Photo by Priscilla Du Preez on Unsplash

Treating Mental Health Conditions in Autistic Individuals: A Toolkit for Understanding Approaches to Mental Health Care

March 2021

Dr. Kailyn Turner, R.Psych. | Dr. Carly McMorris, R.Psych. |

Postdoctoral Associate ENHANCE Lab Alberta Children's Hospital Research Institute Werklund School of Education University of Calgary | Assistant Professor ENHANCE Lab Alberta Children's Hospital Research Institute Werklund School of Education University of Calgary |

Elsbeth Dodman, Honours B.A. | |

Autistic Self-advocate |

Prepared for the Autism and/or Intellectual Disability Knowledge Exchange Network (AIDE Canada)

Treating Mental Health Conditions in Autistic Individuals: A Toolkit for Understanding Approaches to Mental Health Care

Using This Toolkit

This is an overview of approaches for treating mental health conditions in autistic individuals. Many approaches can help reduce distress and enhance well-being of those on the autism spectrum1. Below, ways to adaptations interventions to meet the needs of autistic people are described. Importantly, one type of intervention is never thought about in isolation from others when treating mental health conditions. Most individuals benefit from a combination of different methods of support: psychotherapy, medication, and healthy lifestyle habits such as eating nutritious food, engaging in regular physical activity, and maintaining good sleep habits.

Please note that the text, images, and illustrative examples in this toolkit were created for informational purposes only. The content in this toolkit is not intended as a substitute for professional advice or support. Always seek the advice of a qualified mental health provider or your family physician with questions about your personal needs. Never disregard professional advice or delay in seeking professional services because of something you read in this toolkit.

Mental Health in Canada

The term mental health refers to a wide range of conditions that affect mood, thinking, and behaviour. For example, common mental health conditions include anxiety, depression, and Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD).2 Mental health conditions can be associated with distress and reduced quality of life.2 In any given year, 1 in 5 Canadians experience a mental health condition and by 40 years old 1 in 2 Canadians have (or have had) a mental health condition.2 This demonstrates that mental health conditions are relatively common in the general population. 70% of mental health conditions begin during childhood or adolescence,3 and young people 15 to 24 years old are more likely to experience mental health concerns than any other age group.4,5 Tragically, about 4,000 Canadians per year die by suicide, which is an average of almost 11 deaths by suicide per day.6 Suicide is the second leading cause of death for youth age 15 to 24, and is the leading cause of death for children age 10 to 14 in Canada.7,8 This indicates great need to recognize mental health needs and support wellness.

Mental Health in Autistic People

Studies suggest that mental health conditions in autistic individuals is especially high.9-14 A review of 96 studies showed that several mental health conditions often occur in autistic people. For example, anxiety, depression, ADHD, Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD), schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders, eating disorders, substance misuse, and sleep-wake conditions are reported by autistic youth and adults.15 Although the prevalence of these conditions vary widely, their occurrence is more common among autistic people than non-autistic people.15,16 For instance, some community and clinic-based studies have shown that young autistic people have a prevalence rate of 74% for one or more of these mental health conditions. 17 Another study suggested that 70% of young adults with autism experienced at least one episode of major depression, 50% had repeating depressive episodes, and 50% had an anxiety disorder.18 Young children with autism are most commonly diagnosed to have ADHD, and depression and anxiety disorders are more common in autistic teens and adults.10,15,17,19 Despite how common these mental health conditions are, they sometimes go unrecognized among individuals with autism.20 This may limit autistic people from seeking mental health care.20 Given the negative impact of poor mental health on quality of life, it is crucial to get help for these mental health conditions among all people including those with autism.15

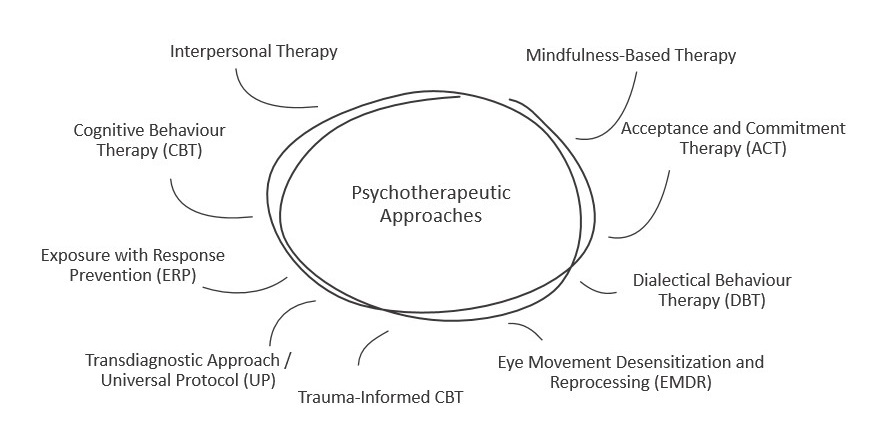

Encouragingly, there has a lot of research and improvement in care over the past 20 years.21 This research indicates the benefits of support for autistic individuals who participate in various forms of psychotherapy.21,22 Although much of this research has focused on a form of psychotherapy called Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (CBT), recent research has examined other non-CBT approaches which have been helpful among autistic individuals. Some psychotherapeutic approaches have been deemed well-established for reducing the impact of mental health symptoms, whereas other approaches show preliminary or emerging evidence,22 which means there is still more uncertainty about their impact.

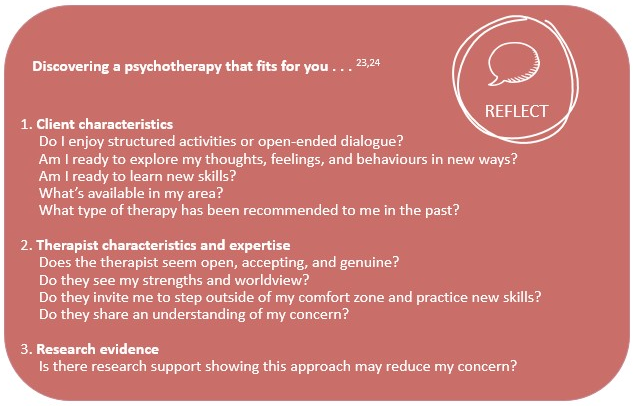

The following sections of this toolkit offer a summary of various psychotherapies. Keep in mind that many individual or personal factors impact the fit of a specific approach for someone. Finding an approach that fits for you should be done in consultation with a professional who knows you well. Trying to live in balance and thus treating the “whole individual” is important, including being sure you are engaging in personal interests and hobbies, have social connection and relationships, and engage in a healthy lifestyle such as a balanced diet, exercise, and enough sleep.

Meet James James notices that he has been increasingly anxious. He’s having trouble sleeping, settling on a task, and he continuously feels like something bad will happen even when he knows everything is fine. These feelings have started to get in the way of him completing homework and he’s becoming easily agitated in social situations. James may not have recognized this increase in anxiety right away, but now that it’s interrupting his everyday life, he knows he needs help. He talks to his caregivers about how he’s feeling and what changes he’s noticed in his behaviour. His caregivers agree that there’s been a change in James, and they call their family doctor for advice and a referral. |

Tailoring Support

Adjustments to how psychotherapy is typically provided has been recommended for autistic individuals, and should be considered regardless of the approach used:22,25,26

Therapy Delivery | - Focus on positive character attributes and strengths of the individual - Accommodate autism-related traits on an individual basis (e.g., dim lighting, noise-reducing headphones, fidget tools, access to comfort items, break space) - Clarify the individual’s preferred terms related to autism (e.g., person- or identity-first) and mental health (e.g., worried, afraid, scared, anxious) - Increase inclusion of caregivers and other key support people (e.g., parents, community or behavioural aides, respite workers) when the individual is comfortable doing so to help generalize information and new skills outside of the therapy setting - Offer a slower pace of treatment to allow for added processing time and practice (e.g., increase total number of sessions) - Plan together for home and community practice and check-in regularly about out-of-session practice - Incorporate special interests to teach, engage, and increase participation - Reduce the use of metaphors (non-direct language) and be more cognitively concrete for some individuals - Offer structured sessions with clear expectations - Use written and visual information and structured worksheets (e.g., handouts, videos, images, multiple choice worksheets) - Offer regular breaks or consider shortened sessions to maintain attention and help manage within the group setting for some individuals |

Therapy Content | - Provide psychoeducation about the relationship between autism and mental health - Explore and develop emotional awareness/recognition - Emphasize behavioural strategies such as supporting behavioural activation (e.g., purposefully scheduling in enjoyable and meaningful activities) and repeated exposure (e.g., supported, gradual exposure to a feared situation or object) - Simplify cognitive or abstract thinking-based activities for some individuals - Offer supplemental skills training (e.g., social problem solving, self-regulation) - Support healthy lifestyle behaviours related to sleep, physical activity, and nutrition |

Psychotherapeutic Approaches for Treating Co-Occurring Mental Health Conditions in Autistic Individuals

There are several psychotherapeutic approaches to help with mental health conditions in both non-autistic and autistic individuals. Some people may find they prefer a certain approach. While most people do not participate in all forms of psychotherapy, they might explore different approaches in order to discover what fits best for them. Here’s an overview of approaches with quite a lot of evidence or emerging evidence in existing research:

Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (CBT)

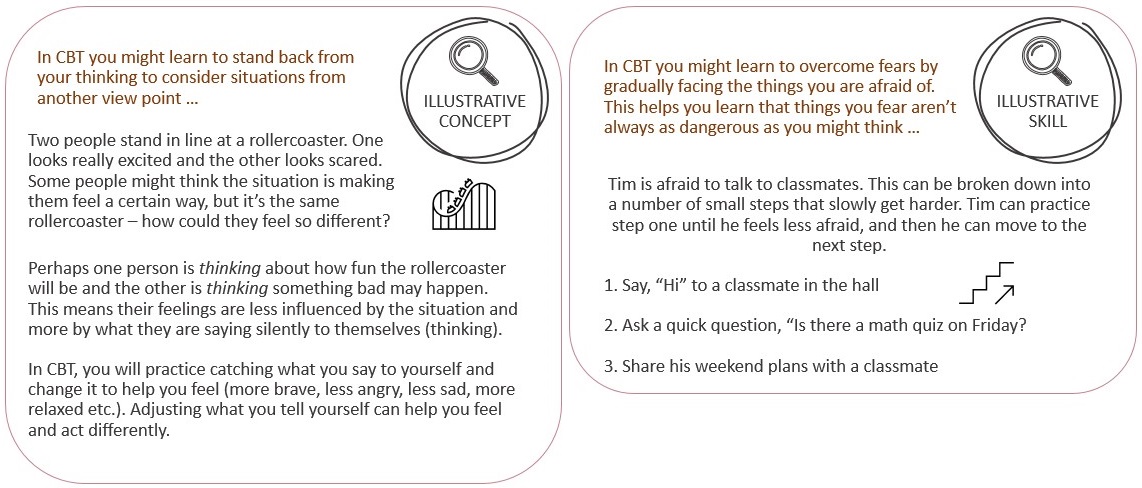

CBT is a form of psychotherapy that emphasizes the important role of thoughts in how individuals feel and act.27 Although there are different types of CBT, these types generally focus on helping people explore the way they think about what is happening around them. CBT suggests that unhelpful thoughts and the meanings people give to events can make it difficult for them to confidently approach situations.27 These unhelpful thoughts contribute to emotional difficulties such as worry and sadness. 27 To counteract these challenges, CBT helps people develop new ways of thinking in order to feel and act differently, even when the situation doesn’t change.

In CBT, people learn a range of cognitive and behavioural strategies. For example, people might learn to identify problems more clearly, develop an awareness of their automatic thoughts, and see a situation from a different perspective.28 They might explore how their past experiences can affect their present feelings and beliefs, and they might learn to develop a more positive way of seeing situations.28 CBT helps people identify unhelpful thinking patterns such as fearing the worst, overgeneralizing, thinking in ‘all-or-nothing’ ways, or focusing on how they think things should be as opposed to how they are.28 People might keep daily listings or diaries of their thoughts, feelings, and actions, and they talk with their therapist about them.28 They might role-play and receive feedback from their therapist, and they practice newly learned skills inside and outside of the therapy setting (e.g., home practice).28 Practicing new skills promotes positive change and growth.

Another part of CBT is helping people learn to face their fears or worries rather than avoid them.28 Facing fears and worries is important because although avoiding feared situations makes us feel better in the short-term, it teaches the person that the best way to control their anxiety is to avoid whatever sets it off. Avoiding feared situations takes away the opportunity to learn that, in fact, the person can handle the thing they are afraid of. When learning to face fears, the person first learns several strategies such as more positive ways to think and cope, as well as ways to calm one’s mind and body. Next, the person works with their therapist to break a feared situation down into small, manageable steps each with increasing difficulty (this is called a ‘fear ladder’).28 The person then completes the steps that gradually increase toward their most feared situation. Facing fears helps fear decrease because the person achieves success at each escalating step, and they learn that they can indeed handle whatever it is that is frightening them.27 Eventually facing someone’s fears can help break the old pattern of running away from or avoiding one’s fears in a non-helpful way, for instance, in ways that bring discomfort.27

CBT is usually:

- Led by a mental health expert (e.g., psychologist, clinical social worker, counsellor, or another therapist).

- A short-term therapy (e.g., 20 or fewer sessions).

- Facilitated 1-1 (individually) or in groups.

- Instructive (i.e., teaches a person how to perform a specific strategy or skill or provides information about a specific concept).

- Structured (i.e., follows a predictable format each session).

- Action-oriented (i.e., includes practice inside and outside of the therapy session to approach uncomfortable situations while practicing new skills).

- Goal-focused (i.e., person sets goals about what they’d like to achieve and works toward them in collaboration with their therapist).

There is considerable evidence for using modified (as listed above on pp. 5) CBT to treat anxiety and depression among children, youth, and adults on the autism spectrum.29,30 While research has shown CBT to be effective for autistic individuals with minimal to no intellectual or communication challenges, less is known about how this treatment works for individuals with these differences.31

A closely related form of psychotherapy to CBT is Exposure with Response Prevention (ERP). ERP is well-regarded treatment for obsessive-compulsive disorders in the general population.32 In ERP, people are supported to face their fears similar to how it is done in CBT (i.e., exposure).33,34 Importantly, people learn to refrain from engaging in specific urges or actions (compulsions) that they would typically perform to reduce their anxiety in the feared situation (i.e., response prevention).34 The ERP model indicates that the intensity of a person's desired response will diminish or ease over time with repeated times of being exposed to the situation they fear – if they are supported to not use the old rituals, habits or compulsions to “undo” or neutralize their fear.33,34 As such, ERP helps people eliminate undesired responses by supporting them to face their fears while preventing them.33,34 Although compulsive behaviours may seem helpful for reducing anxiety in the short-term, they get in the way of everyday life in the long-term. Importantly, the exposure offered in ERP start gradually and increase slowly overtime with a high degree of support from the therapist.

Although ERP is well-established for use with children, youth, and adults in the general population, 32 ERP has received less investigation among autistic individuals. Some early evidence suggests that modified ERP may be effective for individuals with autism who do not also have intellectual impairment.35,36 Little is known about this approach for autistic individuals with cognitive and/or language difficulties.

Check-In with James James has had four sessions of CBT and wants to continue building strategies to help himself recognize and regulate his anxiety. Having a good awareness of what he’s feeling will help him to build strategies. James’s friends are talking about using mindfulness; learning to meditate and relax. He decides to talk to his therapist about trying mindfulness to see if it’s a good fit for him. |

Mindfulness-Based Interventions

Mindfulness-based interventions are a form of psychotherapy that may include specific approaches such as Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) and Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT). These approaches have been shown to reduce distress and facilitate wellbeing in non-autistic people.37-40

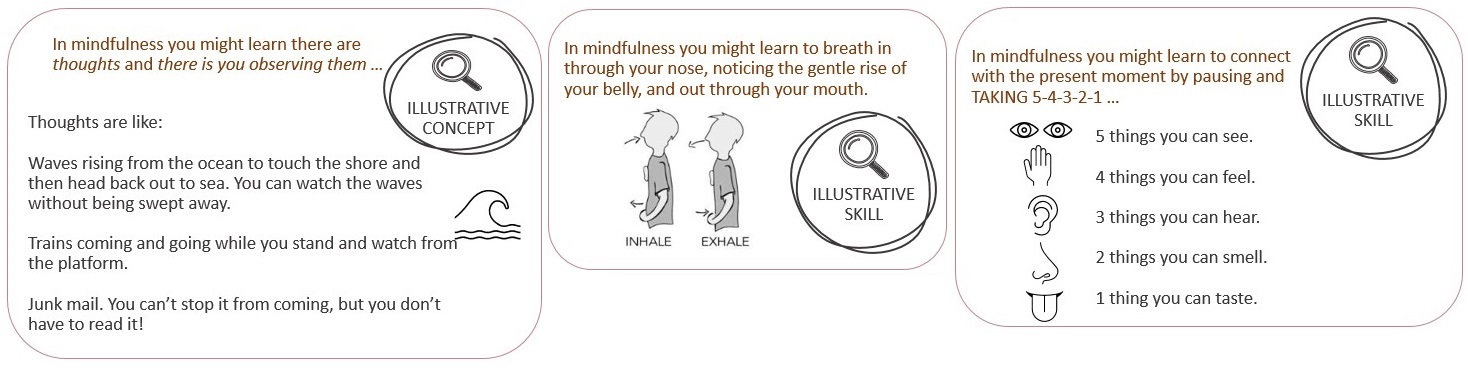

Mindfulness-based interventions emphasize kind, gentle and non-judgmental attention to the present moment or experience.41 Although there is no universally accepted definition of mindfulness, it may be understood as a state in which a person becomes aware of their physical, mental, and emotional condition in the present moment.41 Generally, people learn to pay attention to their experiences such as how their body is feeling (bodily sensations), and their thoughts and feelings. People are encouraged to accept these experiences without judging them, which can make it easier to get in touch with how one is feeling, which may help to prevent a downward spiral of negative thoughts and feelings.37 People may learn to try meditation within the therapy setting and they are encouraged to practice these approaches in their daily life.41 While meditation is a common part of mindfulness-based interventions, other strategies are also used. For instance, gentle yoga movements, stretching, sitting or walking in nature, breathing exercises, “body scans”, and “guided imagery” are some other strategies often used in mindfulness.42

Mindfulness-based interventions are usually:

- Led by a mental health expert (e.g., psychologist, clinical social worker, psychiatrist, nurse, counsellor or another therapist).

- A short- or long-term therapy (e.g., lasting 5 weeks to 12 months).

- Facilitated 1-1 (individually) or in groups.

- Instructive (i.e., teaches a person how to perform a specific strategy or skill or provides information about a specific concept).

- Structured (i.e., follows a predictable format each session).

- Action-oriented (i.e., includes practice inside and outside of the therapy session, with mindfulness at home often considered a key part of training in this approach).

- Goal-focused (i.e., person sets goals about what they’d like to achieve and works toward them in collaboration with their therapist).

Other commonly known psychotherapies that incorporate mindfulness-based techniques include Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) and Dialectical Behavioral Therapy (DBT). While ACT and DBT do not emphasize meditation, these approaches use other mindfulness exercises as core techniques to encourage more awareness of oneself and help move toward desired change.42 The essence of ACT is to learn to be aware of your personal here-and-now experience with openness, interest, and receptiveness.43 The ACT model encourages people to take committed action toward a direction they personally value.43 A key feature of ACT is to allow aspects of one’s experience to exist without necessarily enjoying or approving of them (i.e., acceptance).43

DBT also uses mindfulness as an important part of treatment wherein clients learn how to live in the moment and be fully aware of their thoughts, feelings, sensations, and impulses.44 In DBT, people learn to tolerate intense emotions, maintain positive and healthy relationships with others, and identify and change powerful feelings.44 While ACT and DBT include pieces of mindfulness, these approaches mainly focus on the thoughts and feelings experienced during the activities of mindfulness and incorporate other areas of skill development.42

Mindfulness-based interventions have had some success and seem promising in easing distress among autistic adults with minimal to no intellectual or communication challenges.45-47 Less is known about the effectiveness of mindfulness-based interventions in autistic children; however, the results of more and more research are suggesting that mindfulness may be a helpful approach for autistic children and youth.48

Check-In with James James has had eight sessions of Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy and it has been a good fit for him. He has been practicing visualizing his thoughts like channels on TV. If he doesn’t like the thought, he can change the channel and think about something else. James has also tried focusing himself when he starts to get anxious by counting things in his environment (cars, chairs, etc.). By bringing himself into the present moment he’s able to take his mind away from the anxiety he’s feeling. James has been doing well and both he and his therapist have decided to have meetings once a month as check-ins. James can return to meeting more frequently if he requires more support again in the future. |

Interpersonal Psychotherapy

Interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) is a well-established approach for treating non-autistic adults and youth with depression.49,50 IPT focuses on the back-and-forth interaction between a person’s mood and their social relationships.49 The IPT model is based on the idea that there is a ‘back and forth’ association between mood and relationships, where more negative feelings can harm relationships, and in turn, more problematic relationships can worsen one’s mood.51 As such, people learn to build better skills in forming positive relationships with others, and to increase their awareness of how their mood can influence relationships.51 Improving the quality of a person’s relationships and social functioning helps reduce their distress.51

IPT addresses interpersonal or relationship-based problems such as being social isolated or being involved in unfulfilling relationships as well as disputes or conflict between partners, family members, or close friends.52 IPT also helps someone who is dealing with grief such as the loss of a loved one or significant relationship, and major life transitions (e.g., ending a relationship, moving).52

Interpersonal psychotherapy is usually:

- Led by a mental health expert (e.g., psychologist, clinical social worker, counsellor or another therapist).

- A short-term therapy (e.g., lasting 12 to 16 weeks).

- Facilitated 1-1 (individually).

- Explorative (i.e., less rigid in how it is structured, which means less directive and structured than other psychotherapies).

- Client-led (i.e., client identifies the interpersonal or relationship-related issues they wish to address and ranks them in order of importance, while the therapist offers supportive listening and clarification of issues).

- Socially-oriented (i.e., emphasizes change in one’s day-to-day surroundings as opposed to within the individual).

Although a recent review including multiple studies showed IPT to be effective for treating depression in young people with autism,29 more research is needed to understand this approach in relation to other areas that are causing problems, for instance, in areas that aren’t focused on one’s negative mood or feelings (e.g., anxiety). Further, autistic people with accompanying intellectual disability have not been included in most of these studies, which limits our understanding of this (and other) psychotherapies for these individuals.29

Unified Protocol for Transdiagnostic Treatment of Emotional Disorders (UP)

Unified Protocol for Transdiagnostic Treatment of Emotional Disorders (UP) is an emotion-focused psychotherapy that is not focused on a diagnosis, but instead addresses underlying factors or important issues that might lead to whatever is problematic for the individual. That could be anxiety, depression, or anger-related problems.53 UP is cognitive-behavioural in nature54 – that is, it is about how we think and respond to these issues of concern. It relies on aspects of CBT as described above.

Better controlling one’s emotions (or what we call, ‘emotion regulation’) is the main focus of UP and people learn a range of skills related to emotion recognition and management of distressing feelings.53,54 Similar to other approaches, people learn to tolerate and cope more positively with strong negative emotions through exposure to these feelings. People might also learn to think about difficult situations and experiences in a more flexible manner.54 Lastly, UP includes strategies to enhance motivation, manage crises, and develop helpful skills used by key support people (e.g., caregivers, parents, partners).53,54

UP is usually:

- Led by a mental health expert (e.g., psychologist, clinical social worker, psychiatrist, nurse, counsellor or another therapist).

- A short- to long-term therapy (e.g., 21 sessions or until the client demonstrates mastery over the material).

- Facilitated 1-1 (individually) or in groups.

- Instructive (i.e., teaches a person how to perform a specific strategy or skill or provides information about a specific concept).

- Structured (i.e., follows a predictable format each session).

- Action-oriented (i.e., includes practice inside and outside of the therapy session to approach difficult or uncomfortable situations while practicing new skills).

- Goal-focused (i.e., person sets goals about what they’d like to achieve and works toward them in collaboration with their therapist).

Researchers have found that UP is effective for non-autistic adults with anxiety and depression,55,56 while research for non-autistic children and youth is less developed and more is research needed.57,58 UP has been suggested as a potentially powerful approach to addressing emotional difficulties in individuals with autism, who often struggle to a greater degree with emotion regulation than non-autistic people. 59 However, this has not yet been studied, and research is needed to test how UP can assist individuals with autism and mental health conditions. 59

Trauma-Focused Therapies

Several trauma-focused psychotherapies exist to assist individuals including children, youth, and their families overcome the negative effects of traumatic experiences which are very difficult or upsetting experiences that have happened in someone’s life. Practitioners may also use a trauma-informed approach, which considers the person’s trauma experience in other psychotherapeutic approaches (e.g., mindfulness).

Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (TF-CBT) is one evidence-based example of a specific trauma-focused therapy. 60 In TF-CBT, people are provided, first and foremost, with a secure and safe environment to share their trauma experience.60 Specifically, TF-CBT emphasizes psychoeducation and building relaxation, emotion regulation, and develops cognitive coping skills like self-monitoring and behavioural activation.60 TF-CBT also focuses on a trauma narrative, which is a technique to help individuals make sense of their experiences while also acting as a form of being exposed to and managing difficult memories.60 When completing a trauma narrative, the story of a traumatic experience may be told through talking, writing, or other artistic means.60 Sharing a trauma narrative makes traumatic memories more manageable and diminishes the painful emotions they carry.60 TF-CBT might also include a client-support person (e.g., caregiver of a child) to enhance safety for trauma triggers (upsetting issues and responses that are caused by exploring the traumatic and difficult experience). Also, a plan for keeping or maintaining newly learned skills in the future may be included in TF-CBT.60

Another trauma-focused psychotherapy is Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR).61 Similar to TF-CBT, EMDR helps a person find and process or manage traumatic memories and other difficult life experiences. During EMDR, people briefly identify to an emotionally distressing event or memory, while, at the same time, focusing on something else in their environment (an external stimulus).61 A therapist-led form of eye movement where the person uses their eyes to track the therapist’s hand as it moves back-and-forth across their field of vision is a common example.62 Other movements such as hand-tapping can also be used.62 A focus on difficult memories combined with these specific movements helps individuals gain exposure to overwhelming thoughts and emotions so that new thinking can be developed; for instance, new associations between the traumatic memory and a healthier way of managing this difficult information.61,62 These new associations or ways of thinking help move the person towards healthier mental and physical responses to their trauma and stressors.61

Specific Trauma-Focused Therapies are usually:

- Led by a mental health expert with specialized trauma-focused training (e.g., psychologist, clinical social worker, psychiatrist, nurse, counsellor or another therapist).

- A short-term therapy (e.g., lasting no more than 16 sessions).

- Facilitated 1-1 (individually).

- Instructive (i.e., teaches a person how to perform a specific strategy or skill or provides information about a specific concept).

- Structured (i.e., follows a predictable format each session).

- Therapist-led (i.e., primarily includes guided practice inside the therapy session).

- Goal-focused (i.e., person sets goals about what they’d like to achieve and works toward them in collaboration with their therapist).

Autistic people may be more likely to experience traumatic events due to a combination of individual factors, such as social and communication differences, and environmental factors, such as isolation, societal attitudes, and increased interaction with multiple service systems.63 Since the stress of traumatic events can negatively contribute to one’s overall well-being, researchers and practitioners have considered the use of trauma-focused therapies in children, youth, and adults with autism.63 This research is in its early stages and little is known about the appropriateness or helpfulness of trauma-specific therapies for autistic people. For instance, the use of TF-CBT in autistic children has been explored in the literature, but has not yet been studied in major evaluation studies.64 EMDR has been investigated in autistic adults;65 however, the effects have not yet been studied beyond single-cases.66 Much more research is needed to assess the effectiveness of trauma-focused therapies for autistic individuals.

Conclusion

Psychotherapy is a way to help people manage troubling thoughts, feelings, and behaviours so they can increase their overall well-being. 23,24 Autistic individuals are more likely than non-autistic people to experience mental health conditions, and access to tailored psychotherapy to meet their needs is important and can be very helpful. Encouragingly, there has been rapid growth in research and practice to better understand mental health in autism. To date, research indicates the benefit of psychotherapy for autistic individuals.21,22 But more research is needed to test the effectiveness of some treatments for individuals with autism, especially among those with more significant intellectual and communication differences. But preliminary findings are encouraging.22 Many personal factors of the individual may have an impact on the fit of a specific approach for that person. If you’re considering therapy, we encourage you to talk with a professional who knows you well.

How to Access Mental Health Care?

If you are interested in learning more about psychotherapy, talk to a professional in your area. Regions are quite different in terms of service availability and providers, but information for community, government, and social and health services is available across Canada.

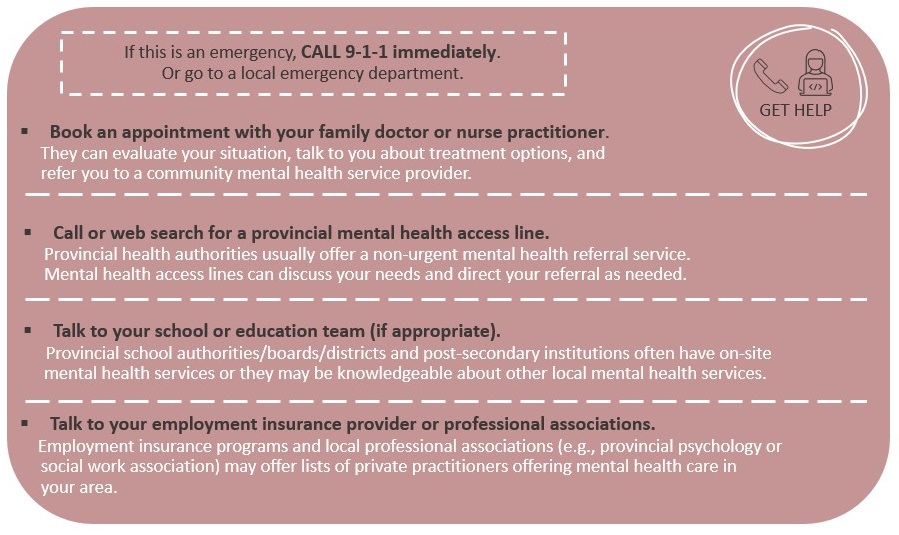

Some people experiencing mental health concerns may experience thoughts of harming themselves. If you are experiencing distress or troubling thoughts, contact the Canada Suicide Prevention Service at 1-833-456-4566 (Call) or 45645 (Text). This service is available to listen, support, and help keep you safe. If you or someone you know is in immediate danger, call 9-1-1 or go to your nearest emergency department right away. |

References

1. Camm-Crosbie, L., Bradley, L., Shaw, R., Baron-Cohen, S., & Cassidy, S. (2019). ‘People like me don’t get support’: Autistic adults’ experiences of support and treatment for mental health difficulties, self-injury and suicidality. Autism, 23(6), 1431-1441.

2. Smetanin, P., Stiff, D., Briante, C., Adair, C.E., Ahmad, S. and Khan, M. (2011). The life and economic impact of major mental illnesses in Canada: 2011 to 2041. Mental Health Commission of Canada. RiskAnalytica. https://www.mentalhealthcommission.ca/sites/default/files/MHCC_Report_Base_Case_FINAL_ENG_0_0.pdf

3. Government of Canada (2006). The human face of mental health and mental illness in Canada. Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada. https://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/publicat/human-humain06/pdf/human_face_e.pdf

4. Pearson, C., Janz, T. & Ali, J. (2013). Health at a glance: Mental and substance use disorders in Canada. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 82-624-X. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/pub/82-624-x/2013001/article/11855-eng.pdf?st=JCbO-B2p

5. Rush, B., Urbanoski, K., Bassani, D., Castel, S., Wild, T.C., Strike, C., Kimberley, D., & Somers J. (2008). Prevalence of co-occurring substance use and other mental disorders in the Canadian population. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 53: 800-9. doi: 10.1177/070674370805301206

6. Statistics Canada (2018). Deaths and age-specific mortality rates, by selected grouped causes, Canada. Table: 13-10-0392-01 https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1310039201

7. Children’s First Canada (2020). Raising Canada 2020: Ringing the alarm for Canada’s children. https://childrenfirstcanada.org/raising-canada

8. Statistics Canada. (2020) Deaths and age-specific mortality rates, by selected grouped causes, Canada. Table 13-10-0392-01 https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1310039201

9. Hofvander, B., Delorme, R., Chaste, P. Nydén A, Wentz E, Ståhlberg O, Herbrecht E, Stopin A, Anckarsäter H, Gillberg C, Råstam M, & Leboyer M. (2009). Psychiatric and psychosocial problems in adults with normal-intelligence autism spectrum disorders. BMC Psychiatry, 10(9), 35. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-9-35.

10. Moseley, D.S., Tonge, B.J., Brereton, A.V., & Einfeld S.L. (2011). Psychiatric comorbidity in adolescents and young adults with autism. Journal of Mental Health Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 4, 229-243. https://doi.org/10.1080/19315864.2011.595535

11. Simonoff, E., Pickles, A., Charman, T., Chandler, S., Loucas, T., & Baird. G. (2008). Psychiatric disorders in children with autism spectrum disorders: Prevalence, comorbidity, and associated factors in a population-derived sample. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 4, 921-929. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e318179964f.

12. Skokauskas, N., & Gallagher. L. (2012). Mental health aspects of autistic spectrum disorders in children. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 56, 248-257.doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2011.01423.x

13. Solomon, M., Miller, M., Taylor, S.L., Hinshaw, S.P, & Carter, C.S. (2012). Autism symptoms and internalizing psychopathology in girls and boys with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 42, 48-59. doi: 10.1007/s10803-011-1215-z

14. Mukaddes, N.M., Hergner, S., & Tanidir. C. (2010). Psychiatric disorders in individuals with high-functioning autism and Asperger’s disorder: similarities and differences. The World Journal of Biological Psychiatry, 11, 964-971.doi: 10.3109/15622975.2010.507785

15. Lai, M.C., Kassee, C., Besney, R., Bonato, S., Hull, L., Mandy, W., Szatmari, P., & Ameis, S.H. (2019). Prevalence of co-occurring mental health diagnoses in the autism population: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry, 6(10), 819-829. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30289-5.

16. Havdahl, A., & Bishop, S. (2019). Heterogeneity in prevalence of co-occurring psychiatric conditions in autism. Lancet Psychiatry, 6(10), 794-795. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30326-8.

17. Mattila, M. L., Hurtig, T., Haapsamo H., Jussila, K., Kuusikko-Gauffin, S., Kielinen, M,. Linna, S.L., Ebeling, H., Bloigu, R., Joskitt, L., Pauls, D.L., & Moilanen, I. (2010). Comorbid psychiatric disorders associated with asperger syndrome/high functioning autism: a community- and clinic-based study. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 40, 1080-1093. doi: 10.1007/s10803-010-0958-2

18. Lugnegard, T., Hallerback, M. U., & Gillberg, C. (2011). Psychiatric comorbidity in young adults with a clinical diagnosis of Asperger syndrome. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 32, 1910-1917. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2011.03.025

19. Hudson, C.C., Hall, L., & Harkness, K.L.J. (2018). Prevalence of depressive disorders in individuals with autism spectrum disorder: A metaanalysis. Abnormal Child Psychology, 47, 165-175. doi: 10.1007/s10802-018-0402-1.

20. Lake, J. K., Perry, A., & Lunsky, Y. (2014). Mental health services for individuals with high functioning autism spectrum disorder. Autism Research and Treatment, 502420. http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2014/502420

21. Vasa, R. A., Keefer, A., Reaven, J., South, M., & White, S.W. (2018). Priorities for advancing research on youth with autism spectrum disorder and cooccurring anxiety. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48, 925-34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-017-3320-0.

22. White, S.W., Simmons, G.L., Gotham, K. O., Conner, C. M., Smith, I. C., Beck, K. B., & Mazefsky, C. A. (2018). Psychosocial treatments targeting anxiety and depression in adolescents and adults on the autism spectrum: Review of the latest research and recommended future directions. Current Psychiatry Reports, 20, 82.doi: 10.1007/s11920-018-0949-0

23. Lambert, M. J. (2013). Bergin and Garfield's handbook of psychotherapy and behavior change. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

24. Canadian Psychological Association. (2012). Evidence based practice of psychological treatment: A Canadian perspective. http://www.cpa.ca/docs/file/Practice/Report_of_the_EBP_Task_Force_FINAL_Board_Approved_2012.pdf

25. Walters, S., Loades, M., & Russell, A. (2016). A systematic review of effective modifications to cognitive behavioural therapy for young people with autism spectrum disorders. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 3(2), 137-153. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40489-016-0072-2

26. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. (2013). Autism: The management and support of children and young people on the autism spectrum. CG 170 London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence.

27. Beck, J.S. (2011). Cognitive Behaviour Therapy: Basics and Beyond. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

28. Dobson, D. & Dobson, K.S. (2009). Evidence-Based Practice of Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

29. Cameron, L.A., Phillips, K., Melvin, G.A., Hastings, R.P., & Gray, K.M. (2020). Psychological interventions for depression in children and young people with an intellectual disability and/or autism: Systematic review. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 1-10. doi: 10.1192/bjp.2020.226

30. Hillman. K., Dix, K., Ahmed, K., Lietz. P., Trevitt, J., O'Grady, E., Uljarevic, E., Vivanti, G., & Hedley, D. (2020). Interventions for anxiety in mainstream school aged children with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review. Campbell Systematic Reviews, 16, e1086. https://doi.org/10.1002/cl2.1086

31. Blakeley-Smith, A., Meyer, A.T., Boles, R.E., & Reaven, J. (2021). Group cognitive behavioural treatment for anxiety in adolescents with ASD and intellectual disability: A pilot and feasibility study. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities. [Epub ahead of print] PubMed PMID: 33410240.

32. Law, C., & Boisseau, C. L. (2019). Exposure and Response Prevention in the treatment of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Current perspectives. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 12, 1167-1174. doi: 10.2147/PRBM.S211117

33. Lewin, A.B., Storch, E.A., Merlo, L.J., Adkins, J.W., Murphy, T., & Geffken, G.R. (2005). Intensive cognitive behavioral therapy for pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder: A treatment protocol for mental health providers. Psychological Services, 2(2), 91-104. https://doi.org/10.1037/1541-1559.2.2.91

34. Storch, E. A. (2005). Pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder: Guide to effective and complete treatment. Contemporary Pediatrics, 22(11), 58-70.

35. Lehmkuhl, H. D., Storch, E. A., Bodfish, J. W., & Geffken, G. R. (2008). Brief report: exposure and response prevention for obsessive compulsive disorder in a 12-year-old with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 38(5), 977-981. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-007-0457-2

36. Elliott, S.J., McMahon, B.M., & Leech, A.M. (2018). Behavioural and cognitive behavioural therapy for obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) in individuals with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 11. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD013173.

37. Cooper, D., Yap, K., & Batalha, L. (2018). Mindfulness-based interventions and their effects on emotional clarity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 235, 265-276. https ://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2018.04.018.

38. Blanck, P., Perleth, S., Heidenreich, T., Kröger, P., Ditzen, B., Bents, H., & Mander, J. (2018). Effects of mindfulness exercises as stand-alone intervention on symptoms of anxiety and depression: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 102, 25-35. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2017.12.002.

39. Potes, A., Souza, G., Nikolitch, K., Penheiro, R., Moussa, Y., Jarvis, E., Looper, K., & Rej, S. (2018). Mindfulness in severe and persistent mental illness: A systematic review. International Journal of Psychiatry in Clinical Practice, 22, 253-261. https://doi.org/10.1080/13651 501.2018.14338 57

40. Wang, Y.Y., Li, X. H., Zheng, W., Xu, Z.Y., Ng, C.H., Ungvari, G.S., Yuan, Z, & Xiang, Y. (2018). Mindfulness based interventions for major depressive disorder: A comprehensive meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Affective Disorders, 229, 429-436. doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.12.093.

41. Kabat-Zinn, J. (2003). Mindfulness-based interventions in context: Past, present, and future. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10(2), 144-156. doi.org/10.1093/clips y.bpg016

42. Chiesa, A, & Malinowski, P. (2011). Mindfulness-based approaches: Are they all the same? Journal of Clinical Psychology, 67(4), 404-24. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20776.

43. Hayes, S.C., Strosahl, K.D., & Wilson, K.G., (2012). Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: The process and practice of mindful change (2nd edition). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

44. Linehan, M.M. (2021, March 5). What is Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT)? Behavioral Tech: Linehan Institute Training Company. https://behavioraltech.org/resources/faqs/dialectical-behavior-therapy-dbt/

45. Sizoo, B. B., & Kuiper, E. (2017). Cognitive behavioural therapy and mindfulness-based stress reduction may be equally effective in reducing anxiety and depression in adults with autism spectrum disorders. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 64, 47-55. https ://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2017.03.004.

46. Spek, A. A., van Ham, N. C., & Nyklicek, I. (2013). Mindfulness-based therapy in adults with an autism spectrum disorder: A randomized controlled trial. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 34(1), 246-253. https ://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2012.08.009.

47. Conner, C. M., & White, S. W. (2018). Brief report: Feasibility and preliminary efficacy of individual mindfulness therapy for adults with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48(1), 290-300. https://doi.org/10.1007/s1080 3-017-3312-0.

48. Hartley, M., Dorstyn, D., & Due, C. (2019). Mindfulness for children and adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder and their caregivers: A Meta-analysis. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 49(10), 4306-4319. doi: 10.1007/s10803-019-04145-3.

49. Mufson, L., Dorta, K.P., Moreau, D., & Weissman, M.M. (2004). Interpersonal psychotherapy for depressed adolescents. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

50. Frank, E., Kupfer, D.J., Wagner, E.F., McEachran, A.B., & Cornes, C. (1991). Efficacy of interpersonal psychotherapy as a maintenance treatment of recurrent depression: Contributing factors. Archives of General Psychiatry, 48,1053-1059. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810360017002.

51. Wilfley, D.E., & Shore, A.L. (2015). Interpersonal psychotherapy. In J.D. Wright (Ed.), International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences (2nd Edition) (pp. 631-636). Elsevier.

52. Wurm, C., Robertson, M., & Rushton, P. (2008). Interpersonal psychotherapy: An overview. Psychotherapy in Australia, 14(3), 46-54.

53. Barlow, D.H., Farchione, T.J., Fairholme, C.P., Ellard, K.K., Boisseau, C.L., Allen, L.B., & Ehrenreich-May, J. (2011). The unified protocol for transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders: Therapist guide. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

54. Ehrenreich, J.T., Goldstein, C.M., Wright, L.R., & Barlow, D.H. (2009). Development of a Unified Protocol for the treatment of emotional disorders in youth. Child and Family Behavior Therapy, 31(1), 20-37. doi: 10.1080/07317100802701228

55. Johnston, L., Titov, N., Andrews, G., Spence, J., & Dear, B.F. (2011). A RCT of a transdiagnostic internet-delivered treatment for three anxiety disorders: Examination of support roles and disorder-specific outcomes. PLoS One, 6(11), e28079.

56. Titov, N., Dear, B.F., Johnston, L., Lorian, C., Zou, J., Wootton, B., Spence, J., McEvoy, P.M., & Rapee, R.M. (2013). Improving adherence and clinical outcomes in self-guided internet treatment for anxiety and depression: Randomised controlled trial. PLoS One, 8(7), e62873.

57. Rohde P. (2012). Applying transdiagnostic approaches to treatments with children and adolescents: Innovative models that are ready for more systematic evaluation. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 19(1), 83-86. doi:10.1016/j.cbpra.2011.06.006.

58. Bilek, E.L., & Ehrenreich-May, J. (2012). An open trial investigation of a transdiagnostic group treatment for children with anxiety and depressive symptoms. Behavior Therapy, 43(4), 887-897. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2012.04.007.

59. Weiss J.A. (2014). Transdiagnostic case conceptualization of emotional problems in youth with ASD: An emotion regulation approach. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 21(4), 331-350. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/cpsp.12084

60. Cohen, J.A., Mannarino, A.P., & Deblinger, E. (Eds.). (2012). Trauma-focused CBT for children and adolescents: Treatment applications. Guilford Press.

61. Shapiro, F. (2017). Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) therapy: Basic principles, protocols and procedures. (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

62. Shapiro F. (2014). The role of eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) therapy in medicine: Addressing the psychological and physical symptoms stemming from adverse life experiences. The Permanente journal, 18(1), 71-77. https://doi.org/10.7812/TPP/13-098

63. Hoover, D.W. (2015). The effects of psychological trauma on children with autism spectrum disorders: A research review. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 2(3), 287-299. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40489-015-0052-y

64. Stack, A., & Lucyshyn, J. (2019). Autism Spectrum Disorder and the experience of traumatic events: Review of the current literature to inform modifications to a treatment model for children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 49(4), 1613-1625. doi: 10.1007/s10803-018-3854-9.

65. Sizoo, B. & Lobregt, E. (2016). Treating trauma with EMDR in adults with autism spectrum disorders (ASD): A literature review. European Psychiatry, 33, S699. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2016.01.2081

66. Lobregt-van Buuren, E., Sizoo, B., Mevissen, L. & de Jongh A. (2019). Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) therapy as a feasible and potential effective treatment for adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) and a history of adverse events. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 49(1), 151-164. doi: 10.1007/s10803-018-3687-6.