational Resources

Sex-Ed for Self-Advocates

For Ages 15 & up

This resource was developed by the Organization for Autism Research in Arlington, VA for youth 15 years of age and older. It is a resource for self-advocates to learn about Gender Identity and sexuality. It includes audio and visual guides on “public versus private,” “puberty,” “healthy relationships,” “consent,” “dating 101,” “sexual orientation and Gender Identity,” “am I ready?,” “sexual activity,” and “online relationships and safety.” https://researchautism.org/sex-ed-guide/

Differing Abilities: Understanding Your Child’s Development (2019)

For All Ages

This resource is provided by MyHealth.Aberta.ca Network and data-sf-ec-immutable=""> for Developmental Ages Birth to 18 years of age. This online resource includes information on development at different ages, and includes helpful tools like the “Sexuality Wheel,” the “Every Body,” Understanding Consent Video, and FAQ Topic Flash Cards. For the “Sexuality Wheel” see the following page. https://teachingsexualhealth.ca/parents/information-by-age/differing-abilities

Sexual Education Resources

For Young Adults

Respectability has provided a list of comprehensive sexual education resources for young adults with developmental and intellectual disabilities. It includes links to resources for Hygiene, Self-Care, Puberty & Body Changes, Reproductive and Sexual Health, and Boundaries in Relationships, Safety Respectability.

https://www.respectability.org/resources/sexual-education-resources/

Social Skills for Sex and Intimacy

For Adults and Young-Adults

The Alberta Sex Positive Education & Community Centre offers in-person and online workshops for adults that focus on building skills like flirting, understanding consent, and building and maintaining intimate relationships. They also offer some youth specific events and are currently growing their queer youth program offerings.

https://aspecc.ca/workshops-and-support/social-skills-for-sex-and-intimacy/

First Nations Sexual Health Toolkit

For Adults and Young-Adults

The Native Youth Sexual Health Network is a resource for Indigiqueer, Two-Spirit and Indigenous LGBT+ individuals. This two-part toolkit focuses on STI, sexual health, healthy relationships and healthy body images from an Indigenous perspective. http://www.nativeyouthsexualhealth.com/toolkit.html

Visit our appendices for shareable ideas, printable worksheets, and tools.

About the Author: Jaclyn Kozak

My pronouns are they/their and my gender identity is non-binary/femme-queer with Indigenous roots. I am white passing, however, and I grew up colonized, meaning that I went without my ancestors’ Nehiyaw (Plains Cree) language and traditions. Through learning about my heritage and about Indigenous worldviews, I see gender diversity and neurodiversity as strengths with special power, rather than as a deficit, disorder, or deviance. I have a degree in drama from the University of Manitoba and I am currently a student at the University of Calgary’s Faculty of Social Work, studying from my current home in Edmonton, Alberta, on Treaty Six territory.

Acknowledgements

I would like to extend special thanks to Ryan, Cora, colleagues, friends, and my communities and families in both Edmonton and Winnipeg. My thanks also go out to librarians at both the Edmonton Public Library and the University of Calgary, as well as to the internal and external reviewers who generously reviewed and offered feedback for growth.

References

Alberta Health Services. (2020). Differing Abilities: Understanding Your Child’s Development.

https://teachingsexualhealth.ca/parents/teaching-your-child/tips-for-discussing-sexual-health/

American Psychiatric Association. (2016, February). What is Gender Dysphoria. https://www.psychiatry.org /patients-families/gender-dysphoria/what-is-gender-dysphoria

American Psychiatric Association. (2020). Autism and Autism Spectrum Disorders. https://www.apa.org/topics/autism

Bedard, C., Zhang, H., & Zucker, K. (2010). Gender identity and sexual orientation in people with developmental disabilities. Sexuality and Disability, 28, 165-175. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11195-010-9155-7

Bishop, A. (2002). Becoming an Ally: Breaking the Cycle of Oppression in People. (2nd ed.). Zed Books.

Brook, E. (2015, October 19). Focus on autism must broaden to include non-binary genders. Viewpoint, Spectrum News.

https://www.spectrumnews.org/opinion/focus-on-autism-must-broaden-to-include-non-binary-genders/

Brown, L. X. (2017). Ableist shame and disruptive bodies: Survivorship at the intersection of queer, trans, and disabled existence. In A. Johnson, J. Nelson, & E. Lund (Eds.), Religion, disability, and interpersonal violence (pp. 163-178). Springer, Cham.

Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, s 7, Part I of the Constitution Act, 1982, being Schedule B to the Canada Act 1982 (UK), 1982, c11

https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/const/page-15.html

Canadian Association of Social Workers. (2005). CASW Code of Ethics. Ottawa, ON: CASW

https://www.casw-acts.ca/files/attachements/casw_code_of_ethics_0.pdf

Duke, T.S. (2011). Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth with disabilities: A meta-synthesis. Journal of LGBT Youth, 8(1), 1-52. https://doi.org/10.1080/19361653.2011.519181

Dupré, M. (2012). Disability Culture and Cultural Competency in Social Work. Social Work Education, 31(2), 168–183.

https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2012.644945

Friedman, C., & Owen, A. (2017). Sexual health in the community: Services for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Disability and Health Journal, 10, 387-393.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1936657417300596

GLAAD. (2016). GLAAD Media Reference Guide – 10th Edition. GLAAD. https://www.glaad.org/reference

Government of Canada. (2018, September 10). Rights of LGBTI persons. Government of Canada. https://www.canada.ca/en/canadian-heritage/services/rights-lgbti-persons.html

Hazlett, L., Sweeney, W., & Reins, K. (2011). Using young adult literature featuring LGBTQ adolescents with intellectual and/or physical disabilities to strengthen classroom inclusion. Theory Into Practice, 50(3), 206-214. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/232844105_Using_Young_Adult_Literature_Featuring_LGBTQ_Adolescents_With_Intellectual_andor_Physical_Disabilities_to_Strengthen_Classroom_Inclusion

Hillier, A., Gallop, N., Mendes, E., Tellez, D., Buckingham, A.N., & OToole, D. (2019). LGBTQ+ and autism spectrum disorder: Experience and challenges. International Journal of Transgenderism. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/15532739.2019.1594484

Killermann, Sam. (2017). Genderbread Person Version 3.3. The Genderbread Person. https://www.genderbread.org/

McCann, E., Lee, R., & Brown, M. (2016). The experiences and support needs of people with intellectual disabilities who identify as LGBT: A review of the literature. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 57, 39-53. https://growkudos.com/publications/10.1016%25252Fj.ridd.2016.06.013/reader

Robinson, Amelia. (2014, February 15). Beyond male and female, definition of Facebook's new gender options. Dayton Daily News. https://www.daytondailynews.com/lifestyles/beyond-male-and-female-definition-facebook-new-gender-options/gbhsgbOMb61m5xheLPgyzL/

The 519. (2017). Being an Effective Trans Ally. The 519. https://www.the519.org/education-training/training-resources/our-resources/creating-authentic-spaces/being-an-effective-trans-ally

United Nations. (2015). Universal Declaration of Human Rights Booklet. The United Nations. https://www.un.org/en/udhrbook/pdf/udhr_booklet_en_web.pdf

Lawson, W., & Akasha. (2017, September 17). Dr Wenn Interviews Akasha 2017. Youtube. Tori Haar. https://youtu.be/RNZ_H-9zH-s

Lawson, W. (2019). Dr. Wenn B. Lawson. http://www.buildsomethingpositive.com/wenn/

Strang, F., et al. (2016). Initial Clinical Guidelines for Co-Occurring Autism Spectrum Disorder and Gender Dysphoria or Incongruence in Adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 47(1), 105–115. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2016.1228462

Winges-Yanez, N. (2014). Why all the talk about sex? An autoethnography identifying the troubling discourse of sexuality and intellectual disability. Sexuality and Disability, 32, 107-116

Appendices

Appendix A: LGBTQ2S+ Terminology

Ally: A person who supports an individual or group by advocating for the rights of others.

Asexual (ace): A person who does not experience sexual attraction or desire, but may or may engage in romantic relationships (2016). Sometimes Asexual person self-describes as an “Ace” or a-romantic (GLAAD 2016).

Bisexual / Bi: A person is who attracted to both more than one gender

Cisgender: A term used to describe someone who’s gender identity aligns with their sex-assigned at birth and who is heterosexual.

Gender binary: The normalization and belief there are only two genders of women/girls, men/boys.

Gender identity: The roles we play out in our relationships and how we choose to physically express and verbally proclaim identities as man, woman, non-binary, other, etc.

Gender expression: Refers to physical appearance, roles, and expressions as feminine, femme, masculine, androgynous, queer and/or other.

Gender dysphoria: When one feels the sex assigned at birth does not align with their gender identity and causes “conflict” (APA, 2016).

Gender expansive / gender creative / gender nonconformity: When a person’s gender identity and expression does not adhere to societal norms about gender roles and sex-assigned at birth (APA, 2016).

Heterosexual / Straight: A person whose sexual orientation is attracted to a person of the opposite sex or gender (GLAAD, 2016).

Homophobia: A person or society’s fear of someone who is not heterosexual, the fear of being LGBTQ2S+.

Homosexual: An outdated term that used to be a catch all for any sexual orientation that is not heterosexual.

Intersex: A term used to describe when a person’s genetic and physical traits are either/neither the binary female and male sexual and reproductive organs. Hermaphrodite is the older, extinct term no longer used.

Lesbian / Gay: A persons who attracted to people of the same gender or sex. A Lesbian woman is attracted to women, and a Gay man is attracted to men.

Pansexual: Pan means ‘all’, and Pansexual is someone who has the capacity to be attracted to more than one genders, like bisexual; however, there is a generational difference on how people choose to identify themselves

Sex assigned at birth: Refers to sexual reproductive organs at birth such as male, female, or intersex.

Sexism: Discrimination against a person because of their gender or sex.

Sexual orientation: Affects who we are attracted to, what physical and emotional traits we are attracted to.

Sexual Identity: A person’s choice and self-identification on their sexual orientation such as Lesbian, Gay, Pansexual, Bisexual, Asexual, Queer, Heterosexual, etc.

Trans*: The asterisk is used to indicate a “wide variety of identities under the transgender umbrella” like transgender, transitioning and/or transsexual (Glaad, 2016). It is best to ask what a person prefers. Transsexual is an older word and is presently viewed by many as offensive, but still chosen by some for self-identifying. Trans, Transgender is now the preferred term used to describe a person whose Gender Identity differs from societal norms on sex-assigned at birth and gender norms. For a more fulsome explanation, see GLAAD’s “Media Reference Guide” (2016).

Transphobia: Discrimination against Trans people.

Two-Spirit: Only Indigenous people can be Two-Spirited which refers to an Indigenous person who is LGBTQ2S+.

Queer: Sometimes used as a term to describe a person’s gender or sexual identity that is not heterosexual or cis-gendered. Some use the term “queer” as a catch-all term for the LGBTQ2S+ community. A caution though-- some older members of the LGBTQ2S+ community find this term offensive and derogatory, while younger members of LGBTQ2S+ are reclaiming the word queer (GLAAD, 2016).

Questioning: Refers to a person who is questioning their sexuality and/or Gender Identity

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2016). What is Gender Dysphoria. Retrieved from https://www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/gender-dysphoria/what-is-gender-dysphoria#:~:text=Gender%20dysphoria%3A%20A%20concept%20designated,gender%20diverse%20people%20experience%20dysphoria.

GLAAD. (2016). Glossary of Terms – Lesbian / Gay /Bisexual /Queer. GLAAD Media Reference Guide. Retrieved from https://www.glaad.org/reference/lgbtq