SUMMARY

Despite the supports that have been put in place, Canadians with developmental disabilities (DD) continue to face obstacles in gaining and maintaining employment. In 2012 two out of three Canadians with DD were out of the workforce and not looking for a job. This dismal statistic means that a large number of capable people are chronically unemployed, a situation that leads to poorer quality of life, with accompanying declines in cognitive function and general well-being.

For these neurodiverse Canadians, the cascading effects of unemployment include financial insecurity, poor self-esteem, less ability to live independently and lower community participation. For employers, it means that a pool of diverse talent and resources that would benefit their companies is untapped.

Of all disabilities, Canadians with DD face the worst employment levels. Educating employers about neurodiversity and incentivising them to make accommodations in hiring practices and in the workplace would go far toward reducing the number of jobless neurodiverse people. As a signatory to the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, Canada is expected to provide inclusive and accessible job training, education and labour market opportunities.

Yet, labour market activation programs, welfare reforms and equality laws have so far failed to make a difference in the unemployment numbers. A recent study reveals that the top three barriers to unemployment for neurodiverse Albertans include employers’ knowledge, attitude, capacity and management practices; a late start to the concept of work among people with DD; and the stigma of their disability.

Programs to remedy the situation abound at the federal and provincial levels and lately, the focus has been shifted to employer education initiatives. Much remains to be done, however, and this communiqué offers suggestions for policy changes that may benefit all parties concerned.

One policy could entail changing the design of income assistance programs like Assured Income for the Severely Handicapped (AISH) to remove disincentives to work, such as ensuring continued access to important health benefits. Governments could also offer financial incentives such as wage subsidies and tax credits to employers who hire neurodiverse people, as well as provide monetary incentives for neurodiverse Canadians who wish to be self-employed. Training programs could be available for employers to teach them the value of having a diverse workforce, as well as instructing them in how their companies can become inclusive and accessible.

Putting the proper supports in place in the early years would assist neurodiverse high-school youth to participate in career planning, work internships and job training. Helping Canada’s neurodiverse population to get and keep jobs provides benefits to the economy in terms of increased GDP, to employers in terms of talent and ability, and to people with DD who will enjoy a higher quality of life, greater self-esteem and reduced stigma and isolation.

WHY IS THIS AN IMPORTANT ISSUE?

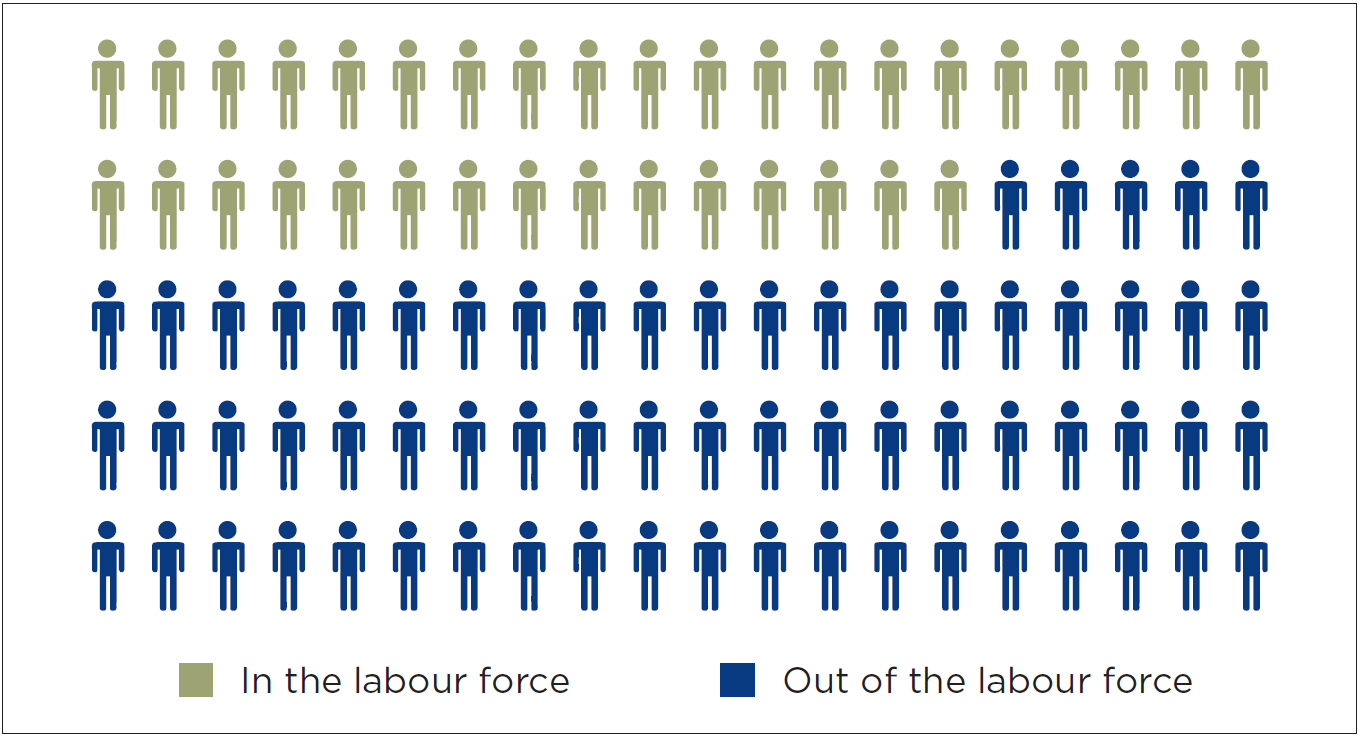

Employment outcomes for Canadians with developmental disabilities (DD) are much worse than for any other disability group. In 2012, two in three Canadians with DD were out of the labour force and not seeking work, despite this neurodiverse population having important skills to contribute to the workplace (Figure 1; Zwicker et al., 2017). Neurodiversity highlights how neurological differences like DD are the result of normal and natural variation, rather than a disease or a disorder (Jaarsma and Welin 2012).

FIGURE 1 LABOUR FORCE PARTICIPATION AMONG NEURODIVERSE CANADIANS IN 2012

Source: Zwicker et al., 2017

DD are a broad group of disabilities (such as autism spectrum disorder) that are characterized by impairments in personal, social, academic or occupational functioning. Rather than relying on clinical diagnostic criteria, this contemporary definition emphasizes the functional limitations common to neurological conditions, as well as the role of environmental factors, and aligns with the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (World Health Organization 2001). Neurodiversity acknowledges that these functional impairments need not always be “cured”, but can present opportunities for employers and society with appropriate accommodations (Austin and Pisano 2017).

Poor employment outcomes for neurodiverse Canadians have serious implications for both the affected individuals and society. Unemployment for this group is associated with poorer quality of life, lower cognitive functioning and worse overall well-being, reflecting lower financial security, independent living, community participation and self-esteem (Dudley, Nicholas, and Zwicker 2015).

Low employment rates among people with DD are also costly for society, with employers missing out on the valuable skills a neurodiverse workforce offers, and with most Canadians with DD relying on government transfers (like social assistance) as their main source of income. This is perhaps unsurprising given that the average income of a person with DD is roughly the same whether they work or rely on government transfers like social assistance – around $16,000 in 2012 (Zwicker et al., 2017).

Enhancing meaningful and sustainable employment increases economic and social inclusion, which includes being valued and welcomed by peers, expanding social networks, experiencing belonging and being able to make valued contributions to society (Canadian Association for Community Living 2011). As well, research from other countries suggests that greater participation in the workforce among the neurodiverse population increases overall GDP (PWC 2011, Buckup 2009, Metts 2000). As a signatory to the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, Canada has committed to protecting the rights and dignity of persons with DD, which means that labour markets, education and training opportunities should be inclusive and accessible.

The sizeable employment gap for the neurodiverse population has been an ongoing concern for Canada and has led to the implementation of policy initiatives such as labour market activation programs, welfare reforms and equality laws. Yet, persistently low employment rates suggest many neurodiverse Canadians continue to face serious barriers to entering the workforce and sustaining meaningful employment, while employers miss opportunities to connect with them.

INDIVIDUAL AND EXTERNAL BARRIERS TO EMPLOYMENT THAT NEURODIVERSE CANADIANS FACE

Low workforce participation among the neurodiverse population reflects a broad range of employment barriers, which have been characterized as either individual or external:

- Individual barriers are specific to the person and include relationship and social skills difficulties, as well as limited workplace readiness.

- External barriers are factors beyond the control of people with DD, such as those related to family, agencies, community and the workplace (Nicholas et al. 2018). Examples include insufficient services and resources, limited support from family and community, poor societal understanding of DD (including among employers), negative attitudes towards DD, as well as inappropriate and discriminatory hiring practices, among others.

Barriers to employment can vary among jurisdictions, depending on the policies and programs in place. Focusing on Alberta, a recent study drawing on experiences of people with DD and other stakeholders identified the top three employment barriers Albertans with DD face (Khayatzadeh-Mahani et al. 2018).[1] These include 1) employer’s knowledge, capacity, attitude and management practices; 2) late start to the concept of work and workplace culture education; and 3) stigma (Box 1).

| Box 1 Comments from study participants “ An employer who doesn’t know how to hire someone with autism, or how to interact with them, or how to handle their daily issues or how to accommodate them without being disrespectful, prefers to avoid these issues…” “ … they [persons with DD] start too late to enter the job market and they receive limited information about workplace culture at high school; so you can’t expect them to have enough work experiences.” |

Identifying these barriers and how they interact with one another is critical to assessing the effectiveness of existing policies as well as designing new policy.

WHAT IS CURRENTLY BEING DONE IN ALBERTA TO ADDRESS THESE BARRIERS AND IMPROVE EMPLOYMENT OUTCOMES?

Many organizations, services and programs in Alberta are working to improve employment outcomes for the neurodiverse population. There are programs and policies at both the federal and provincial level that provide education, training, counselling, job assistance services, skills development and targeted wage subsidies to advance an individual’s position in the labour market – whether they are employed or not (see Table 1). Employer-focused opportunities such as the Canada Job Fund or the Opportunities Fund for Persons with Disabilities suggest government is shifting focus from employees/individuals with DD to the creation of inclusive and supportive workplaces.

TABLE 1 LEGISLATION AND EMPLOYMENT SUPPORTS AVAILABLE FOR NEURODIVERSE ALBERTANS WITH QUALIFYING DISABILITIES

| Federal Government | Government of Alberta | |

|---|---|---|

| International agreements | • United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities | |

| Legislation | • Canadian Human Rights Act • Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms • Employment Equity Act • Federal accessibility legislation – in drafting phase | • Alberta Human Rights Act • Premier’s Council on the Status of Persons with Disabilities Act • Persons with Developmental Disabilities Services Act • Income and Employment Supports Act • The Fair and Family-Friendly Workplaces Act |

| Programs & Supports | • Opportunities Fund for Persons with Disabilities • Canada-Alberta Labour Market Agreement for Persons with Disabilities funding under Labour Market Agreements for Persons with Disabilities (LMAPDs) • Western Economic Diversification Canada Entrepreneurs with Disabilities Program • Canada Pension Plan (CPP) Disability – Disability Vocational Rehabilitation Program • Employment Insurance – Employment-Related Services • Aboriginal Skills and Employment Training Strategy – Disability Services • Working Income Tax Benefit Disability Supplement (and Disability Tax Credit) • Disability-Related Employment Benefits • Disability Supports Deduction • Refundable Medical Expense Supplement | • Alberta Works (including Employment and Training Services and Transition to Employment Services) • Assured Income for the Severely Handicapped (AISH) • Persons with Developmental Disabilities (PDD) – Program Employment Supports and Community Access Supports • Disability-Related Employment Supports (DRES) |

Yet, in spite of the suite of legislation, policies and programs designed to boost employment among Albertans with disabilities, low workforce participation among neurodiverse Albertans indicates that existing supports are either not effective and/or sufficient.

SOLUTIONS TO PRIORITIZED BARRIERS AND POTENTIAL POLICY TOOLS TO IMPLEMENT SOLUTIONS

Participants in the previously mentioned study also identified policy solutions to address the prioritized barriers: i) changing Assured Income for the Severely Handicapped (AISH – Alberta’s disability social assistance) to remove barriers and disincentive to work; ii) increasing employment opportunities; iii) promoting employer training and knowledge, with education on inclusion, acceptance and human difference to be taught early on in both school and the workplace; iv) promoting better education (building employability and job skills into education) in high school to enable smooth transition to post-secondary or employment (Khayatzadeh- Mahani et al. 2018).

Below we outline some suggested policy tools, albeit not exhaustive, that could be considered to implement the proposed solutions (Table 2). Each tool is accompanied by advantages and disadvantages that should be carefully considered within the context of the policy environment within which it is being implemented.

TABLE 2 POSSIBLE POLICY ACTIONS

| Proposed policy solution | Possible policy actions to implement solution |

|---|---|

| Remove barriers and disincentive to work in AISH | • Design appropriate earning exemptions (and indexed to inflation) • Develop working credits or annualise earning exemptions to ensure people working irregular hours from week to week are not penalised • Ensure unlimited reinstatements and rapid requalification for disability social assistance if employment is lost • Ensure continued access to the same level of extended health benefits after employment is secured • Provide employment entry payment/start-up benefit • Provide employment transportation allowance |

| Increase employment opportunities | • Renew Alberta’s vision and employment strategy for persons with DD • Incentivize employers to hire people with disabilities (for example, financial incentives such as wage subsidies, workplace tax credits or funding support for accommodations, assisted access to community-based expertise about accommodation and return-to-work, and grants to retain, hire or retrain employees with disabilities) • Provide support and incentives for self-employment for people with DD • Incentivize the review and reform of recruitment and management practices for people with DD in the workplace and identify best practices in collaboration with employer and employee associations |

| Promote employer training and knowledge | • Incentivize the development of diversity policies and train and educate staff to understand the benefits and business case of a diverse workforce • Establish a centre of expertise to help disseminate information to employers on their respective duties, potential best practices and available resources to draw on when recruiting and working with employees with DD, as well as when a worker experiences a health shock and may require a leave from or accommodation to their work • Work with networks such as Canadian Business SenseAbility and Ready Willing and Able to share knowledge about accessible and inclusive workplaces • Expand curriculum on disability, access, inclusion and equality throughout education |

| Promote better education in high school to enable smooth transition to post-secondary or employment | • Ensure access to appropriate learning supports and services in elementary and secondary education • Develop and provide high school students with structured intern work opportunities, career-planning activities and training services such as employment readiness programs like Worktopia • Improve transition planning for youth with DD and work placements • Expand post-secondary education • Expand government accommodation grants • Fund direct services and on-site supports for post-secondary students with disabilities • Increase college-based adult special education programs |

Sources: (Fredeen et al. 2013, Cohen et al. 2008, Prince 2016, Meredith and Chia 2015)

REFERENCES

Austin, Robert D, and Gary P Pisano. 2017. “Neurodiversity as a Competitive Advantage.” Harvard Business Review:1-9.

Buckup, Sebastian. 2009. The price of exclusion: the economic consequences of excluding people with disabilities from the world of work. International Labour Organization.

Canadian Association for Community Living. 2011. Achieving social and economic inclusion: from segregation to ‘employment first’. In Law Reform and Policy Series.

Cohen, Marcy, Michael Goldberg, Nick Istvanffy, and Tim Stainton. 2008. Removing Barriers to Work. Flexible Employment Options for People with Disability in BC. edited by Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives.

Dudley, Carolyn, David B Nicholas, and Jennifer Zwicker. 2015. “What do we know about improving employment outcomes for individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder?”.

Fredeen, Kenneth J, K Martin, G Birch, and M Wafer. 2013. “Rethinking disability in the private sector.” Panel on Labour Market Opportunities for Persons with Disabilities 28.

Jaarsma, Pier, and Stellan Welin. 2012. “Autism as a natural human variation: Reflections on the claims of the neurodiversity movement.” Health Care Analysis 20 (1):20-30.

Khayatzadeh-Mahani, Akram, Krystle Wittevrongel, David B Nicholas, and Jennifer Zwicker. 2018. “Prioritising barriers and solutions to improve employment for persons with developmental disabilities.” (in press).

Meredith, Tyler, and Colin Chia. 2015. Leaving Some Behind: What Happens When Workers Get Sick: Institute for Research on Public Policy= Institut de recherche en politiques publiques.

Metts, Robert L. 2000. “Disability issues, trends, and recommendations for the World Bank (full text and annexes).” Washington, World Bank.

Nicholas, David B, Wendy Mitchell, Carolyn Dudley, Margaret Clarke, and Rosslynn Zulla. 2018. “An Ecosystem Approach to Employment and Autism Spectrum Disorder.” Journal of autism and developmental disorders 48 (1):264-275.

Prince, Michael J. 2016. “Inclusive Employment for Canadians with Disabilities: Toward a New Policy Framework and Agenda.” IRPP Study (60):1.

PWC. 2011. Disability Expectations. Investing in a better life, a stronger Australia.

World Health Organization. 2001. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health: ICF: World Health Organization.

About the Authors

Stephanie Dunn is a Research Associate in the Health Policy team at The School of Public Policy at the University of Calgary. Her research interests include disability, health and social policy.

Krystle Wittevrongel is a Research Associate in the Health Policy team at The School of Public Policy at the University of Calgary. Her research interests include health and social policy and the utilization of policy to better support vulnerable populations.

Jennifer Zwicker is the Director of Health Policy at The School of Public Policy and an assistant professor in the Faculty of Kinesiology, University of Calgary. With broad interests in the impact of health and social policy on health outcomes, Dr. Zwicker’s recent research utilizes economic evaluation and policy analysis to assess interventions and inform policy around allocation of funding, services and supports for children and youth with developmental disabilities and their families. This work is supported by the Kids Brain Health Network, the Sinneave Family Foundation and the CIHR funded Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research network on childhood disability called CHILD-BRIGHT.

ABOUT THE SCHOOL OF PUBLIC POLICY

The School of Public Policy has become the flagship school of its kind in Canada by providing a practical, global and focused perspective on public policy analysis and practice in areas of energy and environmental policy, international policy and economic and social policy that is unique in Canada. The mission of The School of Public Policy is to strengthen Canada’s public service, institutions and economic performance for the betterment of our families, communities and country. We do this by:

• Building capacity in Government through the formal training of public servants in degree and non-degree programs, giving the people charged with making public policy work for Canada the hands-on expertise to represent our vital interests both here and abroad;

• Improving Public Policy Discourse outside Government through executive and strategic assessment programs, building a stronger understanding of what makes public policy work for those outside of the public sector and helps everyday Canadians make informed decisions on the politics that will shape their futures;

• Providing a Global Perspective on Public Policy Research through international collaborations, education, and community outreach programs, bringing global best practices to bear on Canadian public policy, resulting in decisions that benefit all people for the long term, not a few people for the short term.

The School of Public Policy relies on industry experts and practitioners, as well as academics, to conduct research in their areas of expertise. Using experts and practitioners is what makes our research especially relevant and applicable. Authors may produce research in an area which they have a personal or professional stake. That is why The School subjects all Research Papers to a double anonymous peer review. Then, once reviewers comments have been reflected, the work is reviewed again by one of our Scientific Directors to ensure the accuracy and validity of analysis and data.

The School of Public Policy University of Calgary, Downtown Campus 906 8th Avenue S.W., 5th Floor Calgary, Alberta T2P 1H9 Phone: 403 210 3802

DISTRIBUTION

Our publications are available online at www.policyschool.ca.

DISCLAIMER

The opinions expressed in these publications are the authors' alone and therefore do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the supporters, staff, or boards of The School of Public Policy.

COPYRIGHT

Copyright © Dunn, Wittevrongel and Zwicker 2018. This is an open-access paper distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons license CC BY-NC 4.0, which allows non-commercial sharing and redistribution so long as the original author and publisher are credited.

ISSN

ISSN 2560-8312 The School of Public Policy Publications (Print) ISSN 2560-8320 The School of Public Policy Publications (Online)

DATE OF ISSUE

June 2018

MEDIA INQUIRIES AND INFORMATION

For media inquiries, please contact Morten Paulsen at 403-220-2540. Our web site, www.policyschool.ca, contains more information about The School's events, publications, and staff.

DEVELOPMENT

For information about contributing to The School of Public Policy, please contact Sharon deBoer-Fyie by telephone at 403-220-4624 or by e-mail at sharon.deboerfyie@ucalgary.ca.

Reproduced with the permission of Dr. Jennifer Zwicker (School of Public Policy, University of Calgary). This information appeared originally at https://www.policyschool.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Employment-Outcomes-Dunn-Wittevrongel-Zwicker-final2.pdf.

[1] † We acknowledge the support of the Sinneave Family Foundation.

[2] In 2017, the University of Calgary’s School of Public Policy held a one-day stakeholder event to identify barriers to

employment for persons with DD and to brainstorm policy solutions that may help overcome those challenges. Participants in the event included people with DD, family members and caregivers, employers, vocational training professionals, nonprofit organizations and decision- and policy-makers. The nominal group technique (NGT) and the Delphi technique were used as formal consensus development models among participants.

Photo by Evangeline Shaw on Unsplash