What kinds of feeding challenges do children and youth on the autism spectrum experience?

Picky eating, also referred in the research literature as ‘food selectivity’, ‘high frequency of single food intake’ and/or ‘limited food repertoire’, is the most commonly reported feeding problem in children and youth on the autism spectrum[3, 6]. Autistic children may have a limited intake of fruits and vegetables[7], and milk and other dairy products[8, 9]. They may also become highly selective and eat too much of specific calorie-dense foods, particularly those high in fat and sugar[1]. Other behaviours such as neophobia (fear of new foods) and pica (eating non-edible foods) are also common[10].

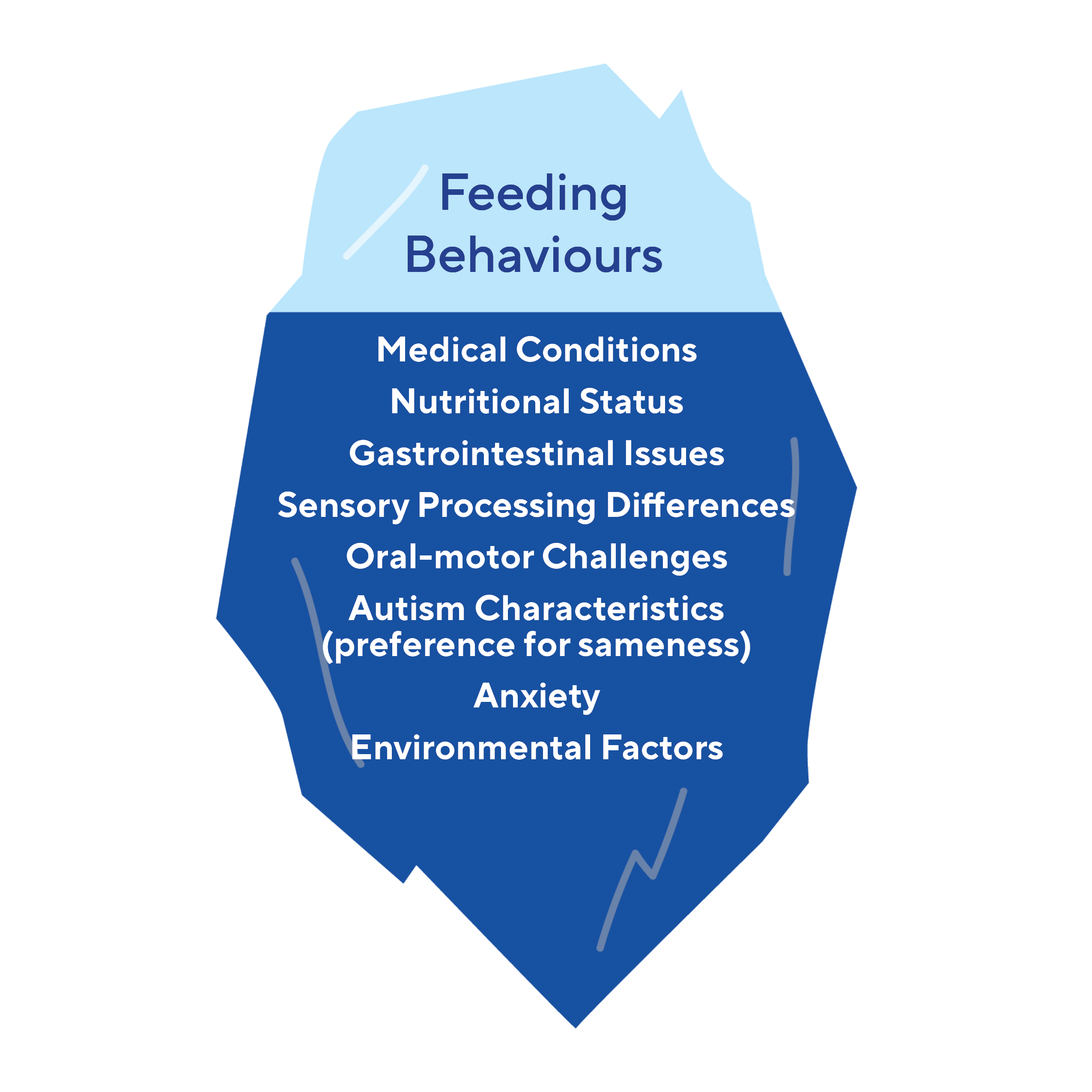

What are the reasons that cause feeding difficulties for persons on the autism spectrum?

There are many different potential causes for feeding challenges which include: medical conditions, the child’s nutritional status, gastro-intestinal issues, sensory processing differences, oral motor challenges, autistic characteristics such as a preference for sameness, anxiety, and environmental factors. Due to the multifactorial nature of feeding challenges, it may be helpful to conceptualize the observable feeding behaviour as the ‘tip of the iceberg’ with an understanding that there may be many factors contributing to the ‘why’ of the behaviour that are hidden from view.

Caleb is a teen who loves to get a sense of the world around him by putting things in his mouth. Sometimes this means he winds up swallowing objects that shouldn’t be eaten, like small toys which may become stuck in his GI track.

Caleb can’t always tell when the is hungry and can put off eating until he is shaking and jittery. Caleb’s family is careful of keeping small toys out of his reach and taking snacks with him when they go out so Caleb doesn’t crash. Keeping regularly scheduled meals can also help Caleb know when it’s time to eat.

Medical Conditions

It is important to screen and rule out underlying medical conditions that may be causing pain or impacting food consumption or compounding selectivity issues. Children and youth on the autism spectrum may be unable to communicate that they are in pain or uncomfortable either through words or gestures. They may also not be able to accurately identify their body’s internal signals of pain or overall discomfort that may indicate dental issues, acid reflux, chronic constipation and other gastro intestinal issues, food allergies, food intolerances, and other inflammatory diseases. Some studies have also found that food selectivity can be influenced by past traumatic experiences with a particular food[5]. Also, many medications have side effects that directly alter a person’s appetite. It is therefore best to enlist the help of a primary care doctor if any of these concerns or medical conditions are present or suspected.

Nutritional Status

Prior to implementing any feeding strategies or recommendations, it is also helpful to consult with a qualified health care professional to confirm that the person on the autism spectrum is nutritionally stable. Nutritional stability means that the child is both receiving proper nutrition and hydration from food and drinks and maintaining a healthy weight/height ratio.

Pica is a condition that involves eating non-food items and can be related to nutritional deficiencies[11]. While it is common for young infants and toddlers to put random objects in their mouths, these actions are defined as pica when there is chronic swallowing of harmful substances. Pica behaviours may be caused by nutrient deficiencies that produce craving of specific non-food items, even if that non-food item does not contain the missing nutrient[12]. For instance, if a person is low in iron, they may eat clay, despite the fact that consuming clay can make iron deficiency worse. Pica behaviour may also be compounded by seeking of sensory qualities such as specific textures or the tastes of the non-food objects[13]. Pica is often associated with intellectual disability, developmental delays, and/or other co-occurring mental health conditions[14]. It is important to address pica behaviours given the health concerns associated with pica, including an increased exposure to germs, likelihood of choking, ingesting harmful or life-threatening substances or objects, and an increased need for the surgical removal of objects[11]. While some individuals outgrow pica-related behaviours, some will require constant observation and consultation with a trained specialist. Once again, a primary care doctor or another qualified health care professional may refer the family to an appropriate specialist or program.

Gastrointestinal Issues

Gastrointestinal (GI) issues are one of the most commonly reported symptoms of discomfort for individuals on the autism spectrum. Studies have indicated that up to 82% of persons on the autism spectrum experience GI issues[15]. The most commonly reported GI issues include diarrhea, constipation, abdominal pain, and gastroesophageal reflux, commonly known as ‘heartburn’[15]. Additionally, rates of inflammatory bowel disease are higher in the autism population[16]. As It can be difficult for some to communicate their GI discomfort, especially if they are non-speaking, caregivers and medical professionals should monitor for behaviours that may indicate GI distress. In some cases, food refusal may be less about disliking the food and more about trying to avoid later GI discomfort. Constipation in particular can be attributed to a lack of a varied diet that includes fibre and other nutrients. Behaviours that can signal GI distress can include holding the abdomen, facial grimacing, as well as mouthing behaviours such as frequent clearing of throat, swallowing, or tics, sighing or whining, screaming, moaning, and/or groaning[16].

While it is not currently known exactly what causes GI issues, there is evidence to suggest that there is an altered microbiome of gut bacteria in the GI tract that may make it more difficult for some persons on the autism spectrum to properly digest food and absorb nutrients[16]. This has led some families to pursue under-studied therapies that claim to change the microbiome, including fecal transplants. While there have been some promising results in studies with rodents, there is little evidence that fecal transplants are helpful for autistic children and adults[17]. The few studies that have explored this issue have had very small sample sizes making it difficult to conclude that any of the results can be applied to the autistic population in general. At this time, we are unaware of any studies evaluating fecal transplants in individuals on autism spectrum that have used double-blind, placebo-controlled trials, which are considered the gold standard of clinical research and would be required before medical professionals can reliably prescribe such treatments[18]. As such, there is no conclusive evidence that such extreme measures produce meaningful, long-term changes in GI symptoms or alter severity of autism symptoms.

Some families have tried giving their child larger amounts of probiotics in the hopes that they can alter the gut microbiome. While probiotics can be found in many foods (e.g. yogurt) and may provide relief for some individuals, it is important to note that the overuse of probiotics can lead to additional GI discomfort, including causing diarrhea and bloating[17]. Therefore, probiotic use should be monitored by a medical professional to ensure that a healthy gut balance is being maintained. A nutritionist, dietitian and/or GI specialist can also help families identify the varied causes of GI issues and can best inform families as to best steps to take to improve a person’s overall gastro-intestinal comfort.

Johnny is 10 and has a very selective diet as well as some difficulties chewing. He typically eats chicken fingers at most of his meals because the taste and texture is familiar, even when he orders them at different restaurants. Apples may look nice to Johnny when he sees them at the store but the texture when he tries to bite into and chew them feels absolutely terrible. Each apple can taste different; some sweeter or more tart than another.

Sensory Processing Differences

Sensory processing differences can lead to the avoidance of particular foods due to the sensory qualities of that food. It may be challenging for individuals on the autism spectrum to manage sensory aspects such as food texture, visual appearance, temperature sounds of foods, taste, and smell[5, 19]. Many autistic adults have reported that food texture is the main factor that determines whether they will accept a particular food or not[7]. While whole grains, lean protein, fresh fruits, and vegetables are high in nutrients, they are also often characterized by intense flavours and textures, which explains why some autistic individuals may experience difficulties with accepting them into their diet[7] . Challenges with interoceptive awareness, the sensory system involved in the accurate recognition of the cues of being hungry or full, can also contribute to feeding challenges. A person may not be able to correctly identify whether they are hungry or full which can then lead to either under or over-eating.

Some sensory-based strategies that have been found to be helpful in supporting children on the autism spectrum expand the number of foods that they are eating include the following:

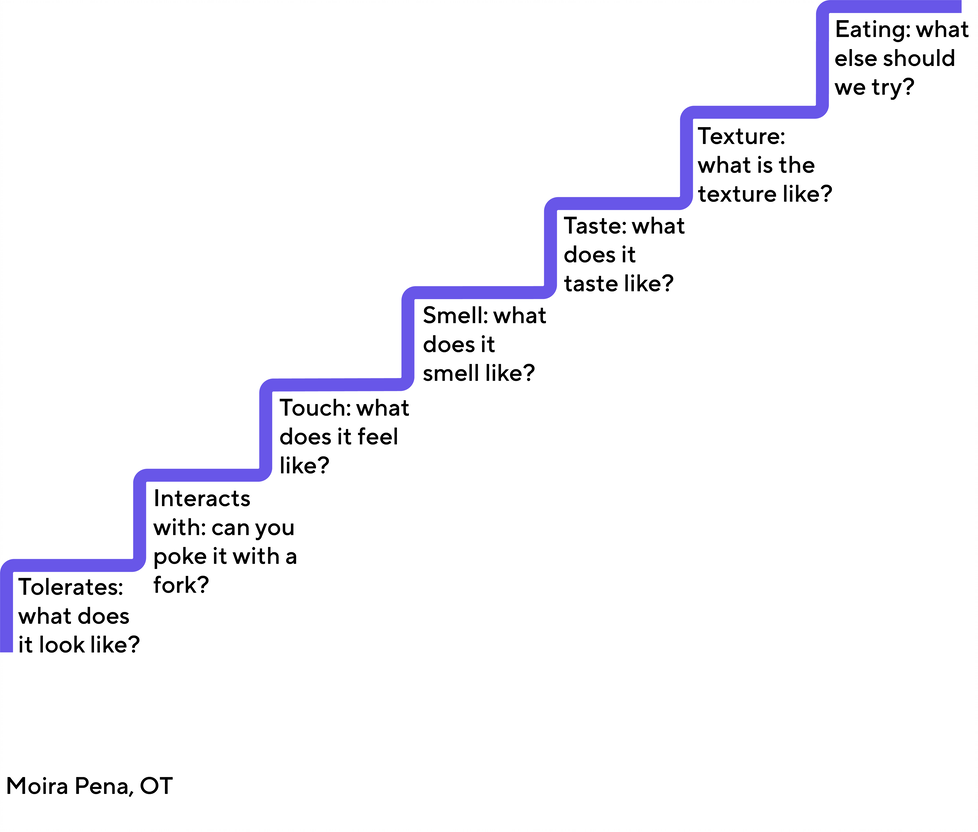

Building acceptance to new foods through gradual exposure: Children and youth on the autism spectrum may experience sensory sensitivities to food as distressing and even painful. With this in mind, it is helpful to use the principles of gradual exposure to help a person become increasingly more comfortable with the sensory qualities of food.

Take for example, “Johnny” who is not yet able to accept apples into his diet. First, we need to work on getting him comfortable with just looking at an apple in front of him for a few minutes. We would then move on to touching the apple with a fork, then with a napkin, then with his fingers, and so on until he is able to accept the feeling of the apple texture near and in his mouth. Play-based language such as, “I challenge you to place the apple on your cheek for 30 seconds,” may help to keep a child engaged and motivated through the process. Progressing in small, incremental steps towards eating a food by starting with small bites and then gradually increasing the size of the bite for example, will help a child in becoming more comfortable with the sensory properties of a food. If the child is able to express themselves then asking the questions below and having conversations about them might also be helpful in motivating the child to try new foods.

Encourage your child to explore, play and get messy with food: Children learn through play, and this includes playing with food. This dovetails nicely with the principle of “gradual exposure” described above. Encourage your child to interact with food through exploration with all of their senses. Talk about the look, temperature, and feel of foods. Think of it as “food school,” and reserve some time each week to engage in food learning through play. Your child may or may not eat the foods but exposure is important in ensuring that they continue to explore new foods. The idea is to build a foundation that allows greater comfort with foods which will then help your child to expand their food repertoire. Make the experience fun! Use interesting and playful low-cost utensils to help motivate the child to engage with the food!

Photo by Hannah Tasker on Unsplash

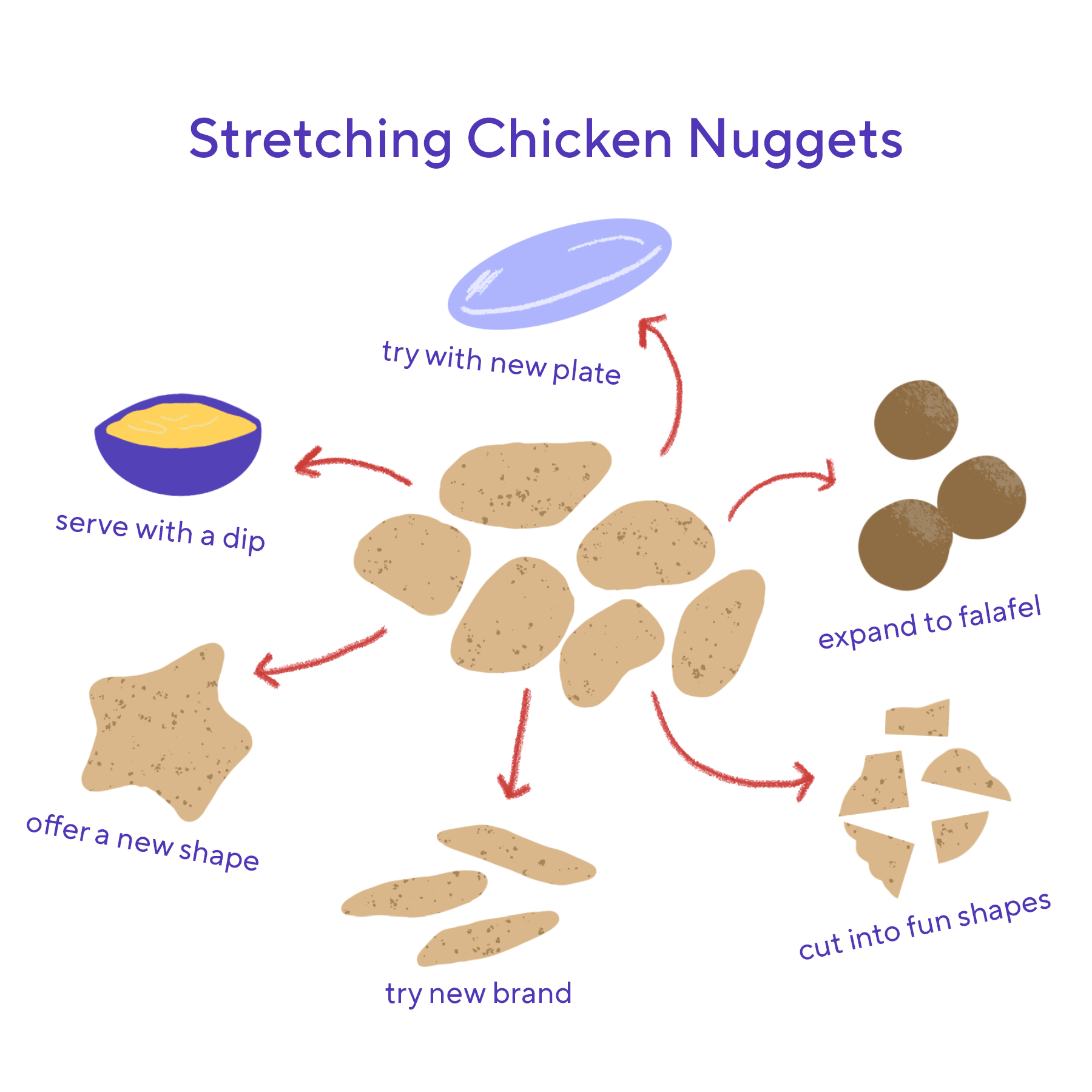

- Expand what your child already eats: Let’s say that a child’s favorite food is chicken fingers. You can start “stretching” their food acceptance by offering the same chicken finger but first cutting it in half, to then cutting it in quarters to then moving on a different brand of chicken finger to then progressing to trying a different shape of chicken finger. Eventually, you can introduce a dipping sauce such as ketchup or hummus, and then move on to a food that is somewhat similar to breaded chicken fingers in appearance, such as fish sticks or falafels. The idea is to offer a food that remains familiar looking while building tolerance to small and incremental changes. A change from chicken fingers to non-breaded chicken may initially be difficult simply because it looks too different.

Title: Stretching Chicken fingers

Scan for environmental sensory triggers: Strive to eliminate or tone down known environmental sensory triggers such as fluorescent lights, noises, or strong smells. This may mean removing the garbage can from the kitchen or any other eating areas prior to meals, ensuring that the child is sitting beside someone who is not a loud chewer, or perhaps dimming the lights during mealtimes.

Oral-Motor Differences:

Oral-motor challenges involve feeding challenges that arise from anatomical differences in the physical structure of the mouth and teeth (such as cleft lip and palate, tongue tie, etc.) as well as delayed oral motor skills (poor tongue lateralization, delayed chewing skills and/or poor lip closure). Many children with oral-motor issues do not instinctively learn how to chew solid food. To understand these challenges, it may be helpful to consider the muscle skills involved.

To chew food properly – particularly meat, vegetables, and fruit – a person needs to use what we call rotary chewing. This motion involves moving food around from the middle of the mouth to the back molars and then back to the middle of the mouth. In addition, rotary chewing requires one to move the tongue from one side of the mouth to the other. We call this skill “tongue lateralization.”

Some signs or that may indicate oral-motor challenges include:

- Excessive drooling

- Poor speech (forming the sounds)

- Gagging/choking/vomiting

- Open mouth when at rest

- Difficulty blowing bubbles/candles

- Difficulty sucking through a straw

- Taking a long time to chew

- Placing fingers inside the mouth to remove or insert food

- Swallowing foods whole

- Refusing unpeeled fruits

If oral-motor challenges are suspected, it is important to have your child assessed by a health care professional. This could be a speech-language pathologist or an occupational therapist with experience in feeding who can then determine if the child can eat solid foods safely. Introducing foods that are beyond the child’s ability to safely manage them presents a choking hazard. It’s extremely important to avoid introducing solid foods until a specialist has determined what level of solid food – if any – your child can manage safely. Also, a thorough assessment is vital for identifying underlying factors that may be contributing to the child’s challenges with chewing. It is important to keep in mind that oral motor challenges can present a lot like sensory processing challenges so it is important to be able to distinguish between the two. Once it has been determined that it is safe for the child to begin eating solid foods, here are some general strategies to try – if at all possible, under the guidance of a feeding therapist:

* Thicken purees. Experiment by adding corn starch or powdered baby cereal to the purees. The goal is to make the puree thicker, not chunkier. This will gradually increase the muscle work involved in eating them.

* Try various types of soft foods. Encourage child to try different foods that are already pureed to some degree such as mashed potatoes and apple sauce. The next step would be to try foods that are solid but still soft. Examples include soft cheeses, scrambled egg and soft fruits such as bananas.

* Model how to bite off small pieces. Rather than placing small pieces of food in your child’s mouth, show him how to bite a small piece from a whole piece of food such as taking a small bite from a French-fry.

* Model how to chew. Have your child watch where the food is going in your mouth as you chew. Show your child that you are chewing on your back molars. Try over-exaggerating the chewing motion at first, and ask your child to imitate you.

Autistic Characteristics (preference for sameness)

It is also helpful to keep in mind that feeding challenges may be related to autistic characteristics such as a preference for sameness, which may predispose a person to accept a lower variety of foods. A recent study found that non-autistic young adults with higher autistic-like characteristics also exhibited lower food variety and diet quality in childhood[20].

Sarah experiences anxiety around eating dinner; she becomes afraid of choking to the point of needing to spit out food or under eating to escape that fear. Sarah knows what she’s experiencing is anxiety because she can eat breakfast, snacks and lunch without a problem. This is frustrating for both Sarah and her family because she may like the food that’s on the table but her fear is stopping her from enjoying it.

Sarah tends to pack her cheeks as she eats and at dinner this can play into her dinner-time anxiety as she may feel she has too much in her mouth and needs to spit out food. Sarah is trying to work through her anxiety by taking meals one bite at a time, using distractions like a tablet or stepping away and coming back to the table once her anxiety has calmed. Sarah and her family are also working with a social worker and psychiatrist about her anxiety and how to manage it.

Anxiety

Associated mental health conditions such as anxiety may also play a role in feeding challenges. Approximately 50 to 79% of children and youth on the autism spectrum experience high rates of anxiety[21]. Some children on the autism spectrum experience anxiety as mealtimes approaches due to the underlying causes already discussed. Inadvertently, families can make the anxiety worse by trying to coerce a child to eat, setting up a pattern of mealtime stress. Anxiety shuts down hunger in a powerful way by putting the child in a biological state of ‘fight or flight’. This state causes a racing heart and tight stomach muscles, meaning the child will not feel comfortable enough during mealtimes to be able to try new foods. To reverse this pattern, it is helpful for parents to spend a few minutes helping the child relax before mealtimes. One way to do this is to spend five minutes practicing deep breathing together. This can be as simple as slowly and deeply inhaling for a count of four, then slowly and fully exhaling for a count of seven or eight. Alternatively, blowing pinwheels, bubbles or even a wind instrument such as a recorder or harmonica may be helpful in helping release anxiety. Or, you might use those five minutes to engage your child in a calming deep pressure activity, such as a pushing hands against the wall (have your child lean in with his or her full weight), completing a fun ‘tug of war’ with a towel, or having your child push the palms of his or her hands against yours for a few seconds.

"Forever blowing bubbles" by The 5th Ape is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Environmental Factors:

Lastly, it is helpful to determine if environmental factors may be contributing to a child’s feeding challenges. These environmental factors can be:

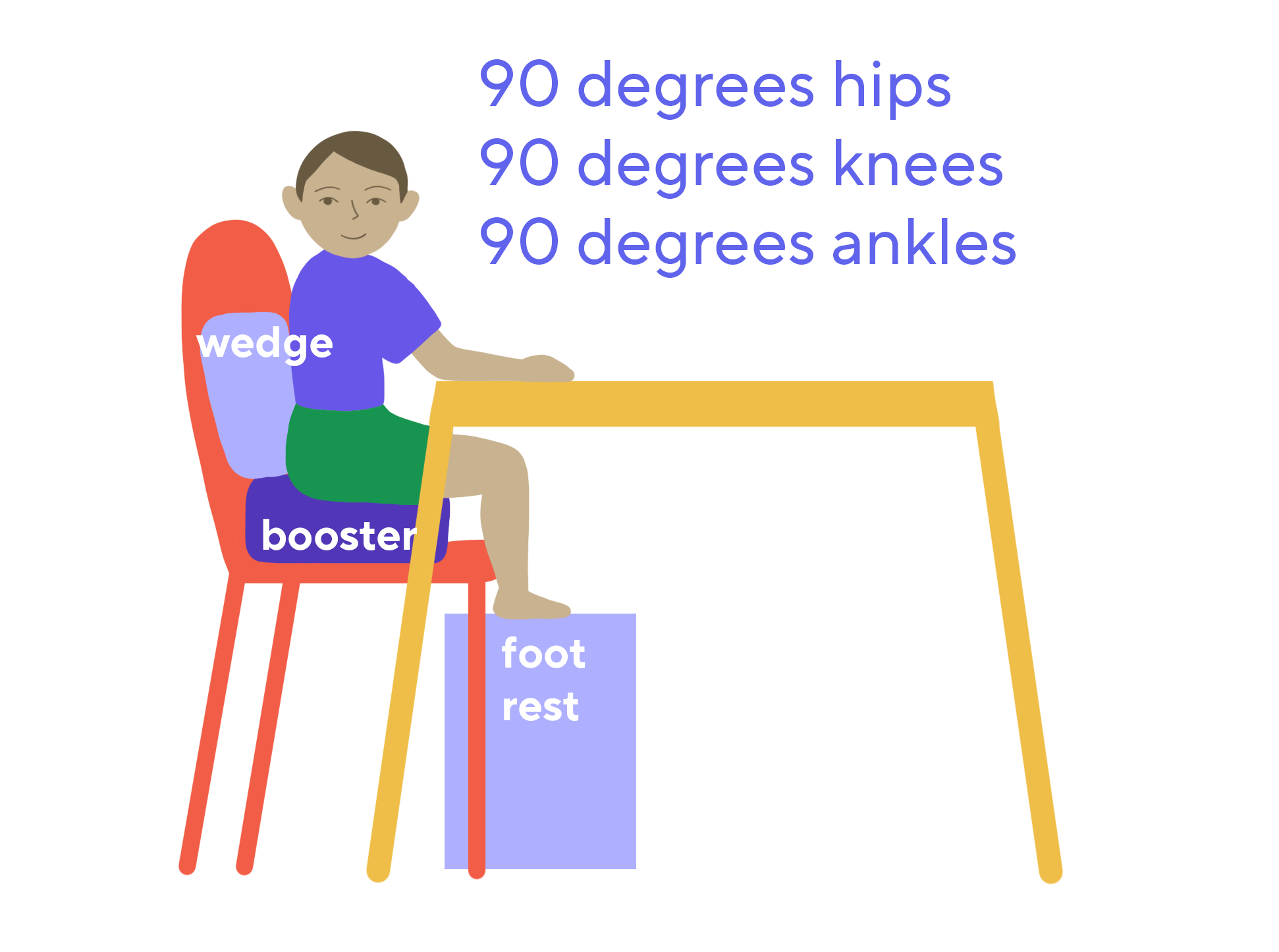

A child’s positioning in their chair:

Many children on the autism spectrum’s core muscles of the stomach and back are weaker than their peers, and some have poor body awareness [22]. That is, they don’t quite sense where their bodies are in space. This can result in poor posture, wriggling and discomfort while sitting at the table. By providing postural support, you can help your child focus on their eating rather than on keeping their body on the chair. If you see your child slouching, leaning or wriggling in their chair, try placing rolled up towels around the back and hips to provide additional support or consider investing in a more supportive chair with arms. Make sure that the feet are supported too. If their feet don’t reach the floor, try placing a step stool in front of the chair and under the table.

Try to sit together at a table for meals: As much as possible, it is beneficial for a family (even when it is just the child and one adult) to eat together as a matter of routine. Environmental cues help all children learn what they are supposed to be doing. For example, a child’s bed is an environmental cue for sleeping. Similarly, the family table needs to be that cue for eating. In addition, eating together helps your child learn through imitation. Children are wired to imitate others and a child will be more likely to put a new food in his or her mouth after watching a loved one do the same.

Photo by Tanaphong Toochinda on Unsplash

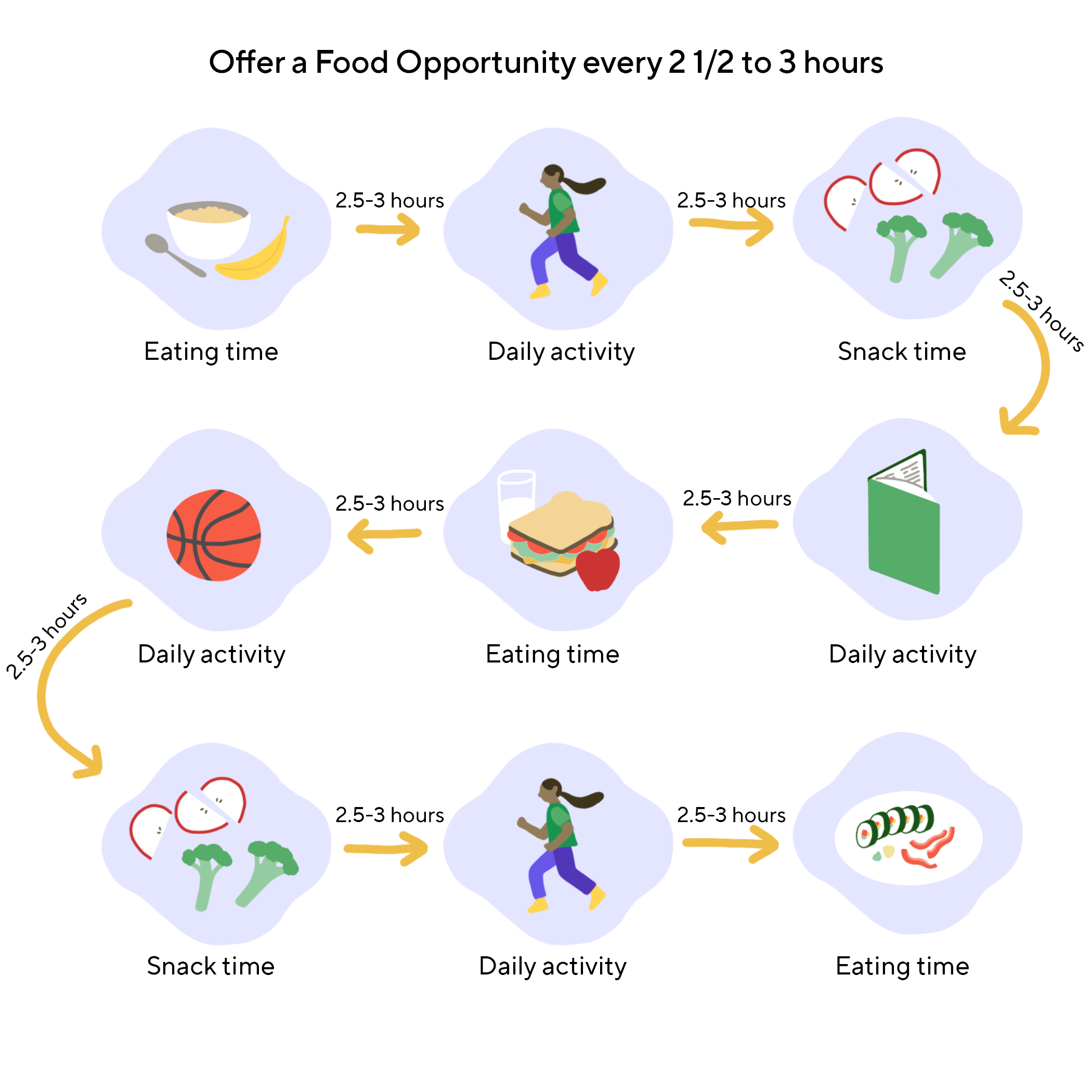

Have set times for meals and stick to them: This is probably the toughest strategy to implement but one that most often leads to increased acceptance of foods into the diet. Offer the meal or ‘food opportunity’ every 2.5 to 3 hours. Try to gradually decrease and eventually eliminate giving all snacks and drinks in between. The idea is to help train the child’s internal hunger signals to specific mealtimes. This helps the child’s body expect food and accept food at designated times. Also, it is a good idea to try and limit the amount of time the child spends at the table to a maximum of 20 minutes.

- Use Visuals: Some children may benefit from using visuals (visual schedules, calendars, social stories or narratives) to prepare them for mealtimes as they may feel a greater sense of control if they are able to predict what is coming up during their day.

.png?sfvrsn=28344872_1)

Research indicates that food avoidance issues can improve over time[5], and that intervention can help increase variety in foods and promote healthy eating[3]. Keep in mind that feeding is a journey that almost always involves triumphs and setbacks and, for some kids, it will take six months to a year to see consistent progress. Do not get discouraged and continue to expose your child to new foods!

Please also see our handout “BEST Strategies” for a handy document that summarizes the tips and strategies presented in this toolkit here.

Additional Suggested Resources/References

Articles

Crowley, J. G., Peterson, K. M., Fisher, W. W., & Piazza, C. C. (2020). Treating food selectivity as resistance to change in children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 53, 2002-2023.

Dominguez, P. R., Gámiz, F., Gil, M., Moreno, H., Márquez Zamora, R., Gallo, M., & Brugada, I. (2013). Providing choice increases children’s vegetable intake. Food Quality and Preference, 30, 108-113.

Ledford, J. R., Whiteside, E., & Severini, K. (2018). A systematic review of interventions for feeding-related behaviors for individuals with autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 52, 69-80.

Books

Williams, K. E., & Foxx, R. M. (2007). Treating eating problems of children with autism spectrum disorders and developmental disabilities. PRO-ED, Inc.

Williams, K. E., & Seiverling, L. (2018). Broccoli boot camp: Basic training for parents of selective eaters. Woodbine House.

Online Resources

Seiverling, L., & Williams, K. (2016). Clinical Corner: Improving food selectivity of children with autism. Science in Autism Treatment, 13(4), 16-20. Retrieved from: https://asatonline.org/research-treatment/clinical-corner/improving-food-selectivity/

References:

- Cermak, S.A., C. Curtin, and L.G. Bandini, Food selectivity and sensory sensitivity in children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 2010. 110(2): p. 238-246.

- Sharp, W.G., D.L. Jaquess, and C.T. Lukens, Multi-method assessment of feeding problems among children with autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 2013. 7(1): p. 56-65.

- Bandini, L.G., et al., Changes in food selectivity in children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of autism and developmental disorders, 2017. 47(2): p. 439-446.

- Bandini, L.G., et al., Food selectivity in a diverse sample of young children with and without intellectual disabilities. Appetite, 2019. 133: p. 433-440.

- Reinoso, G., et al., Food selectivity and sensitivity in children with autism spectrum disorder: a systematic review defining the issue and evaluating interventions. New Zealand Journal of Occupational Therapy, 2018. 65(1): p. 36.

- Nicely, T.A., et al., Prevalence and characteristics of avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder in a cohort of young patients in day treatment for eating disorders. Journal of eating disorders, 2014. 2(1): p. 1-8.

- Chistol, L.T., et al., Sensory sensitivity and food selectivity in children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of autism and developmental disorders, 2018. 48(2): p. 583-591.

- Herndon, A.C., et al., Does nutritional intake differ between children with autism spectrum disorders and children with typical development? Journal of autism and developmental disorders, 2009. 39(2): p. 212-222.

- Marshall, J., et al., Features of feeding difficulty in children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. International journal of speech-language pathology, 2014. 16(2): p. 151-158.

- Ranjan, S. and J.A. Nasser, Nutritional status of individuals with autism spectrum disorders: do we know enough? Advances in Nutrition, 2015. 6(4): p. 397-407.

- Schmidt, J.D., et al., Decreasing pica attempts by manipulating the environment to support prosocial behavior. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 2017. 29(5): p. 683-697.

- Advani, S., et al., Eating everything except food (PICA): A rare case report and review. Journal of International Society of Preventive & Community Dentistry, 2014. 4(1): p. 1.

- Call, N.A., et al., Clinical outcomes of behavioral treatments for pica in children with developmental disabilities. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 2015. 45(7): p. 2105-2114.

- Matson, J.L., et al., Pica in persons with developmental disabilities: Characteristics, diagnosis, and assessment. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 2011. 5(4): p. 1459-1464.

- Leader, G., et al., Feeding problems, gastrointestinal symptoms, challenging behavior and sensory issues in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of autism and developmental disorders, 2020: p. 1-10.

- Rose, D.R., et al., Differential immune responses and microbiota profiles in children with autism spectrum disorders and co-morbid gastrointestinal symptoms. Brain, behavior, and immunity, 2018. 70: p. 354-368.

- Kang, D.-W., et al., Long-term benefit of microbiota transfer therapy on autism symptoms and gut microbiota. Scientific reports, 2019. 9(1): p. 1-9.

- Martínez-González, A.E. and P. Andreo-Martinez, Prebiotics, probiotics and fecal microbiota transplantation in autism: A systematic review. Revista de Psiquiatría y Salud Mental (English Edition), 2020.

- Kinnaird, E., et al., Eating as an autistic adult: An exploratory qualitative study. PloS One, 2019. 14(8): p. e0221937.

- Panossian, C., et al., Young adults with high autistic-like traits displayed lower food variety and diet quality in childhood. Journal of autism and developmental disorders, 2021. 51(2): p. 685-696.

- Solish, A., et al., Effectiveness of a modified group cognitive behavioral therapy program for anxiety in children with ASD delivered in a community context. Molecular autism, 2020. 11: p. 1-11.

- Minshew, N.J., et al., Underdevelopment of the postural control system in autism. Neurology, 2004. 63(11): p. 2056-61.