Fakhri Shafai, Ph.D., M.Ed. Brain and Mind Institute, Western University

Moira Peña, BscOT, MOT, Occupational Therapist, Holland Bloorview Kids Rehabilitation Hospital

Elsbeth Dodman, Honours B.A. Autistic Self-advocate

8-Sensory-Systems-Toolkit-Worksheet

Chosen terminology: Throughout this toolbox we refer to "persons on the spectrum" or "Autistic persons". We have chosen this language based on the recommendations of one of this toolkit's authors, Elsbeth Dodman, an autistic self-advocate, and in agreement with recent research organization and journal guidelines. These terms encompass the previously used terms of individuals with autism, Asperger's, and Pervasive Developmental Disorder (PDD).

This toolbox also uses the terms hyper- and hyporeactivity instead of the previously used terms of hyper- or hyposensitivity. Research has shown that a person on the spectrum is not necessarily more sensitive to sensory input, but rather the way in which they react to that information is different. For instance, people on the spectrum who react strongly to bright lights do not have more receptors in their eyes. Similarly, someone who is constantly seeking tactile input isn't doing so because they have fewer nerve endings in their skin. It is not that the person is actually receiving more or less sensory information than others, but, rather, their reaction to the sensory input is different

Introduction to sensory processing differences

Sensory processing differences are a common issue for autistic children and often remain problematic into adulthood. Many people on the spectrum show challenges with balancing their reactions to incoming sensory input in at least one sensory area, but it is common to experience issues in multiple senses.

This toolkit is designed to provide autistic persons and their families with an introduction to the 8 sensory systems, questions to help determine the individual’s most impacted sensory systems, and to give an overview of strategies to try at home. Additional resources, including an overview of professional treatment options, are provided along with recommended reading and websites.

April is an 18-year-old Autistic woman who really hates sudden loud noises and has difficulty focusing on her surroundings in crowds. This makes going to the grocery store, mall, or outdoor events very difficult. For April, sudden loud noises are frightening and all consuming. April is often very tired and prone to emotional meltdowns by the end of a busy day.

Ben is an 8-year-old boy who has a very limited diet and has difficulty recognizing when he's hungry. He doesn't like the texture of most foods and doesn't find fruits or vegetables visually appealing. Because of Ben's restrictive diet he is often constipated and his pediatrician has confirmed that he is lacking the nutrients his growing body needs.

Sensory Systems

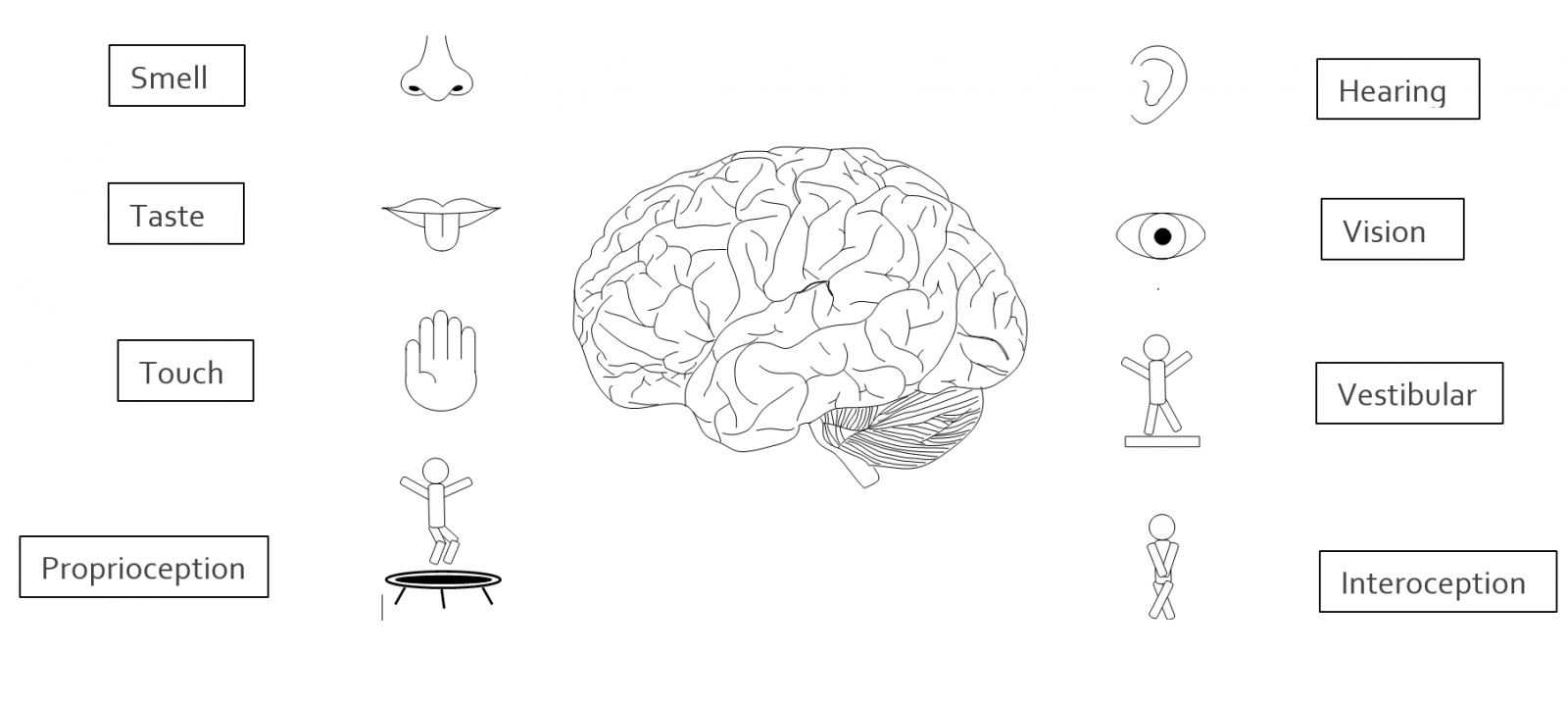

Most people are aware of the five sensory systems of vision, hearing, taste, smell, and touch, but there are three other major sensory systems that the brain is constantly processing as well: vestibular (balance and coordination), proprioception (body position and movement), and interoception (knowing what is happening inside our bodies, like hunger or thirst). Many autistic persons have difficulties in processing multiple sensory systems, although the specific senses affected and intensity of the issues can change throughout development and into adulthood.

Reacting to sensory information

We are all constantly receiving information from our senses throughout the day. This information is usually filtered by the brain so only the most important sensory information receives our attention. For instance, if someone is talking to you, your brain will usually focus your attention so that you are seeing their lips move and hearing the words they say instead of listening to a fly buzzing against the window. At another time in the day, you may have a hard time paying attention to what someone is saying because you are very hungry. In that case, your brain is focusing your attention on what is more important to the health of your body (food), rather than what another person is telling you. By focusing our attention only on the senses that matter at a particular time, our brain keeps us from becoming overwhelmed by sensory information.

How sensory information makes us adjust our behaviour

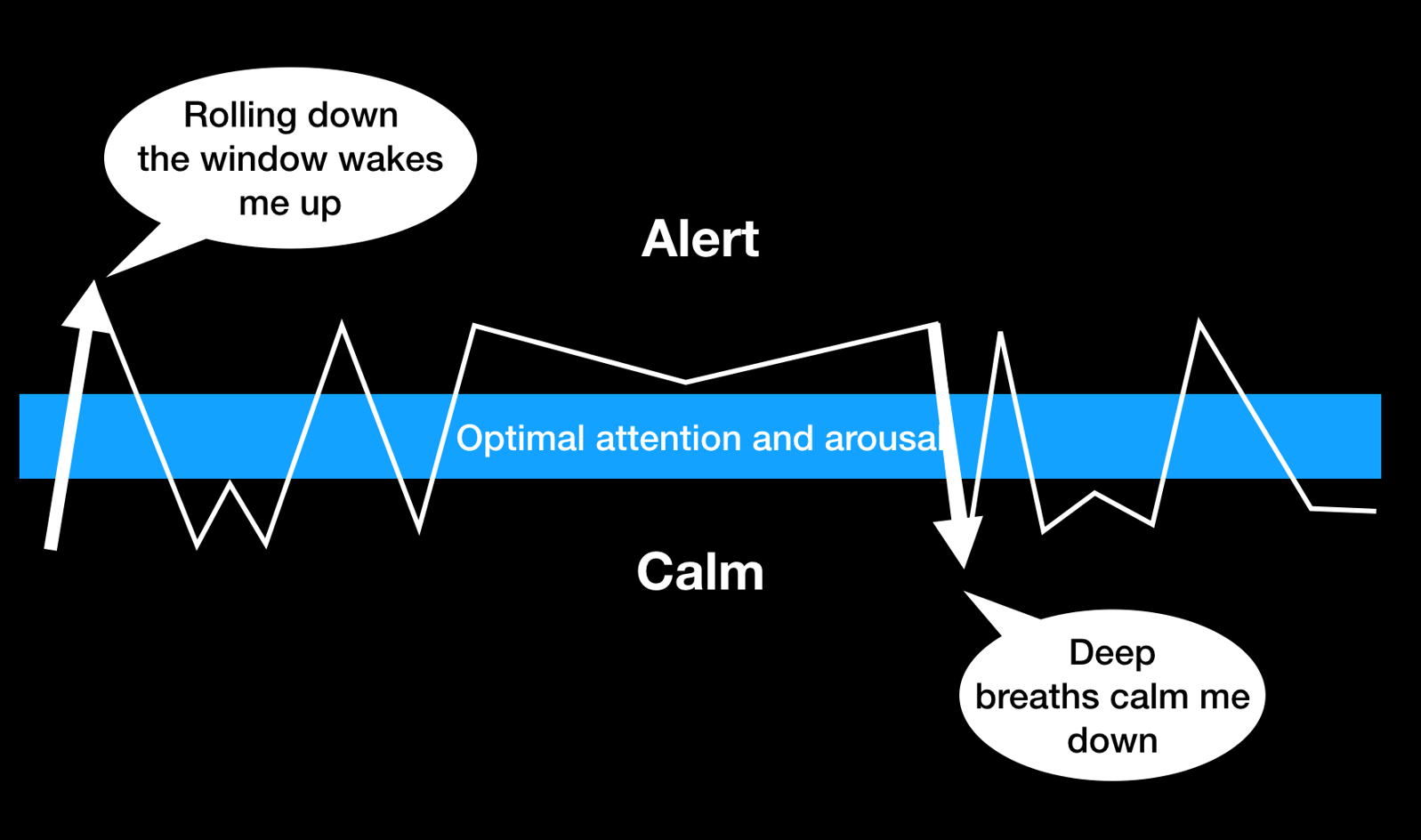

Our brains are constantly striving to keep us within an “optimal attention and arousal”, window, which describes when someone is able to stay calm and alert enough to manage their daily activities to the best of their abilities. Everyone moves above and below this optimal attention and arousal window throughout the day, and it is common to adjust our behaviour throughout the day in an attempt to get back to this optimal state. For instance, in the morning many people drink caffeine or roll down the window on their drive to work so that they can feel more awake. At other times in the day, a person may feel anxious because they have to give a big presentation and so they close their eyes and take deep breaths to make themselves feel more relaxed.

Hyperreactivity vs. Hyporeactivity

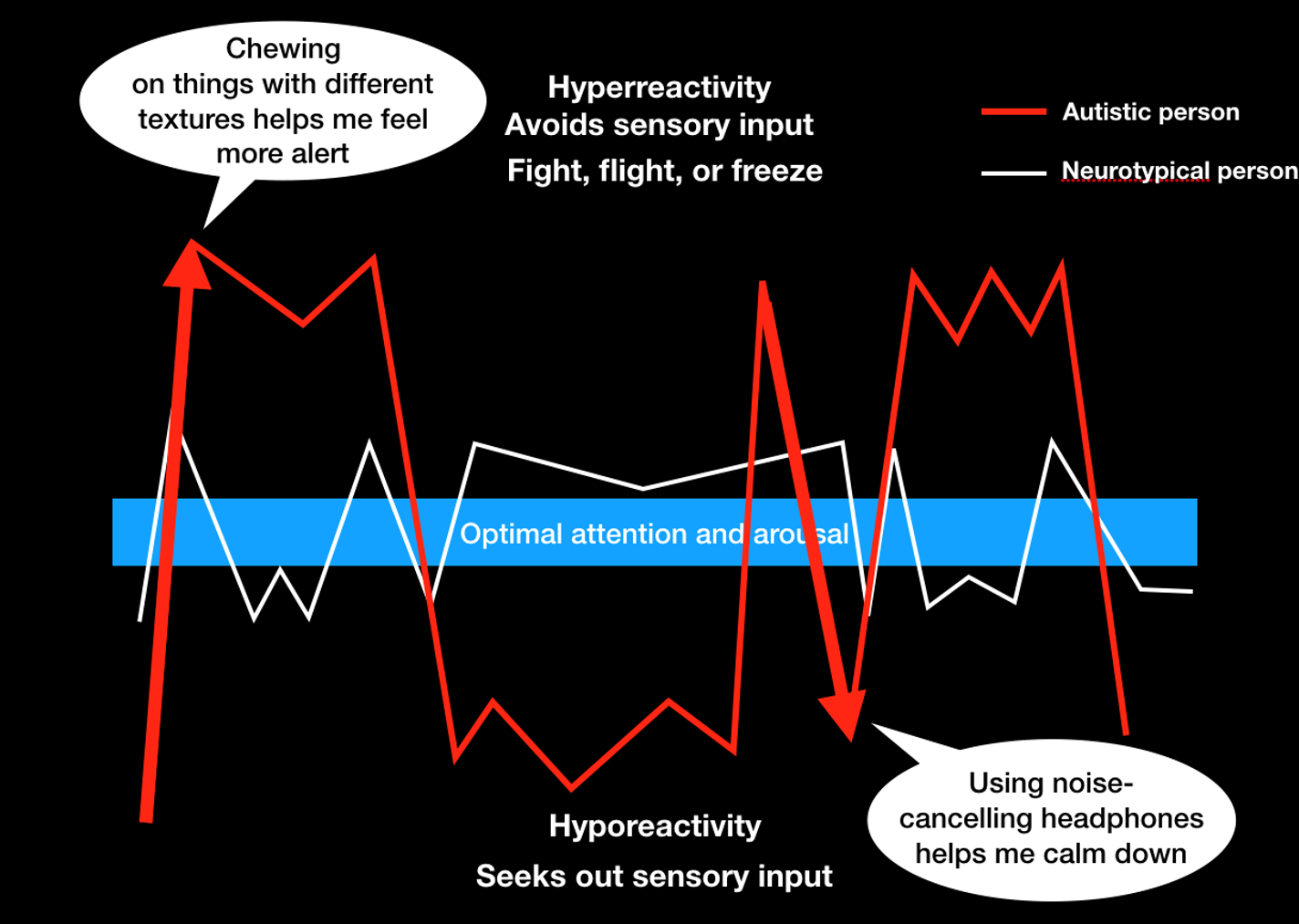

Extreme reactions to sensory information can be classified as either hyperreactive (being overwhelmed) or hyporeactive (not reacting to sensory input as one should). In both cases, the person is far from their “optimal attention and arousal” window, which means they are not feeling calm and alert.

April has trouble in crowds because the layers of sounds (people talking, laughing, shouting, music playing, etc.) all get the same priority for her attention, making it hard for her to tell what she’s supposed to focus on. She often needs to ‘escape’ when she is feeling overwhelmed in these situations and either leaves the event or tries to find a quiet place.

If a person’s brain is unable to filter out irrelevant sensory information, they can experience sensory overload and their nervous system will move towards the hyperreactivity direction. Being overwhelmed by sensory information can activate the nervous system to go into “fright, fight, or flight”. People who are experiencing sensory overload may respond by either freezing in place, acting angry or aggressive towards another person or object, or running away from the source of the sensory input.

Ben prefers tight hugs and strong touch. This input makes Ben feel grounded and helps him know where his body is in space. Ben is often bumping into objects and has trouble putting his coat on.

April loves to put things in her mouth –chewing on toys, pens, coins and straws. April chews on toys and other items to explore the world around her –she enjoys the different feelings and textures as they help soothe and calm her.

On the other hand, when a person is under-reacting or not reacting to sensory input as they should, they can move towards the hyporeactive direction. People with this sensory profile will respond by seeking out sensory input and you may see behaviours like listening to really loud music, chewing on clothing, non-edibles, or possibly some part of their body, or spinning in circles. Autistic persons tell us that they engage in these behaviours to help them feel calmer and more alert.

It is common for autistic persons to be at one extreme or the other at various times during the day. Being able to focus their attention on just one or two sensory systems can be difficult for persons on the spectrum. For instance, in the earlier example of someone talking, an autistic person may have trouble focusing on watching the speaker’s lips move or hearing their words because the fly buzzing against the window is getting as much of their attention. Like all of us, autistic persons will adjust their behaviours in an attempt to re-enter their “optimal attention and arousal” window. The major difference is that, sometimes, the behaviour they engage in may cause them to “overshoot” and move too far in the other direction .

Is it hyperreactivity or hyporeactivity: Becoming a sensory detective

It can be difficult to know if the behaviours you are seeing are due to the person on the spectrum being overwhelmed or not reacting enough to the sensory input. Some behaviours look similar (for example, chewing of clothing or non-edibles), can be a coping strategy for being over- or under-stimulated by a person’s surroundings.

This is where “becoming a sensory detective” can be helpful. Try to identify the time of day and observe the context immediately before and after the behaviour occurs. Does the behaviour usually start at the beginning of the day or towards the end? Did the autistic person become distressed after being in a loud, crowded place? Do they seem calmer after they engage in a sensory-seeking activity? If so, they were probably overwhelmed and frustrated by the sensory information and engaged in this behaviour to calm themselves down.

Alternatively, was the autistic person very calm before the behaviour and they seemed more alert afterwards? They were probably engaging in the behaviour to “feel something” and bring their attention and arousal up. By observing and taking careful notes, patterns can be unveiled which can give us information as to when it is best to intervene.

The neuroscience behind sensory differences in autism

While researchers have been studying differences in sensory processing for years, it was not until recent scientific advances in neuroimaging that we were able explore the structural differences in the brain. Many of these studies have found evidence that there is great variety in neuroanatomical differences between autistic persons. Despite this lack of consistency, some trends in neuroscience have begun to emerge:

- Extra connections in sensory areas: The sensory areas of persons on the spectrum may contain more synapses, or connections, between neurons. If these extra connections are sending messages all at once, then it may lead to the brain being overwhelmed with sensory input. This is thought to contribute to the ‘static’ that some Autistic persons describe when asked about their sensory experiences.

- Differences in connections between brain regions that are further away from each other: If the brain is spending energy maintaining extra connections, then there are fewer resources available to strengthen neural pathways connecting regions further away from each other. For instance, visual information is processed at the back of the brain. Motor planning, however, is located at the top of the brain. A weaker long-distance connection between these two regions may explain the ‘clumsiness’ that some persons on the spectrum experience. However, long-distance connections can also be stronger in some autistic persons. For instance, recent studies have found that some individuals have stronger connections between sensory areas and the thalamus, a structure that is responsible for relaying sensory signals to the rest of the brain.

- Differences in amygdala activity: The amygdala is associated with fear and anger responses. Differences in the strength of the connection between sensory areas and the amygdala may contribute to extreme responses to certain sensory input. Please see the ‘Self-regulation’ toolkit for more information about the amygdala’s role in meltdowns.

- Difficulty switching between brain processes: It can take longer for persons on the spectrum to switch from processing one sensory input to another or to process two or more senses at once. Being asked to rapidly switch attention (e.g. watching many moving objects at once) may contribute to being overwhelmed by sensory information.

Determining the autistic person's individual needs

At the end of this toolkit is a table titled ‘The 8 Sensory Systems’ that is a summary of the most important information for each sensory system. This document is separated from the rest of the toolkit to serve as a quick reference guide when trying to determine the sensory input that is causing a particular reaction. It includes a non-standardized checklist with examples of both hyper- and hyporeactivity responses in each sensory area. This checklist can be helpful for caregivers and clinicians to identify the specific sensory systems that are problematic for the autistic person. It can be used to inform the components of a ‘sensory diet’ or ‘sensory lifestyle’.

A ‘sensory diet’ or ‘sensory lifestyle’ is a group of sensory activities that are personalized for the individual with sensory differences and specifically designed to ensure that they are receiving the sensory input their bodies need every day. The purpose of the sensory diet is to enable the development of skills that will support arousal, attention, self-regulation, and balance a person’s sensory reactions. The last column of the table contains a list of possible sensory activities. It is important to note that the activities included in a sensory diet are not prescriptive, they are meant to be samples of a wide set of possible options that a parent can choose from with the child’s enthusiastic consent. Children will often tell us or show us what they need based on their actions – follow their lead.

April has a hard time with sudden loud noises because the noise is unexpected and she cannot prepare herself for it or know ‘this is how long it will last’. When loud noises do come –like an ambulance or fire alarm –she will scream and cover her ears to try and drown out the painful sounds. April may also try to run or tense up as she startles from the sudden loud noise. Even when the noise is gone, she can still be nervous and overly alert.

Examples of extreme auditory reactions

Every person on the spectrum has their own unique preferences for the types of auditory information they find to be pleasant or unpleasant. It can be difficult to determine what noise is triggering their reactions. When becoming a sensory detective to narrow down the options, it is helpful to note the reactions and list details about the context in which the reactions took place (for instance, running away when the school bell rings at recess).

| Hyperreactive auditory responses | Hyporeactive auditory responses |

| Covering ears around unpleasant noises (e.g. sirens) Running away from certain noises or loud settings (e.g. mall) Yelling at or trying to break the source of an unpleasant noise | Putting ear against a noise source (e.g. TV speaker) Creating loud noises (e.g. slamming doors repeatedly) Humming or yelling repeatedly |

Notice from the examples above that it is not always clear what is causing the behaviour. For instance, is the person trying to dismantle a clock because they don’t like the noise of the alarm (hyperreactive), OR are they trying to dismantle it because they want to create a loud noise and enjoy the sensory input of the plastic cracking (hyporeactive)? Is the person yelling because they are overwhelmed and trying to drown out the other sounds around them (hyperreactive), OR is the person yelling because they are under-stimulated and like hearing their voice at that volume (hyporeactive)? Carefully observing and taking notes about the situation can help when trying to identify patterns of what may be triggering the behaviour.

Issues with predictability: One of the most common complaints from autistic persons is that sometimes a noise can sound far away, and sometimes it can sound like it is right next to them. If a sound (for example, the school bell) is perceived differently each time, then the brain is not able to get used to that noise and it can lead to uncertainty and anxiety.

April helps herself avoid getting overwhelmed by wearing noise-canceling headphones in a crowd. When April gets home she gives herself a few hours to sit quietly on the computer or read by herself in her room to recharge after a long day to avoid meltdowns.

Visual sensory differences

Reactions to visual information are extremely varied in persons on the spectrum. Despite this variety, some patterns for different aspects of visual processing have emerged. Just like with the other sensory systems, many people on the spectrum fluctuate throughout the day between being overwhelmed or not reacting enough to the visual information around them.

While it is not true of everyone, many people on the spectrum experience differences in the way they process all visual information — from bright lights to colours, to objects in motion. There are patterns of both hyper- and hyporeactivity in reactions to many visual tasks (for example, being able to notice changes in colours).

Visual processing plays an important role in social functioning (for example, being able to tell when someone is angry), and a number of differences have been found in the ways that people on the spectrum process faces.

April cups her hands around her eyes when she wants to narrow her field of vision and focus on one thing at a time. By doing this, April helps cut down on some of the information she’s taking in.

Gabriella has difficulty with the florescent lights at school because the lights hurt her eyes and are too bright for her to concentrate. She has troubles copying the board notes in class –she finds the lighting makes it hard to focus on the board and her paper.

Examples of extreme visual reactions

Sensory seeking and sensory avoiding behaviours are common in response to visual information, and many times it is clear which sort of behaviour is being displayed just by noticing what the person does or does not pay attention to. Extreme avoidance is usually the result of being overwhelmed by one or more aspects of the visual information around. For instance, crying and running away at the end of movies may indicate that something about the credits moving down the screen is distressing for that person.

| Hyperreactive visual responses | Hyporeactive visual responses |

| Excessively shielding eyes around bright or fluorescent lights Refusing to enter rooms if they have too much on the walls Being upset when lots of things are moving around at once | Looking at things out of the corner of their eye Shining bright lights directly in their eyes Moving or flicking fingers in front of eyes |

Multiple eye-tracking studies have shown that autistic persons tend to spend less time looking at certain things (for example, faces) but can focus intensely on other types of visual information, for instance small details or patterns. Sometimes it is difficult to know if avoidance of looking at something directly is the result of sensory seeking or sensory avoiding behaviour. Are they avoiding looking at something because they find it unpleasant or overwhelming (hyperreactivity), OR are they looking at things out of the corner of their eye because they enjoy the visual sensory input coming from the periphery (hyporeactivity)? Looking at the context can help.

Issues with eye contact: People on the spectrum often spend less time looking at a person’s eyes, making it hard for them to know how others are feeling. For some autistic persons, avoiding looking at the eyes prevents them from becoming overwhelmed by the emotional information they convey. For others, it is difficult to interpret the eyes and instead they focus on the mouth to try and figure out how the person feels (e.g. are they smiling or not). Regardless of the root cause, eye avoidance is related to increased anxiety for autistic persons during social interactions.

April’s family has printed out and laminated picture cards of beakers which go from empty to full and April points to which beaker she’s at –when she points to one that’s very full it’s time to leave or find a quiet place. This is helpful so she doesn’t have to try and use her words when she is overwhelmed.

Gabriella will wear sunglasses in class if the teachers are not able to dim the lights for her or put tissue paper over the fluorescent lights to reduce the amount of light and flickering.

Tactile (touch) sensory differences

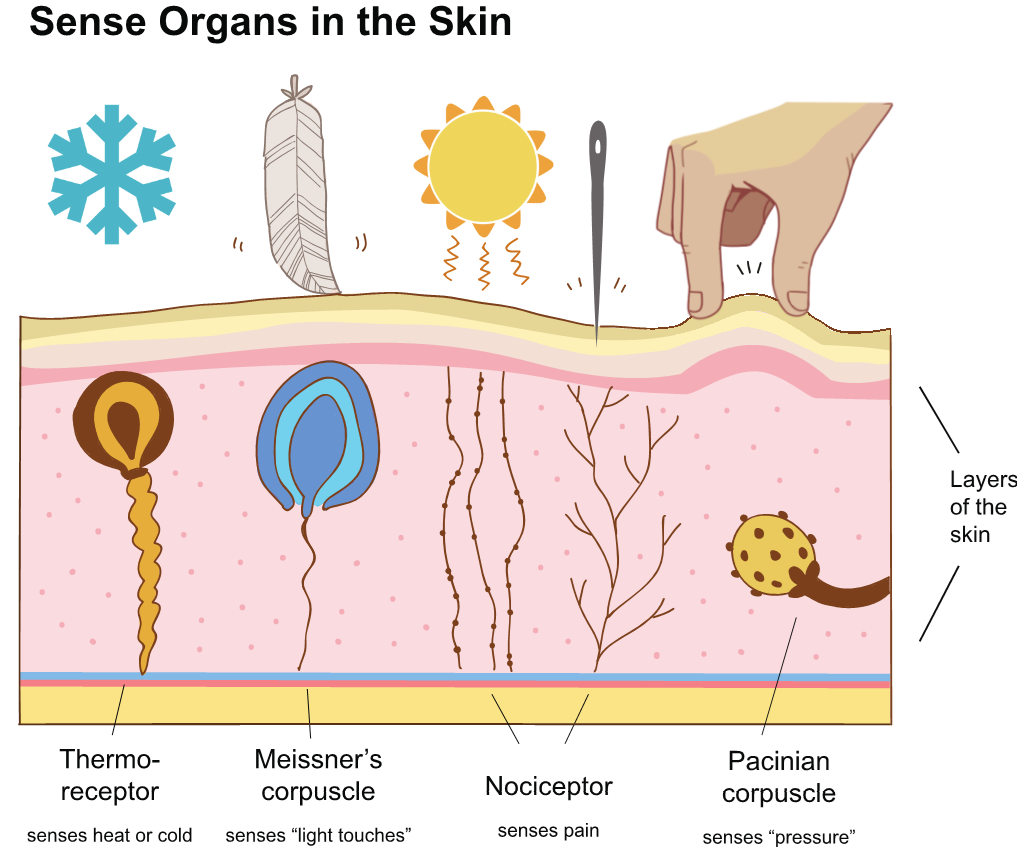

The tactile system, or sense of touch, allows us to feel textures, vibrations, temperature, and pain. It uses receptors in the skin and throughout the body to send information about what we have touched. These receptors provide information about the environment and the physical qualities of any object we touch (e.g. smoothness).

Despite being a single “sense”, our tactile system is complex and uses four different types of receptors to give us information about what we are touching. It is possible for someone to be outside the ‘optimal attention and arousal window’ by being hyperreactive in some aspects of touch (e.g. overreacts to a gentle touch) while being hyporeactive in another aspect of touch (e.g. doesn’t respond to touching something hot).

It is possible for people on the spectrum to fluctuate between hyper- and hyporeactive responses to different types of touch throughout the day or in specific situations (e.g. always reacts strongly to clothing tags).

Gabriella loves to run her hand along the walls of her home to feel the bumps. She also rubs her face against the rough fabrics to feel it scratch on her skin. Gabriella doesn’t like it when people brush up against her or lightly touch her, though. Light touch is painful and makes her feel on edge. This is especially true for clothing tags, which, for Gabriella, feels sharp and itchy.

Examples of extreme tactile reactions

The four major classes of receptors in the skin and body allow for us to interpret different aspects of our environment. Thermoreceptors respond to both heat and cold. Another type of receptor senses light touches, like that of a feather. There are two types of pain receptors, called nociceptors, one that responds to pain like sunburns, while the other responds to pain caused by things like needle pricks. The final class of touch receptors are deeper in the skin and respond to pressure, like being pinched by someone. Any one of these receptors can by hyperreactive or hyporeactive at various points during the day.

| Hyperreactive tactile behaviours | Hyporeactive tactile behaviours |

| Avoids physical touch and hugs Reacts strongly to wearing clothing with tags Dislikes or avoids brushing their teeth or hair | Constantly touches people or objects Unusual high pain tolerance Prefers to wear tighter and/or heavier clothing |

Issues with pain: One of the more perplexing aspects of tactile perception issues in people on the spectrum is that they can react to some forms of touch as if they were extremely painful while not reacting to other touch sensations that should be perceived as painful. For some people, the same information (e.g. a gentle touch on the arm) can fluctuate between being very painful sensory input, while, at other times, it can be barely noticed. This inconsistency can lead to anxiety as the person becomes unsure as to how the next touch sensation will feel.

Gabriella uses a small keychain animal with soft fur at school to help her sit quietly and not distract others. By occupying her hands, Gabriella finds she can stay seated longer allowing her to listen to the lesson. She now removes clothing tags before wearing any new clothes.

Olfactory (smell) sensory differences

The olfactory sensory system allows us to smell different odours and also plays a role in our ability to taste. We have multiple receptors in the nose that respond to various scents. Scents that are noxious, like ammonia, bind to certain receptors that respond by causing our nose to sting and eyes to water. Scents we enjoy are usually breathed in deeply, and when smelling food, allows us to better taste what we are about to eat.

Our sense of smell is also strongly tied to memories and emotions. Certain scents can become associated with a pleasant or negative experience, and when a person is exposed to that same smell, they will feel some of the same emotions they felt during that experience. For instance, if someone smells something that reminds them of a time that they felt nauseous, they may feel a wave of nausea every time they are exposed to that smell in the future.

For many people on the spectrum, strong reactions to scents can be on either side of the ‘optimal attention and arousal’ window, and it is common for individuals to show strong preferences or aversions to specific scents.

Yousef loves to smell things in his surroundings. He will stick his face in shoes left by the door, in the clean laundry basket and will go up to strange animals and put his face in their fur. Yousef loves to explore the world around him through scent and finds smells comforting. Yousef’s family doesn’t mind it at home but are worried that a strange dog or cat will bite Yousef –or that he might get into chemicals under the sink.

Examples of extreme olfactory reactions

Our sense of smell plays an important role in helping us taste our food. When scents bind to the receptors in our nostrils, a signal is sent to the brain and the smell will be interpreted as pleasurable or not. In the case of foods that we enjoy, the scent can cause our mouths to salivate in anticipation of eating the food. If we smell a food we do not like, for instance one that is rotting, we will often crinkle our nose and move away from the food. It is thought that our sense of smell is so connected with our sense of taste because it allowed our ancestors to determine whether they should reject a food before eating it so they could avoid getting sick.

| Hyperreactive olfactory behaviours | Hyporeactive olfactory behaviours |

| Refusing to enter rooms with strong odors (e.g. washrooms) Keeping away from people that are wearing perfume/cologne Becoming nauseous or refusing to eat foods with strong odors | Coming close to another person to smell them Smelling new toys or objects when they are introduced Seeking out strong scents (e.g. air fresheners, perfumes) |

It can be difficult to tease apart whether a person is avoiding a scent simply because they don’t like the scent itself, or if they are avoiding it because they have associated it with an unpleasant memory. In the case of just not liking the scent, it is usually best to learn avoidance strategies (e.g. holding one’s breath when walking through the perfume section at a store), or to provide regular access to scents they do enjoy so they can use it to mask the unpleasant scent (e.g. an aroma necklace).

If, however, the person is avoiding a scent because there is a negative memory associated with it, it may be helpful to try and expose them to only the smallest amounts of it while doing something else that they enjoy. This can help create new, positive associations with that scent. For example, if the person avoids the smell of a particular food because they once had a bad experience with it, try to open windows while it is cooking to minimize the scent while engaging in a preferred activity nearby.

Issues with adaptation: When someone walks into an area with a strong scent (e.g. the kitchen when food is cooking), it is common for them to notice the scent right away. As they spend more time in that area, the scent becomes less noticeable. This process is called ‘adaptation’ and it allows us to stop paying attention to things that are not changing rapidly, like the aroma in a room. Recent studies have shown that some persons on the spectrum do not adapt to scents quickly, meaning that they are just as noticeable as they were when they first walked into the room. This may lead to being overwhelmed and experiencing anxiety when going near areas with strong scents (e.g. kitchen, washroom).

Yousef’s family put some of his favorite aftershave on some of his plush toys so that he can carry those when he’s out of the house. They are working on teaching Yousef to ask to pet a dog or cat first before approaching it and have put special locks on the cupboards where the cleaning supplies are so that he can’t access them.

Gustatory (taste) sensory differences

The gustatory system allows us to taste by using chemical receptors located on the tongue and inside the mouth and throat. These receptors provide information about taste like whether a food is sweet, sour, bitter, salty, savory, or spicy. The gustatory system also provides information about the texture of foods, for instance whether they are soft or crunchy.

Eating challenges are a common complaint for persons on the spectrum. For some people, the taste of certain foods can be so overwhelming that they learn to avoid flavourful foods. For others, they perceive foods as being too bland and consistently choose foods with lots of at least one type of taste (e.g. add salt to foods that are already salty).

For some persons on the spectrum, it is not the taste of the food that they struggle with, but rather its texture. Some textures can be so overwhelming that they can cause the person to feel nauseous.

Ben doesn’t like the texture of most foods and doesn’t find fruits or vegetables visibly appealing. He cannot stand the slimy feel of mushy foods or the waxy, stringy texture of most vegetables. For Ben these textures are repulsive and not something he wants to put in his mouth.

Examples of extreme gustatory reactions

Some persons on the spectrum are described as “extreme picky” eaters and they struggle to try any new foods. It can be difficult to know what aspects of a particular food a person on the spectrum finds aversive, especially if they are young or not able to communicate their needs. Unfortunately, it can require a lot of trial and error to narrow down what is causing the aversion. Is it the flavour of the particular food? If so, does the food taste better with more/less salt, spices, etc.? Is the person on the spectrum more likely to eat the food if the texture is changed (e.g. mashed potatoes instead of French fries)? In general, starting with bland foods and slowly introducing more variety with some of the same properties as the food they are already eating (same colour, same temperature, same shape) can help expand the autistic person’s food repertoire.

| Hyperreactive gustatory behaviours | Hyporeactive gustatory behaviours |

| Eats only certain foods and resists trying new ones Reacts strongly to certain food textures (e.g. gagging) Tastes new foods only with the tip of the tongue | Chews or licks new objects Craves foods with strong flavours May keep foods in the cheeks (e.g. ‘pocketing’) |

Some persons on the spectrum constantly seek gustatory sensory input. These individuals will often put non-food objects in their mouth to explore their texture and taste. This need to put non-food objects in the mouth can be dangerous as objects can be swallowed or be laden with toxic chemicals (e.g. paint). Sometimes giving them regular access to other types of safe objects (like ‘chewlery’ or chewable jewelry) can help in preventing ingestion of unsafe materials.

Issues with meal time: When someone has an aversion to trying new foods, they can become very anxious before meals which may lead to challenging behaviours before or during meals. Placing additional expectations at meal time, for example, being asked to stay seated for an extended period of time, can lead to further acting out. This, in turn, leads to increased levels of anxiety.

Ben’s family makes fruit smoothies for Ben to cut down on the texture of what he’s eating. They continue to offer him new foods to try while speaking to a dietitian to make sure Ben is getting what he needs to thrive.

Interoceptive (inside body) sensory differences

Interoception, or knowing what is happening inside the body, is a sensory system that has been recently gaining attention for its connection to common issues in persons on the spectrum. The interoceptive sensory system gives information about whether a person is hungry or full, thirsty, or if they have a stomach ache or full bladder. Interoception issues may also influence sleep-wake cycles.

Many people on the spectrum describe hyporeactive responses in their interoceptive system and have trouble being able to quickly recognize that their body needs something. It can also be difficult for them to know when they are hot or cold. Some people struggle being able to tell if they have a rapid heartbeat or whether they are tense.

Hyperreactive reactions to interoceptive sensory information can also occur. For instance, a person can become hyper-aware of feeling pain or nausea when they are too full, so they respond by avoiding eating.

Not only does Ben have trouble knowing when he is hungry, but he can’t always tell when he’s in pain. Ben doesn’t mind pressing on bruises or picking at scabs. Ben is an active boy and his family is concerned that he might hurt himself while playing and not know to tell them.

Gabriella is a 13-year-0ld girl who loves to wear sweaters because they are heavy and comforting but cannot tell when it’s too hot to wear them. Because of this she is at risk of overheating in the summer months.

Examples of extreme interoception reactions

While some people on the spectrum can fluctuate between hyperreactive and hyporeactive reactions to interoceptive sensory information, it is common for individuals to stay consistently on one side of the “optimal attention and arousal” window for certain bodily functions. Unfortunately, constantly being on the hyperreactive or hyporeactive side of interoceptive sensory system can lead to long-term consequences for the person’s health. For instance, someone like Ben who is unable to recognize when he is hungry, may end up becoming underweight and malnourished.

| Hyperreactive interoceptive behaviours | Hyporeactive interoceptive behaviours |

| Avoids going outside in certain weather conditions Frequently uses the washroom to avoid having a full bladder Drinks excessive amounts of water to avoid being thirsty | Does not take off heavy clothing despite actively sweating Frequent accidents because they do not react to a full bladder Extremely high tolerance for pain, does not respond to injuries |

Issues with self-regulation: If someone is unable to tell when their heart is racing or that their muscles are tensed up, then they may not be able to recognize that they are building up anxiety levels in a particular situation. This makes it harder to recognize that there is a problem and engage in strategies before a meltdown occurs.

As described in examples listed above, some behaviours are direct opposites and it is easier to tell whether they are the result of hyper- or hyporeactive sensory responses (e.g. whether they are able to notice a full bladder). Other behaviours, though, make it difficult to know which aspect of the interoceptive system is causing the difficulty. For instance, does someone avoid eating because they don’t like the feeling of being full (hyperreactivity), OR are they not eating because they don’t notice hunger cues (hyporeactivity)? If the autistic person is unable to explain why they engage in certain behaviours, then it can be helpful to watch for changes in behaviour (e.g. when they initiate eating on their own) and keep track of the details surrounding it.

Issues with self-regulation: If someone is unable to tell when their heart is racing or that their muscles are tensed up, then they may not be able to recognize that they are building up anxiety levels in a particular situation. This makes it harder to recognize that there is a problem and engage in strategies before a meltdown occurs.

Ben’s family makes sure that meals and snacks are scheduled so he has prompts to eat regularly. They also pack snacks with them so that he has something to eat when they’re out. Ben’s family keeps an eye on any new bruises to make sure they’re healing. Ben has regular doctor’s appointments and Ben’s family have made sure to tell his family doctor that Ben doesn’t always react to pain.

Gabriella’s parents make sure that she has a water bottle with her and is drinking a lot during the summer to keep cool and that she stays in during peak hours when it’s hottest. Gabriella buys heavier t-shirts and sweaters with detachable sleeves to help her stay cool.

Vestibular (balance) sensory differences

The vestibular system is involved in perceiving movement and balance, with the primary organ of this sensory system being in the inner ear. Tilting our heads provides the brain with information about where the body is in relation to the pull of gravity. This system also uses information from the visual and proprioceptive systems and together they help with coordination, maintaining upright posture, and motor actions like climbing and jumping.

It is common for some people on the spectrum to struggle with not getting enough input from the vestibular system. Difficulties with sitting upright, bumping into objects, or the need to constantly move are all signs that the person may not be receiving enough sensory information from the vestibular system.

It also possible for people on the spectrum to struggle with receiving too much information from their vestibular system. This usually results in avoidance of activities that take their feet off the ground, like jumping or swinging, and avoiding certain types of transit as they can be prone to motion sickness.

Yousef is a 4-year-old boy who loves to jump and spin, especially when he is excited or happy. For Yousef, jumping and spinning is a fun way to express his emotions, which sometimes feel too big for his body to contain. He loves to feel his body in motion and climbs and jumps on the furniture at home or at school.

Examples of extreme vestibular reactions

Young children on the spectrum are often described as being either cautious or fearless with their body movements. Some are hesitant to make big movements and prefer to hold onto handrails or steady themselves against walls when walking. Others move recklessly and may jump from high places without worrying about personal safety. The tendency to move between sensory seeking and avoidance can change during development, with the most extreme behaviours usually occurring early in childhood.

| Hyperreactive vestibular behaviors | Hyporeactive vestibular behaviors |

| Refuses to go on swings or most playground equipment Regularly gets motion sickness quickly Has trouble changing directions quickly when walking | Spins in circles for long periods of time without getting dizzy Enjoys climbing and jumping without fear of injury Often rocks back and forth and has trouble sitting still |

In general, persons seeking vestibular input will move as much as possible and enjoy the sensory experience of quick, large motor actions (like jumping or falling from a far distance). People who try to avoid vestibular input will move more slowly, especially on uneven surfaces (for instance, a hiking trail). Rocking back and forth, for example, can be viewed as a sensory seeking behavior resulting from hyporeactivity to vestibular input. However, autistic persons may also engage in rocking behaviours to calm themselves when overwhelmed by sensory information as the linear repetitive movement can be soothing. It is important to look at the context of the situation when trying to determine whether a person is rocking because they are over- or under stimulated. When the autistic person is unable to communicate why they avoid or seek out vestibular-based experiences, it can be helpful to take note of what is happening before, during, and after the behavior takes place.

Issues with movement: Regardless of whether someone seeks or avoids input from the vestibular system, being at either extreme can impact their ability to move in a smooth and coordinated way. When balance is off due to either too much or not enough feedback from the vestibular system, it makes it hard for the brain to establish consistency, which can lead to increased anxiety levels.

Yousef’s family got a small indoor trampoline for Yousef to bounce on to replace his jumping on the furniture. At home and at daycare he sits on a moveable cushion to help him remain seated and still give him room to move. Yousef is now enrolled in a toddler gym class so that he has a chance to be active with other children.

Proprioception (body awareness) sensory differences

The proprioception sensory system takes in information from the muscles, joints, and skin during movement in order to provide information about where each body part is in relation to the rest of the body. It is often described as the ability to “know where your body is in space.”

A functioning proprioceptive system will allow someone to put on a backpack or get dressed without looking at their body parts as they move. Proprioception also enables people to control how loosely or tightly they hold an item. For instance, knowing how much pressure to use when writing with a pencil or how hard to throw a ball.

Not only does proprioception allow us to know where our body is while moving, but it also gives us information about the world around us. This system provides the feedback we need to know if we are walking on something hard like pavement or something soft like grass, even if we have our shoes on. The proprioceptive system also relies on vestibular input to help maintain balance when moving.

Ben prefers tight hugs and strong touch. It makes Ben feel grounded and helps him know where his body is in space. Ben is often running into objects and has trouble putting his coat on.

Examples of extreme proprioceptive reactions

It is not common for individuals on the spectrum to be overwhelmed by proprioceptive information. This makes sense as it is difficult to be too in-touch with where your body is and what is happening around it. In fact, activities like mindfulness meditation or yoga seek to better connect you to your body in the moment for this very reason. Being ‘body aware’ is generally considered a good thing for our brains and can help us relax.

| Hyperreactive proprioceptive behaviours | Hyporeactive proprioceptive behaviours |

| It is unusual to be overwhelmed by proprioceptive information | Needs to look at their arms when putting on a jacket Likes to do hard ‘high-5s’ Slouches at desk or falls out of their chair |

Most reactions to proprioceptive information in people on the spectrum are due to the person wanting more sensory input, not less. Sensory seeking behaviours are common and sometimes include a reliance on other sensory systems to help. For instance, people who have trouble knowing where their bodies are and how to move a body part will often look to try and give themselves more information. Otherwise, extreme actions, like stomping ones’ feet, help to provide additional feedback for the body to know where it is in relation to the environment around it .

Issues with pressure: Many people on the spectrum prefer different forms of pressure, whether from heavier clothing or from physical activities that increase muscle effort. These individuals are not getting the sensory input that they need, and so engage in behaviours to help them move to the ‘optimal attention and arousal’ window. When they do not have the ability to engage in these activities, it can cause them to feel disconnected from their bodies, which can lead to an increase in anxiety.

Ben asks a trusted family member to give him a big hug to help him feel anchored. Ben’s family organizes their home so that Ben has lots of room to move in and put a mirror up in the front hall for Ben to guide himself as he puts his coat on.

Multisensory differences

People on the spectrum experience differences in the way they process sensory information and also in the way that sensory information gets combined in the brain. The term ‘multisensory integration’ refers to two or more senses that are perceived as a single event. For instance, when a person is talking, we combine the visual information of their lips moving with the sound of their words. In certain situations, like in a crowded coffee shop, it can be helpful to focus our attention more on the lips of the person who is talking so we can better put that information together.

But what if this information isn’t combined correctly? If you have watched TV when the sound is not in sync with the video, you will likely notice and become irritated by it. This asynchrony can make it difficult to concentrate on the video and many people will change the channel or try to reload the video instead.

Research has shown that some persons on the spectrum don’t always integrate information from their visual and auditory sensory systems. For some individuals, the words they hear and what they see don’t match up. It can be more confusing for them to try and look at a person and listen to what they are saying. This difficulty may contribute to the tendency to look away from another person’s face because the two sources of information can be more confusing than helpful.

Examples of multisensory integration issues

It can be difficult to know whether certain behaviours are the result of issues with one sense or in the way the senses combine and work together. For instance, is a person frequently nauseous because they are reacting to strong odors (olfactory system) or because they have balance issues (vestibular system)? OR do they only feel nauseous if there are strong odors and they are in the car (multisensory)? If someone is struggling being in a big crowd, is it because they are overwhelmed by seeing all the people moving at once (visual system), hearing all the noises at once (auditory system), or because people are bumping into them as they walk past (tactile)? OR will they only respond that way if all three sensory inputs are taking place at the same time? To help tease apart the source of the reaction, it is helpful to see how the person responds when only one of the senses is being tested. For instance, will the person still have a strong reaction if they are standing to the side of a crowded area while wearing noise-canceling headphones? If not, then it probably isn’t the visual information that is causing their reaction. This can take time and require careful observations, but it is possible to narrow down the causes of the reaction.

Anxiety Issues and Sensory Differences

Each of the sensory systems discussed in this toolbox has a blue box that describes how challenges with sensory processing can be associated with anxiety. For many people on the spectrum who have issues with processing input from more than one sensory system, situations where multiple sensory inputs need to be processed at the same time can lead to increased levels of anxiety. For instance, if someone is overwhelmed by visual information and reacts strongly to scents, being in a food court in a mall may be more anxiety-inducing than processing either sensory input individually.

As previously described under the interoceptive sensory system, people who struggle to recognize the signals coming from inside their body (like increased heart rate, tensing of muscles, or stomach aches, etc.) may not notice when they are becoming more anxious. This can make it difficult to leave the situation in time before the anxiety reaches a critical level and a sensory meltdown ensues.

It is possible to improve sensory awareness in the interoceptive system and develop skills to mediate anxiety symptoms before they become overwhelming. For more information, please see our ‘Self-regulation’ toolkit.

Lead Photo by Elia Pellegrini on Unsplash