MEET JAMES…

James is a 16 year old with autism and an intellectual disability. He generally is a reasonably contented individual but has some anxieties in daily life. He lives in a stable and supportive home environment. He some times perseverates over worries, and recently overheard another youth describing the COVID-19 outbreak. Afterward,he voiced to his father his worries. He became consumed with fear and upset about the potentially devastating effect of COVID-19. His parents reassured James that the health professionals, including public health personnel and infection disease researchers, are working extensively to minimize the impact of COVID-19. They did their best to balance being honest about real concerns and risks, but reassuring James that people are working to ensure safety in the community. They also used these conversations to teach about hygiene and preventive measures to optimize safety. They used the example of the SARS pandemic in 2003, and how that pandemic also imposed some infection spread restrictions which eventually ended and life resumed as relatively normal.

After repeated conversations, James has been able to better understand that there are people working hard to keep him, his family, his community and our world as safe as possible. Hearing the story of SARS and that there is a potential end in sight seemed to be a help and give hope to James, as he needed a sense that the present risks of infection spread and the closures to his community programs and activities would one day end. Once he understood the reason for all of these changes, he seemed somewhat better able to accommodate these shifts, and go on with his daily life. He still needs reassurance periodically and his family continues to be open to talk about the situation, but sometimes gently direct him to focus on how he will get through this rather than going down a deep path to perseveration and depression. His mother is working with James on a scrapbook entitled, “How to Manage During COVID-19.” With the support of his mother, James has inserted photos of favorite activities that can be done in the context of restrictions, school closures, recreation centre closures,library closures and other circumstances. He now periodically tells others that, “it’s harsh, but we’ll get through this just like they did during SARS.” His parents have acknowledged him for his strength of character, and he seems to feel proud about his resolve despite his worries. He now understands that others are working to ensure his and others’ safety, and address the virus.

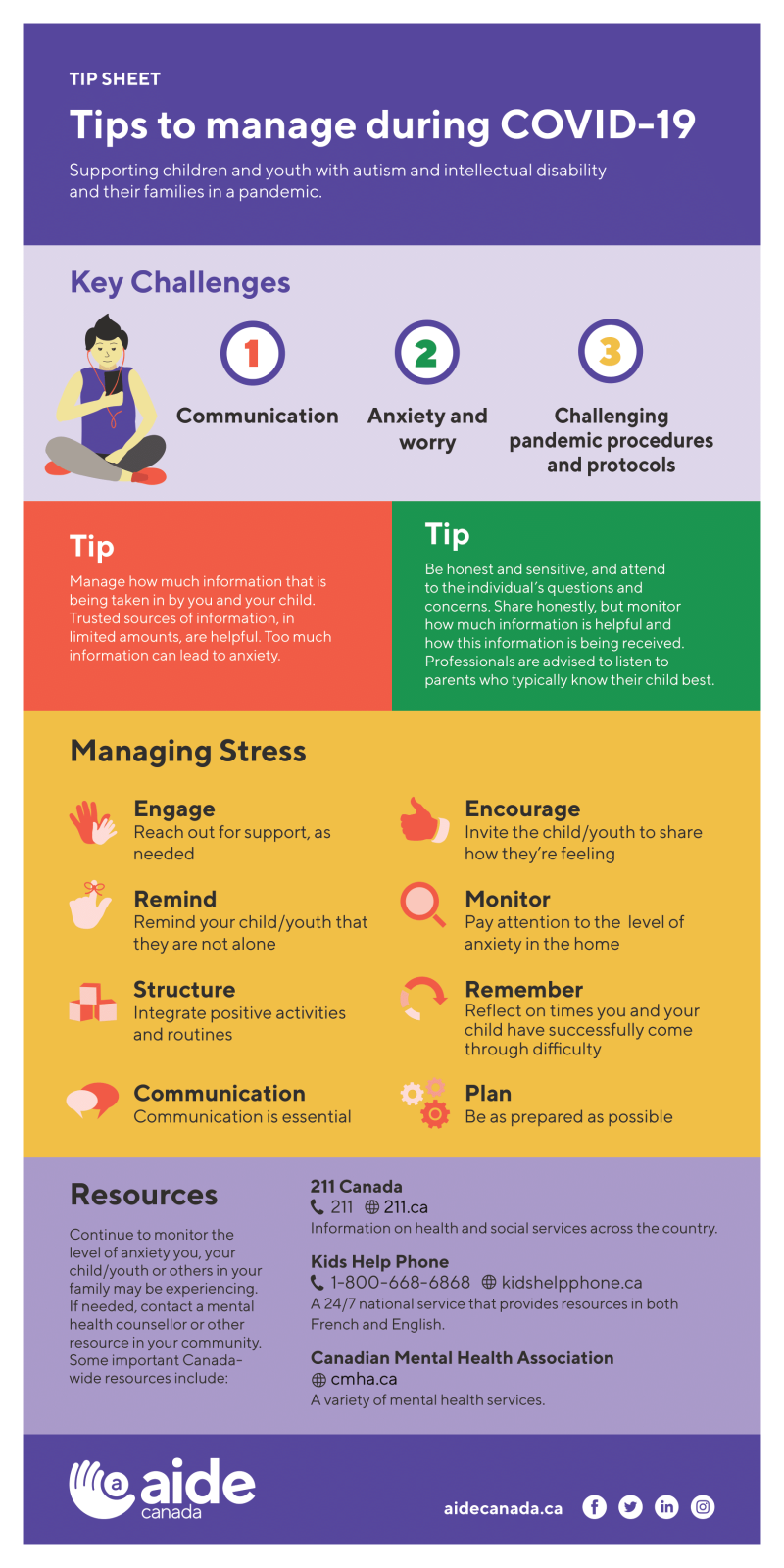

It is important to consider the needs of people with autism and intellectual disabilities at difficult times like this. A team at the Hospital for Sick Children researched the experiences of children and families during a past pandemic – SARS in 2003 (Koller, Nicholas, Gearing, & Kalfa, 2010; Koller, Nicholas, Goldie, Gearing, & Selkirk, 2006; Nicholas, Gearing, Koller, Salter, & Selkirk, 2008). This research included children and family members who spent time in quarantine or in the hospital. While not specific to children and youth with autism or intellectual disability, they found key challenges for children and families receiving health care services during this difficult time, as follows.

COMMUNICATION

Good communication included regular communication with children, especially when they or members of their family were in quarantine. Ongoing communication within families is especially important in helping children understand that their families as well as health care professionals and others are doing their best to keep them safe. We also learned that overwhelming people with negative or frightening information can heighten worry and struggle. It is important to listen to parents about what and how information should be shared with their children.

Tip: Manage the amount of information that is being taken in by you and your child. Reputable sources of information, in limited amounts, are helpful. Too much information can cause anxiety. Turn off or limit the news when children are present to minimize information about COVID-19, and details of events or stories that may be upsetting. Monitor and if needed, decrease screen time for children and youth who have easy access to media coverage.

Anxiety and worry may be very real for children, even if it isn’t verbally expressed

When we’re stressed as we are during COVID-19, it may be more difficult to avoid sharing negative messages and worries. But be careful to not worry your child. Don’t forget that what we say and how we say it will be heard and taken in by children. On the other hand, withholding information can be harmful if children get this information from somewhere else. Observe how your child is handling the negative messaging related to COVID-19.

As demonstrated by James, help in managing difficult information is important, potentially with reassurance, as needed, that responsible adults are doing their best to keep people safe.

Pandemic procedures and protocols may be challenging for some children and youth

Some children, youth and adults may not understand the need to follow infection safety procedures. For example,hand hygiene, not touching one’s face and mouth, and social distancing, may be difficult for some children to understand and do.

Teach and model safe practices for your child. For instance, you could teach and model hand washing. For some, it maybe helpful to talk through or visually cue each step. Social narratives, video, pictures and role modelling may be helpful in teaching these practices.

Interruptions and changes to daily routine are common in pandemics like COVID-19. Rules can change daily. This can be very difficult.

Social narratives or visuals/pictures may help to explain these changes. Writing a ‘rulebook’ that highlights change as part of the ‘new norm’ may help prepare for further changes along the way. As much as possible, build structure and routine into daily schedules,especially as typical daily activities (like going to school) change. James’ mother guided him in developing a scrapbook on what he could do despite social distancing. For James, that helped avoid feeling distraught about all the things he could no longer do because of program and community restrictions.

Helpful practical strategies are increasingly available. For example,researchers at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill offer an autism-focusedCOVID-19 Toolkit that introduces strategies such as social narratives, taskanalysis and strategies for calming. For more detail, view: https://ed.unc.edu/2020/03/19/unc-team-creates-online-toolkit-for-those-supporting-individuals-with-autism-during-covid-19-epidemic/

What are strategies that could help your child?

MANAGING STRESS IN A PANDEMIC

Amidst the strain we’re experiencing due to the COVID-19 pandemic, here are a few tips for supporting children/youth and others who are worried or distressed.

- Reassure the child or youth that fear and worry are a normal and natural reaction.

- Recognize that it is good that the child/youth is sharing how they’re feeling about this situation. Listening to their concerns is important in better ensuring they feel heard. This may help decrease difficult feelings being kept inside. Encourage them to ask questions and express concerns.

- Remind your child/youth that he or she is not alone. You could usereassuring phrases such as, “Even though this situation is difficult, we’ll gothrough it together.” This may open opportunities for them to express theirquestions and concerns.

- Some children/youth may convey their worries on their terms and in theirown way. Waiting for the right moments sometimes opens opportunity forcommunication about worries and struggles. Let your child/youth know that you are available to talk about COVID-19or any other concerns if and when they want and need to. For some children/youth, good moments toshare are when driving in a vehicle or before bed, but this of course variesfor different children.

- Remind your child of other difficult times and how you made it throughthose times. What helped get you throughthose tough times? Consider strategiesthat could be used now.

- Plan: Being as prepared as possible may lessen anxiety. This includesdoing what you can to be organized and ready for what may come. Considering how you would manage if you or yourchild became unwell due to COVID-19 is important. It may help to know that you are prepared asbest you can be. Later in the Toolkit,we will offer tips for you and your child in the possibility that you need tobe separated due to social isolation requirements or quarantine.

- Communication is critical at this difficult time. This includescommunication between children/youth and their family members, as well as withhealth care providers or support workers.

Tip: Be honest and sensitive, and respond to the child/youth’s questions and concerns. Share honestly, but watch how this information is being received. Professionals are advised to listen to parents who typically know their child best.

- Take time to do what you and/or your child enjoy (favorite activity,music, watching a movie, etc.). Stay connected with others via social media or other ways that maintain connection but meet community safety rules and guidelines.

- Watch out for continued sadness, depression, distress, perseveration,anxiety, overwhelm, nervousness, agitation and/or hopelessness. Continue to monitor the level of difficulty you,your child/youth or others in your family may be experiencing. If needed, contact a mental health counsellor or other resource in your community. Resources to access and/or find mental health services include the following and there maybe others in your community that could be of help:

- Kids Help Phone: A 24/7 national service that provides resources in both French and English, including counselling, referrals, and information. You can call 1-800-668-6868 to connect with a counsellor, or visit https://kidshelpphone.ca/ for more information.

- Canadian Mental Health Association:Provides a variety of mental health services, with locations across the country. Potential services includecrisis and navigation services. Contact details and locations can be found through https://cmha.ca/find-your-cmha

- 211 Canada: Run by the United Way, 211 provides information on health and social services in regions across the country. Dial 2-1-1 or visit www.211.ca for more information.

Potentially Shifting Role of Parents if either the Child or Parent is Quarantined and/or Hospitalized

A lesson related to families of children treated during the SARS outbreak was that parents’ roles sometimes shifted, often in instances in which the child or parent was quarantined and/or experiencing illness. This sometimes meant that health care workers or other adults became the primary caregiver of a child. Sometimes parents’ access was limited because of quarantine or illness. Children, parents and health care providers found this challenging. Sometimes, health care providers who cared for and supported children, felt challenged especially since they didn’t know the child and what might interest or sooth them. Health care workers often did not have much time to spend with an individual child.

It is recommended that you consider the following steps, with this in mind:

- Prepare for possible care alternatives and separation, if required. While maintaining hope and staying as positive as possible, plan for the possibility of separation. For your child, who would be ideal caregivers, and what would be helpful distractions if she/he was hospitalized or quarantined with or without you there? (Remember that if your child became exposed to COVID-19, it is likely that you and others in the family also would have been exposed and may need to be isolated).

- Make a list of what your child needs and what would be soothing and helpful distractions in hospital or another place. What does your child enjoy doing that could be enjoyed in confined spaces? A few ideas of desired activities and items might be: art (paper, pencils, pencil sharpeners, crayons), computer games (don’t forget chargers), Lego, puzzles, books and audio books, activity books, fidgets, DVDs/DVD players, and music/musical instruments (just to name a few).

In case you were not able to be with your child (for instance, if you were quarantined in a different setting), a list of care strategies and tools for alternative caregivers would be helpful. Activity 1 may help in determining what activities and items may be engaging and helpful as a distraction for your child.

With this list, you can create a ‘Care Pack’ and keep it in a safe place. Then the Care Pack can be immediately accessed, if needed. It also would be wise to keep a list of these ‘desired’ Care Pack items in case the items get lost or cannot be accessed in an emergency situation. As an aside, the Care Pack might be helpful if your child needs to go to the emergency department or is admitted to hospital for another reason. Some parents may find it helpful to write a letter to their child that they can read during an emergency situation. In the letter to your child, consider what stories or shared memories or sayings might be soothing for your child.

Tip: In choosing where to keep the Care Pack in your home, it may be best not to share its location with the child if they would be inclined to access it before it’s needed. Depending on how appealing the items in the Care Pack are to the child (hopefully they are very appealing!), knowing its whereabouts could risk it being accessed prior to being needed. If that happens, be sure to replenish the Care Pack.

Tip: Keep a copy of your list of desired items and activities in case the items in the Care Pack get removed or lost. This list also could be shared with other potential caregivers.

WHEN MOVING INTO AND THROUGH THE PANDEMIC, HOPE FOR THE BEST YET PLAN…

There are many things to consider as we respond to COVID-19. An important family consideration is who can care for your child if you are unable to due to illness or quarantine. Here are a few ideas to consider when seeking a trusted ‘circle of care’ for your child.

Consider Enlarging Your Child’s Circle of Care

Even though our socializing goes down in a pandemic, the need for support and care for one another may be increased. We’ve already seen less access to school andcommunity resources. It is important for you consider supports and alternativecaregivers for your child, if needed, during a period of potential isolation.

If needed, who would you want to be ‘on deck’ to substitute for youand/or, if relevant, your partner in providing care to your child? If you were to become ill, would they be readyand comfortable to take over caregiving? What would you want others to know about your child/youth and her/hiscare needs? What would they be requiredto know about her/his health and mental health needs? What would your child like others to knowabout her/him?

In the next Activity, your child’s needs can be written down. This list could be given to an alternative caregiver or otherwise considered if your child should need to be hospitalized.

MOVING FORWARD

COVID-19 has brought anew, difficult and shifting reality. It is important for families to have access to up-to-date information about this situation as well as resources and strategies for moving forward. We needto guard against becoming overwhelmed by news and negativity. And as we plan and prepare as best we can, we need to hold onto hope and remember that “this too shall pass”.

There are credible sources of information regarding COVID-19. For more information, the following sources may be helpful:

- Government of Canada website on COVID-19:

https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/diseases/coronavirus-disease-covid-19.html - The World Health Organization website on COVID-19:

https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019 - Centers for Disease Control and Prevention:

https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prepare/children.html

Research Sources

Bruce-Barrett, C., Matlow, A., Rafman, S., & Samson, L. (2007). Pandemic influenza planning for children and youth: Who’s looking out for our kids? Healthcare Management Forum, 20-24.

Campbell, V. A., Gilyard, J. A., Sinclair, L., Sternberg, T., & Kailes, J. I. (2009). Preparing for and responding to pandemic influenza: Implications for people with disabilities. American Journal of Public Health, 99(S2), S294-S300.

Cieslak, T. J., Evans, L., Kortepeter, M. G., Grindle, A., Aigbivbalu, L., Boulter, K., Carroll, R. W., Cumplido, S., Danforth, A. G., Fry, C., Gaensbauer, J., Hume, J. R., Husain, A., Kelleher, A., Kratochvil, C. J., Kunrath, C., Morgan, J. S., Schwedhelm, M. M., Shane, A. L., Tennill, P., Yager, P. H., & Davies, H. D. (2019). Perspectives on the management of children in a biocontainment unit: Report of the NETEC Pediatric Workgroup. Health Security, 17(1), 11-17. https://doi.org/10.1089/hs.2018.0074. Gearing, R. E., Saini, M., & McNeill, T. (2007). Experiences and implications of social workers practicing in a pediatric hospital environment affected by SARS. Health & Social Work, 32(1), 17-27.

Koller, D., Nicholas, D., Gearing, R., & Kalfa, O. (2010). Paediatric pandemic planning: Children's perspectives and recommendations. Health and Social Care in the Community, 18(4), 369-77.

Koller, D. F., Nicholas, D. B., Goldie, R. S., Gearing, R., & Selkirk, E. K. (2006). When family-centered care is challenged by infectious disease: Pediatric health care delivery during the SARS outbreaks. Qualitative Health Research, 16(1), 47-60.

Koller, D. F., Nicholas, D. B., Goldie, R. S., Gearing, R., & Selkirk, E. K. (2006). Bowlby and Robertson revisited: The impact of isolation on hospitalized children during SARS. Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 27(2), 134-140.

Maunder, R., Hunter, J., Vincent, L., Bennett, J., Peladeau, N., Leszcz, M., Sadavoy, J., Verharghe, L. M., Steinberg, R., & Mazzuli, T. (2003). The immediate psychological and occupational impact of the 2003 SARS outbreak in a teaching hospital. Canadian Medical Association, 168(10), 1-7.

Nicholas, D. B., Gearing, R. E., Koller, D., Salter, R., & Selkirk, E. K. (2008). Pediatric epidemic crisis: Lessons for policy and practice development. Health Policy, 88(2-3), 200-208.

Nicholas, D., Patershuk, C., Koller, D, Bruce-Barrett, C., Lach, L., Zlotnik-Shaul, R., & Matlow, A. (2010). Pandemic planning in pediatric care: A website policy review and national survey data. Health Policy, 96(2), 134-142.

Peacock, G., Moore, C., & Uyeki, T. (2012). Children with special health care needs and preparedness: Experiences from seasonal influenza and the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness, 6(2),91-93.