Supporting Individuals with Limited Speech

By Pat Mirenda, Ph.D., BCBA-D

Stephanie is a 10-year-old girl who has autism and limited speech. However, she is a successful communicator both at school and at home. When she wants something within her visual range, she leads a family member, classmate, or teacher to it and vocalizes. When she wants something that is out of sight or in another location, she points to pictorial symbols on an iPad, using a communication application (“app”). She also uses the app to participate in classroom activities; for example, when her class learned about volcanoes last month, she was able to answer questions such as “What do we call the melted rock that comes from a volcano?” To see what is happening each day, Steph uses a different app with a visual schedule. During recess and lunchtime, she and her friends enjoy looking through her conversation book, in which there are pictures of Steph, her family, and her friends doing fun activities (like going to Playland last summer).

During writing and math activities in her classroom, Stephanie uses a computer with adapted software with spelling support. She also uses a computer at home to play games with her brother and her dad. Last but certainly not least, Steph uses her speech to greet people, ask for help, answer “yes” and “no questions, and say “stop” when she doesn’t like what is happening.

Stephanie is a very fortunate child! It is clear that she has been supported by family members and school personnel who understand that her difficulty with speech doesn’t mean she has nothing to say, and who have made systematic efforts to provide her with an individualized augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) system. Just like you and I, Steph communicates in a variety of ways, depending on the situation. One AAC technique will never meet all of a person’s communication needs, so a combination of approaches will always be needed. In this chapter, the combination of all of the symbols and devices used by an individual is referred to as his or her AAC system.

What Is AAC?

Communication is a human right. Everyone can communicate, and everyone deserves to have a way to do so. Augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) refers to interventions designed to compensate for an individual’s communication difficulty. For people who are unable to speak at all, AAC serves as an alternative to speech. More often, AAC is used to augment speech, as most people are able to say at least a few words. When speech is quite effortful to produce and/or is difficult for others to understand, an AAC system is required. In specific circumstances, AAC can also be useful for people with fluent speech; for example, when Jeremy has to give a presentation to his college class, he types it in advance, stores it on his laptop, and then uses the voice output function to speak it out loud. Jeremy prefers to do this in order to reduce presentation anxiety while fulfilling the course requirement. Speaking individuals who tend to repeat previously-heard words and phrases (often called echolalia) can also benefit from AAC, which enables them to communicate more fluently.

Damon Kirsebom is a young man who lives in British Columbia. He is able to speak but prefers to communicate by typing on an iPad. In this video, Damon talks about his experience as a person who relies on AAC: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ORwKS802gTM

AAC Myths

Before we explore AAC systems in more detail, we need to deal with a few of the most prevalent AAC myths. It is important to address these, as these myths result in misunderstandings that can have a negative impact on the outcome of an AAC intervention.

Myth #1: AAC = Technology

Many people think that AAC requires some type of digital technology that produces spoken output -- most often, an iPad with a communication app. While it is true that voice output technology can be useful, it is rarely appropriate as the sole component of an AAC system, and some individuals do not need technology at all. Decisions about when and how to use technology as part of an AAC system are complex and often requires input from a multidisciplinary team that includes family members and professionals who are familiar with the wide range of AAC options, such as speech- language pathologists and AAC specialists. Simply purchasing an iPad and an AAC app that was recommended by someone on Facebook is unlikely to result in long term communication success!

Myth #2: AAC will inhibit speech development

This is one of the most common myths about AAC, and is of particular concern to parents of young children. However, there is ample evidence that AAC techniques do not interfere with the development of speech--in fact, AAC may promote speech development. A number of research studies have investigated this issue in children with autism. For example, one study found that, of 72 children who were taught to use manual signs, none showed a decrease in speech production, and many children with good verbal imitation skills had improved speech after manual signs were introduced (Millar et al., 2006). These researchers also reviewed 10 studies where AAC intervention involved the use of picture-based AAC systems such as the Picture Exchange Communication System (PECS). All 167 children involved in these studies showed improvements in either verbal approximations or speech production. Finally, the authors reviewed two studies where the AAC intervention involved the use of speech generating devices (i.e., computerized devices where an individual presses one or more buttons and a message is ‘spoken’ out loud). All nine of the children involved demonstrated improvements in speech production. Overall, it seems clear that AAC does not interfere with speech development and, for some individuals, can support speech production.

In addition, it is clear that a ‘wait and see if speech develops’ approach can be detrimental. Withholding AAC intervention while waiting for the possibility of speech to develop may result instead in the development of problems such as challenging behavior as well as a loss of social and learning opportunities. Based on current information, it is better to introduce AAC early in a child’s development; this will help the child to communicate with greater ease, thereby reducing frustration. Some children may develop sufficient speech and no longer require AAC, many may continue to use AAC along with speech, while some may rely on AAC as their primary means of communication throughout the lifespan.

Myth #3: AAC should be introduced gradually

It is not unusual to see a pictorial AAC display that contains only a few symbols that represent basic messages – often, words like cookie, juice, more, play, toilet or bathroom, and finished. Imagine what it would be like for you if your entire vocabulary consisted of these six words! How often would you have an opportunity to communicate? How motivated would you be? Instead, it is important to provide AAC vocabulary in activities that occur throughout the day, in many contexts and for many purposes. Later in this lesson, we will discuss some of the ways this can occur but for now – gradual is not better!

Myth #4: “He/She is too old to benefit from AAC”

Of course, introducing AAC when a person is young is preferable, but it is a myth to believe that age is a limiting factor. If you viewed Damon’s video previously, you have already seen evidence of this, as he was not provided with access to an AAC system until he was 14 years old. It is never too late to provide AAC for the first time, or to try a new AAC approach if previous attempts have failed. In fact, if we believe that all people can communicate, there is no reason to stop exploring AAC options, until a successful solution is found.

A video featuring Carr, an 8-year-old with Down syndrome, illustrates the point that it is "never too late" to introduce AAC (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IGKS95G4ynM). Please skip the ad after 5 seconds to view the video.

AAC Approaches

In its most basic form, AAC requires symbols that represent words or messages and a way to access them. Let’s start with the latter; most people who use AAC techniques are able to use their hands/fingers to make a manual sign or point to/select a symbol from a display of options. But this is not always the case; for example, people with motor impairments that affect the upper extremities will need a different way to access communication symbols. Many alternative access techniques are available, including eye gaze/eye tracking, use of a head mouse, single or dual switch scanning, and other specialized options. Unfortunately, it is beyond the scope of this introductory module to explore these techniques in any detail. If alternative access is needed, an occupational and/or physiotherapist with expertise in AAC should be consulted to determine how to best accomplish this.

Ava is a 7-year-old girl with Rett syndrome, which prevents her from using her hands and arms in functional manner. She communicates using a digital AAC device with eye tracking for alternative access. You can read her story and view a video of Ava with her family at this website: https://us.tobiidynavox.com/pages/rett-syndrome-success-story-ava

AAC Symbols and Approaches

A symbol is something that stands for something else (often called the referent). Communicating without speech requires the use of symbols that can be used to construct messages. There are two main types of AAC symbols: unaided and aided. Unaided symbols do not require any equipment to produce, and include gestures, body language, and manual signs. Aided symbols require devices that are external to the individuals who use them, such as communication books and speech generating devices (SGDs) such as an iPad with a communication app. In this section, we will review the most commonly used AAC approaches (both unaided and aided) and discuss some of the primary advantages and disadvantages of each.

Unaided Approaches

Gestures and body language. Before children learn to speak, they use a wide variety of gestures to communicate. Some of these gestures appear to be natural extensions of other actions; for example, pointing is very similar in form to reaching for something. Others seem to develop as an extension or a pantomime of actions; for example, a child may hold out her arms in the direction of an adult to ask for a hug. Still other gestures have meanings only within a given culture, such as the “thumbs up” gesture often used in North America to indicate approval or agreement. Although many gestures involve hand motions, we also use other parts of our bodies to convey messages. We shrug our shoulders to indicate doubt, we frown when we disagree, and we nod or shake our heads to mean, “yes” or “no.”

People use gestures to communicate many types of messages. Perhaps the most obvious is communication about wants and needs. For example, we may hold out two toys to a child, saying, “Which one do you want to play with?” When the child points to or simply takes the desired toy, the child communicates with us. Similarly, before they are two years old, most children learn that they can get help from adults by simply bringing objects to them. They also learn that they can get people to look at objects or events of interest by pointing to them; the child’s pointing gesture means, “Do you see what I see?” Other gestures, such as waving “hi” or “bye-bye,” blowing a kiss, and playing peek-a-boo, are used for purely social reasons. These gestures tell us that the child enjoys our company, and they are extremely important in developing smooth social interactions between friends or between children and adults.

A common mistake in teaching communication skills is neglecting the importance of natural gestures as components of a communication system. This mistake often occurs because many parents and teachers tend to view communication as an “either-or” skill: either the person communicates this way or the person communicates that way -- which, of course, is not the case! It is important to respond to and encourage individuals to use all forms of communication, so long as those forms are understandable and socially acceptable. For example, when Joshua leads his father to the cupboard to ask for a treat, or when Juanita cries after she falls down and skins her knee, they are communicating messages (“I want something” and “Ow! That hurt!”) that should be respected and acknowledged.

Manual signs.

You are probably familiar with the language systems of manual signs used by people who are Deaf. Some individuals who are able to hear but have difficulty understanding and/or producing speech may

also use manual signs for both expressing and understanding language. Manual sign input occurs when people who communicate to a person use signs to augment their speech. For example, Felicia’s teacher speaks while signing the key words

in her message. So, when it is time to do math, she tells Felicia to “Get out your book and a pencil” while signing get, book, and pencil. She does this because Felicia seems to pay attention more readily and follow directions

more accurately if she is provided with signed information in addition to speech. Manual sign output occurs when someone uses manual signs to communicate to others. For example, when Felicia can’t find her math book, she asks her teacher

to assistance by signing “help, please.”

One advantage of manual signs is that they are totally portable (you will never leave your hands at home by mistake!) and require no external equipment. On the other hand, most parents, teachers, and classmates do not understand manual signs, and some individuals do not have the manual skill (i.e., finger dexterity) that is needed to produce them accurately. Decisions about whether or not to incorporate manual signs in a person’s communication system should be made in consultation with the team of professionals who provide support. Factors to be considered include:

- Whether a person can learn signs via imitation or physical prompting (research shows that a least one of these is needed),

- The person’s fine motor skills/finger dexterity skills,

- How many people in the person’s life are willing and able to learn manual signs and use them regularly,

- The likelihood that the signs will be understood by familiar and unfamiliar partners at school, home, and in the community; and

- How rapidly the person will be able to learn new vocabulary words in sign language vs. in other modalities.

Aided Symbols

Object-based systems. The easiest type of aided symbol for most people to learn is a real object symbol, a three-dimensional object (or partial object) that stands for an activity, place, or thing. For example, Marcia uses real object symbols to ask for what she wants and to share information with others. If she's thirsty, she brings her teacher a cup to ask for something to drink. If she wants to go out in the car, she brings her mom the car keys. After she goes to the park, she can tell her sister what she did by showing her the Frisbee that she enjoyed using there. For Marcia, the cup, keys, and Frisbee are symbols representing "I'm thirsty," " I want to go out in the car," and "I went to the park." These specific symbols were selected for Marcia because she always drinks from a cup, sees her mom use those keys, and carries the Frisbee to the park. She has learned from experience to associate the symbols with the activities they represent. At school, Marcia also uses a real object schedule that helps her understand what will happen next in the school day (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Marcia’s object schedule at school, representing (left to right) circle time, choice time, arts and crafts, snack, recess, lunch, a special activity, and getting ready to go home. Line drawing symbols are paired with the objects so Marcia can learn what they mean.

“Low tech”/nondigital symbol systems. As noted previously, one of the biggest myths about AAC is that AAC requires the use of digital technology – an iPad, a dedicated speech-generating device, or a computer. Wrong! In fact, “low tech”/non-digital AAC techniques can be used to meet the needs of many individuals, either alone or in combination with digital approaches. We all use nondigital AAC approaches regularly, although we probably don't realize it! Do you keep track of upcoming appointments using a paper-based calendar? Do you use a handwritten grocery list when you shop? Have you ever shared family photographs in your wallet with co-workers or neighbors, or pointed to a picture in a menu to order your food in a restaurant? All of these are examples of nondigital AAC techniques – they use various types of symbols to represent messages, but they are not housed on a smart phone, tablet, or computer. Additional examples include:

- A communication book that contains printed, laminated symbols. A person can point to one or more symbols to communicate a message or can compose as message using a series of symbols on a message strip. The Picture Exchange Communication System (PECS) is the most well-known example of this type of system (Frost & Bondy, 2002);

- A communication board, wallet, or keychain on which symbols are either printed or affixed with Velcro;

- Another device that is neither battery-operated nor computer-based, such as a date book or notepad.

In this video, 3-year-old Rage uses a nondigital PECS book to ask for body parts (to complete Mr. Potato Head), colours, and animals: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WPRrMorSAkQ

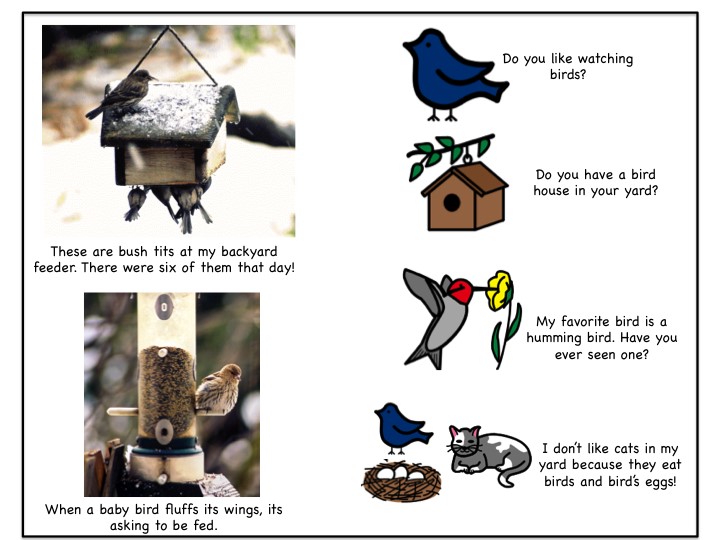

Many types of symbols can be used to represent messages in a nondigital AAC system. Photographs can be used to represent specific people, places, activities, or items; these days, virtually everyone has access to a smart phone that can be used to take good quality photos that can be printed with ease. For example, Hoa uses photos of food items to ask for her lunch in the workplace cafeteria. She shares information about her family by using photos of them, and she can tell her housemates about her trip to San Diego last summer by showing them postcards and photos of the places she visited. Fatemeh, age 15, uses a combination of photographs and coloured line drawing symbols in her nondigital conversation book to tell her friends about the birds in her backyard (Figure 2). Her friends are able to read, so the picture captions enable her to share information and ask questions during this social interaction.

Figure 2: Images in Fatemeh’s conversation book about birds in her backyard.

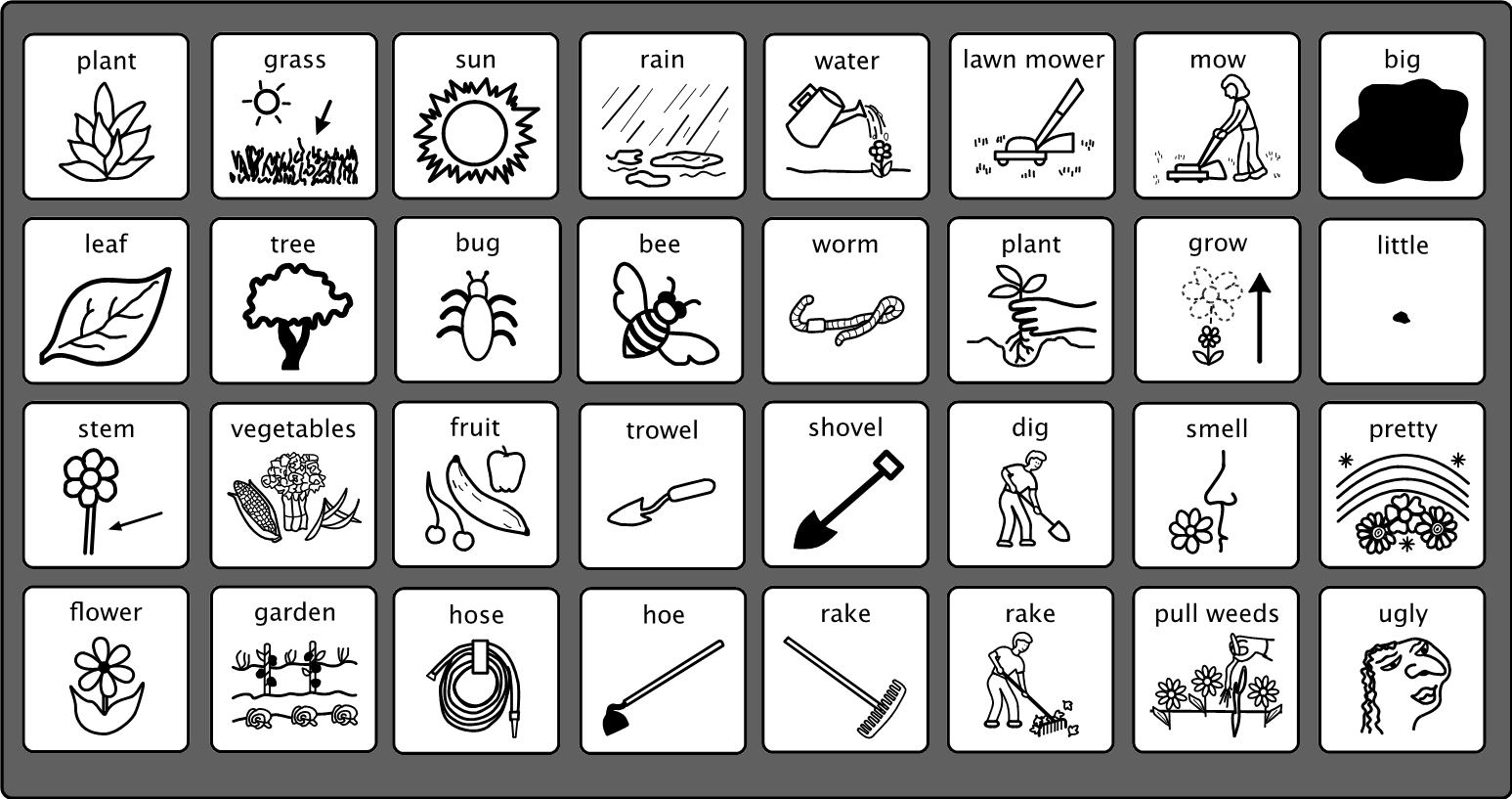

Another option involves line drawing symbols -- black and white or colour illustrations that represent people, places, activities, and items, as well as actions (eat, sit, sleep, etc.), feelings (happy, angry, bored, etc.), descriptors (hot, little, up/down, etc.), and social etiquette messages (please, thank you, etc.). Many types of line drawing symbol sets are commercially available in a variety of sizes and forms (including some that permit a printed word in one or two languages to accompany the symbol) from different companies. The symbols can be printed and laminated for inclusion in a communication book, board, or wallet.

Two of the most commonly-used line drawing symbol sets in North America are Picture Communication Symbols (https://goboardmaker.com/pages/picture-communication-symbols) and SymbolStix (https://www.n2y.com/symbolstix-squares/ and https://www.n2y.com/symbolstix-prime/). Both are available in multiple languages in addition to English.

Undoubtedly, the most powerful type of symbol for communication is an orthographic or alphabet symbol – the letters A/a, B/b, C/c, D/d, and so forth, and words that are composed of them. We use letters and printed words to represent many ideas every day -- you're using these symbols right now in order to read this lesson! The ability to manipulate the 26 letters of the English alphabet enables someone in an English-speaking context to communicate virtually any message they want, as long as their communication partner is literate in the same language. Early, systematic literacy instruction is essential in order for this to occur. Even someone who does not know how to read fluently might be able to use written words to communicate at least some messages. For example, Jordan can recognize words for many of the foods he eats regularly, such as "Kellogg's Rice Krispies" and "peanut butter." He has several pages of “food words” in in his communication book and when he wants to ask for something to eat, he simply points to the word.

There are both advantages and disadvantages to using nondigital techniques for communication. The disadvantage is that someone must take responsibility for keeping the device updated with messages (i.e., symbols) that the person needs to communicate.

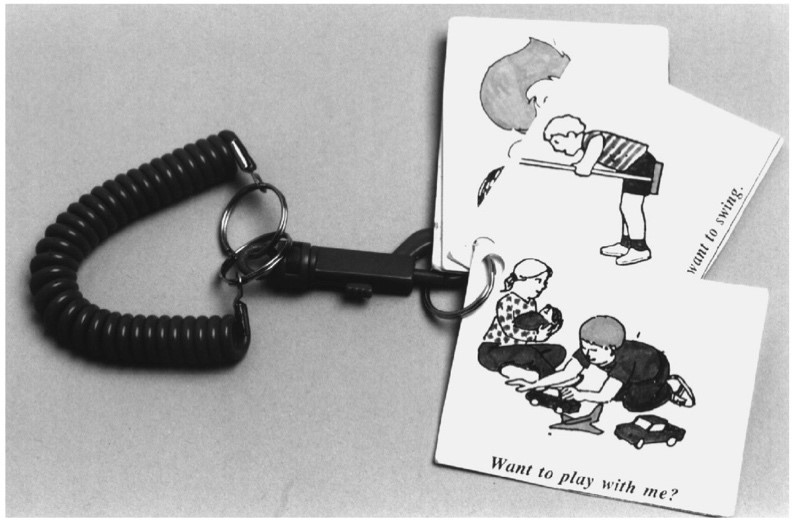

The advantages are that they are relatively inexpensive; can be designed so they are transportable; and can be used in flexible, individualized ways. For example, Gurjinder has a few symbols attached to a loop that hangs on his belt so that he can use his hands freely on the playground equipment at school (Figure 3). He can ask his friends to play and can also choose where he wants to play next (e.g., on the swings, slide, etc.). This is just one component of Gurjinder’s AAC system.

Figure 3: Gurjinder’s playground loop device

Digital Approaches

It is fair to say that most 21st century AAC systems incorporate one or more digital components that require some type of external power source (e.g., batteries or electricity. The primary advantage of digital approaches is that they produce output that can be readily understood by almost anyone. Often, a device produces speech/voice output, and sometimes printed words are displayed on a screen. For example, by touching the birthday cake symbol on his AAC device, Harold can sing the “Happy Birthday” song to his brother along with the rest of his family.

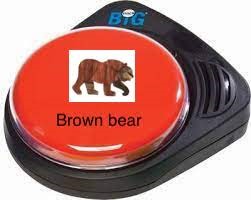

Some digital AAC devices are quite complex and expensive, while others are relatively simple to program and operate. For example, the BIGmack (AbleNet, Inc.) is a small device with a built-in microswitch, which, when activated, plays a single recorded message up to 20 seconds long. Recording a message into the BIGmack takes only seconds, using the voice of whomever sets up the device. New messages can be recorded over old ones throughout the day. So, for example, with the assistance of an education aide who is responsible for recording the messages, a kindergarten-aged student could use a BIGmack to:

- greet his teacher and classmates on arrival at school (“Hi, how are you today?”), then to

- sing “O Canada” with his classmates, then to

- participate in a language arts lesson by reciting the repeating line of a story during a shared reading activity (e.g., “Brown bear, brown bear, what do you see?”) and then to

- call out “Duck, duck, duck, duck, goose!” while a classmate touches each child’s head in the circle during this game.

As you can see, a device like the BIGmack might not do very much, but with some creativity and planning, it can be a very useful tool for classroom participation!

Figure 4: BIGmack with a “Brown bear, brown bear…” message for a shared reading activity.

Other digital devices and apps are capable of delivering hundreds and even thousands of messages, often in more than one language. As with nondigital devices, messages can be represented using digital photographs, line drawings, and alphabet symbols. Videos can also be added to the list of options; for example, Hoa can now show her friends brief video clips of her summer trip to San Diego, in addition to sharing photos and postcards. Some digital devices are “dedicated” for communication and cannot be used for other purposes, while others – most notably the iPad – can be used in multiple ways, depending on the on the app(s) that are installed. For example, iPad apps are available to create and display personalized visual scene displays, visual schedules, and social narratives.

Figure 5: Digital visual scene display for a birthday party. Hot spots (rectangles) show areas that speak a related message when activated (e.g., from left to right, back: mom, dad, balloon, Uncle Tim, front: present, candle, the “Happy Birthday song,” Joey blow, present, grandpa); hot spots are invisible on the actual display.

The advantage of digital AAC devices and apps is that they can contain a large number of single words and pre-programmed phrases (e.g., “I need help,” “I need a break,” “I want to go to the bathroom”). In addition, many dedicated devices have other features as well, including printers, calculators, large memory capacities for storing lengthy text and speeches, and the ability to interface with standard computers. The vast majority of devices and apps use high quality synthetic speech that is easy to understand. On the other hand, one of the major disadvantages of digital devices is that they are more cumbersome and more vulnerable to simple wear and tear than are nondigital techniques. They can break down (which may require expert repair specialists); their batteries can run down or fail; the switches used to operate them can fail to function; a change in location can make it impractical to transport them; and they require someone to program messages into them on a regular basis. In addition, it is important to emphasize that having a digital device or app does not make a person a good communicator any more than having a basketball makes someone Michael Jordan! iPads and other digital devices are tools for communication, and people who rely on them will need to be taught how to use them in meaningful ways, just as they are taught to use other communication techniques. They should not be seen as “quick fix” solutions to communication difficulty.

Designing an AAC System

One of the most common errors made by family members who support a person requiring AAC is to fail to take a systematic approach to decision-making. For example, with the best of intentions, a parent may purchase an iPad and communication app on the recommendation of a friend or teacher, without first assessing if a digital approach is most appropriate for the individual and/or without understanding the learning and programming demands of the app. The result is often frustration and abandonment of the system, in addition to the wasted financial costs that were incurred. This scenario can be avoided by taking a multidisciplinary approach to decision-making that includes family members and appropriate professionals who know the person well and can share information about their current communication, motor, and learning skills. Typically, the team should include the person him- or herself, family members, a speech-language pathologist or educator with AAC expertise, and other service providers as needed (e.g., a teacher, occupational therapist, vision specialist, psychologist and/or learning consultant). Once the person’s strengths and needs have been identified, team members should develop a plan for designing the AAC system and teaching the individual to use it. Two of the most important decisions have to do with the type(s) of symbols to be used and the types of messages that will be available for communication.

Symbol Selection

It's important to think carefully about what types of symbol to use with each individual, because the same symbols are not necessarily best for everyone at the outset of instruction. The most important consideration is that the symbols should be easy for the person to learn to use for communication. The more you know about a person’s interactions with pictures and other symbols, the more likely it is that you will make a successful selection. For example, if an individual often spends time looking at pictures in books and magazines, then these types of symbols might be readily used within a communication system. If you lay out a variety of symbols that range from color photographs to clip art to black-and-white line drawings and notice that the person seems most interested in photographs, it may be helpful to start with such symbols. Ultimately, the answer to the question “which type of symbol is best?” will only be answered by observing how readily an individual learns to use the symbols in a communication system.

Messages

Perhaps the most important decision to be made involves the messages that are included in the AAC system. Communicative messages can be divided into four main categories, according to their functions: (a) wants and needs; (b) information sharing; (c) social closeness; and (d) social etiquette (Light, 1988).

Wants and needs messages are the easiest to learn and use. Young children first communicate about wants and needs when they say things like: "I want ; "Give me ;" "No;" and "I don't want ." Both nondigital and digital communication systems should contain symbols that a person can use to make requests for food, activities, preferred items, and people. There should also be symbols that enable the person to say “no,” ask for a break, ask for help, and ask to be left alone.

Information sharing messages enable a person to share information with classmates, teachers, family members, and others. For example, most parents ask their children, "What did you do at school today?" when they come home after school. In addition, school-aged children and adolescents have a need to exchange more complicated information, such as when they want to ask or answer questions in class. Symbols that correspond to the vocabulary of the lesson (e.g., symbols of the sun, moon, stars, and planets for a lesson about the solar system; gardening symbols for a lesson about how plants grow (Figure 5) enable an individual to share information and enable participation in these types of interactions.

Figure 6: Line drawing symbols on an AAC display for a lesson unit about plants and how they grow. As part of the unit, students in the class planted an outside garden.

Often, the purpose of communication is not to get what we want or to share information -- it's simply to connect with other people and enjoy each other. Every person needs to be able to engage in such social closeness interactions -- to get the attention of others, to interact in positive ways, and to use humor to connect to other people. At least some of the symbols in a communication system should be related to messages for social closeness (e.g., “Let’s go play!” “That was great!” “How are you today?”).

Finally, a fourth purpose of communication has to do with the routines for social etiquette that are important in specific cultures. In North America, for example, people are expected to say "please," "thank you,” "excuse me," and “you’re welcome” in certain situations. It's also considered polite to say "hello" or "goodbye" when meeting or leaving someone and to shake someone's hand if it's offered. People who reply on AAC should be provided with symbols that enable them to interact with others in ways that are culturally acceptable and respectful.

How can you determine which messages should be included in an AAC system? Some questions to consider include:

- What will be most motivating for the person to communicate? It is critical to introduce an AAC system using messages that the person will be motivated to use, from all four categories. It is important not to limit communication to “wants and needs” messages alone -- how boring!

- Which messages will the person need to communicate on a regular basis (i.e., daily) or frequently (i.e., several times in a day)? Some examples might include greetings, requests for help, “yes,” “no,” requests related to basic wants and needs (bathroom, water, food, etc.), and social etiquette messages (e.g., “please,” “thank you”).

- Which messages will facilitate participation (e.g., information sharing) in family school, or community activities? For example, a student might tell his mother what he did at school today by showing her “remnants” from various activities, such as paper scraps from his art project or the flyer he got at the school assembly.

- Which messages will enable the person to participate in social interactions? For example, a secondary school student at a pep rally might need a message on his BigMACK that says “Go, team, go!”People of any age might want to talk about their family; fun events they did in the past; and favorite topics such as basketball stars or cars by using a nondigital or digital “scrapbook” with photographs, cards, magazine pictures, and remnants that represent motivating topics.

Supporting AAC System Use

Just as the creation of the plan for developing an AAC system is a team approach, so too should be the plan for implementation. A person will become a successful communicator only if everyone who interacts with her knows how her AAC system works (e.g., how she turns on the digital device and accesses the vocabulary, what the symbols she uses mean) and expects her to communicate with them by creating situations in which communication will be necessary. The five main principles that form the basis of AAC implementation are discussed in the sections that follow.

Provide many opportunities for communication, all day, every day. Once the person has access to an AAC system that accommodates a wide range of messages, it is important to provide numerous opportunities for system use. In the context of enjoyable and motivating activities, provide opportunities for the person to ask questions, greet others, make choices, express their feelings, comment on what is happening, and ask for items or activities that are preferred. For example, when Seo-Jun and her mom go to the mall, her mom supports Seo-Jun to greet every storekeeper, make clothing and drink choices, talk about how she feels (e.g., excited, tired), make comments (e.g., too loud, pretty shoes, ugly shoes), and ask for what she wants (e.g., more socks, home now?). In a one-hour visit, Seo-Jun had over 30 opportunities to communicate! Practice makes perfect – and the more practice, the better!

Model AAC use. Most people acquire new skills by observing others and then trying to do what they see others do. So, it is important to model AAC use by talking and either signing or pointing to AAC symbols at the same time. This helps the person to learn the meanings of the manual signs or symbols as well as where the symbols are located in a nondigital or digital system. It may also help the person understand what is being said to them, because the spoken words are paired with manual signs and pictorial or written symbols. Many research studies have shown that modeling AAC in this way throughout the day can have a beneficial effect on symbol learning, comprehension, and use (Allen et al., 2017; Sennott et al., 2016).

Emily communicates in English, Spanish, and AAC. She uses a bilingual iPad app at home and at school. In this video, her mother talks about using modeling to teach Emily where the words on her AAC device are located: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RFuKgRI3vpI

Wait for the person to communicate. Communication with AAC is not easy, especially in the beginning! For many people with a language challenge, it takes extra time to understand what is being said to them. It also takes extra time to figure out when to take a turn and how to go about doing so. Finally, it takes extra time and effort to think of what to say and then produce the manual sign(s) or find the symbol(s) that are needed to say it. All of this means that extra time – and patience! – is required of communication partners. So, it is important to resist the urge to jump in quickly, rather than waiting for the person to construct a message.

Respond to all attempts to communicate. Remember that the goal of any AAC intervention is successful, multimodal communication – however that occurs! A teenager who nods “yes” when asked a question should not be asked to “show me the sign for yes,” when the meaning of the nod was perfectly clear. An adult who brings a newspaper advertisement for running shoes to his support person and then points to himself should not have to “show me what you want on your iPad,” when the request for new shoes was obvious in the first place. Questions require answers, comments require comments in return, and social overtures require social responses, regardless of the modality that is used.

Make it fun! By providing numerous opportunities, modeling, waiting, and responding to all attempts, we deliver the message that AAC system use is easy, fun, and useful – not difficult, frustrating, and unproductive. When people are successful communicators, they will want to communicate more, not less, because they understand the power of communication.

Maya started using AAC when she was 2 years old. Over the years, she has used a wide variety of AAC techniques. Her AAC journey was documented by her parents, and can be viewed in this video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UyGr7_B2Nrk. Maya has also learned to read and write, as you can see here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iE1YimUWDPo

Summary

As you can see, there are many issues to consider when designing an AAC system. You need to think about the types of symbols you will use, the messages the system contains, and many other factors. It can be overwhelming if you think that you have to “get it just right” from the very beginning. The truth is that even the most experienced communication AAC professionals often need to experiment with various options before they find the best solution for a particular individual. So, don’t be discouraged, and remember--helping a person with limited speech to communicate is probably THE most valuable gift you can offer!

References

Allen, A., Schlosser, R., Brock, K., & Shane, H. (2017). The effectiveness of aided augmented input techniques for persons with developmental disabilities: A systematic review. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 33, 149-159.

Beukelman, D. R., & Light, J. C. (2020). Augmentative and alternative communication: Supporting children and adults with complex communication needs (5th ed.). Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes.

Frost, L. A., & Bondy, A. (2002). The Picture Exchange Communication System training manual (2nd ed.). Newark, DE: Pyramid Educational Products, Inc.

Ganz, J., & Simpson, R. (2019). Interventions for individuals with autism spectrum disorder and complex communication needs. Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes.

McNaughton, D., & Beukelman, D. (Eds.) (2010). Transition strategies for adolescents and young adults who use AAC. Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes.

Millar, D.C., Light, J.C., & Schlosser, R.W. (2006). The impact of augmentative and alternative communication intervention on the speech production of individuals with developmental disabilities: A research review. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 49, 248-264.

Sennott, S., Light J., & McNaughton, D., (2016). AAC modeling intervention research review. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 41, 101-115.

Soto, G., & Zangari, C. (2009). Practically speaking: Language, literacy, and academic development for students with AAC needs. Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes.

Wilkinson, K., & Finestack, L. (2021). Multimodal AAC for individuals with Down syndrome. Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes.

Additional Resources

- For more information about AAC in general and AAC research, visit the website of the International Society for Augmentative and Alternative Communication (ISAAC): https://isaac-online.org/english/home/.

- The U.S. Rehabilitation Engineering Research Center (RERC) on AAC is a collaborative center committed to advancing knowledge and producing innovative engineering solutions in augmentative and alternative communication (AAC): https://rerc-aac.psu.edu/.Among other things, they have produced numerous webcasts and instructional modules on various AAC topics (https://rerc-aac.psu.edu/dissemination/webcasts/ -- all of which are free and offer evidence-based information.

- Visual scene displays can be created using apps such as Scene Speak (https://www.goodkarmaapplications.com/scene-speak1.html),

Snap Scene (https://apps.apple.com/us/app/snap-scene/id1057732816), ChatAble (https://therapy-box.co.uk/chatable),

and AutisMate (https://learningworksforkids.com/apps/autismate/)

3904dac9933a4457b74f6a0eb20db866.tmb-fullpage.png?Culture=en&sfvrsn=c03e9ef8_2)