Preamble: Reflections on Safety from a Parent to Parents…

This toolkit was written by a parent of a minimally-verbal young man on the autism spectrum. When her son was young, there were fewer resources and support professionals available and much of her success was found by trial and error. Here, she shares the lessons that she has learned, and provides helpful insight and suggestions for how to deal with some pressing safety concerns that parents face. It is her hope that parents who read this toolkit come away with a better understanding of why their child might struggle with staying safe in certain situations, and that parents can be more proactive in having safety plans in place.

Introduction

The safety of autistic individuals is a lifelong concern. Many autistic individuals are vulnerable to potential dangers within the home and community. Autism is a developmental disability with a range of levels of support requirements. Many autistic individuals have difficulties with communication, or may struggle with processing issues that can make it difficult to assess high risk activities or recognize dangerous situations. Steps can be taken and provisions put in place to avoid high risk situations and help in times of crisis. Safety concerns can be addressed and taught in various ways, including modelling situations, using visuals aids and sharing social stories.

Being proactive is fundamental in planning for your child’s safety. It is helpful to think about possible scenarios and decide on the likelihood of something happening based on what you know about your child. Think of it as a flowchart with ‘Yes/No’ and ‘If/Then’ pathways. For instance, if a scenario is that your child is getting away from you at a grocery store, you can think about the aisles that they are likely to go to (e.g., candy aisle first, arts and crafts aisle second). Then you can think about what you should do if they are not in those aisles (e.g., contact the manager and ask for help locating your child).

Many parents/caregivers have a plan regarding safety. Creating a safety plan well in advance of an alarming event will allow the execution of a well thought out plan that hopefully results in a happy ending to a scary event. Taking the time to create a list of information is important. Helpful information on the list comprises various items such as potential dangers or risks, personal contacts, and actions to take. This could go into the safety plan you write for your child.

A range of things need to be considered when creating a safety plan. Two important aspects of safety are (1) having strategies to maintain safety, and (2) having a plan for if/when an event happens that jeopardizes the person’s safety.

The following four components are essential when exploring safety:

- Predictability – Being able predict a possible unsafe situation.

- Proactivity – Safeguards that can be utilized in advance to avoid an unsafe situation.

- Prevention – Steps taken in an unsafe situation. For instance, can the individual with the disability be taught safety concerns? Or does the family or caregiver need to always be aware of the individual’s actions?

- Preparedness - A step-by-step safety plan of execution is ready in the event of an unsafe event.

An individual’s cognitive ability will determine elements of the safety plan. In developing the plan, focus on the child/youth’s developmental age rather than chronological age, particularly if they experience cognitive challenges. Spend time researching and deciding what would be helpful your child and family during a potentially unsafe occurrence. Reach out and explore relevant strategies, processes and resources in your community (e.g., what does the fire department do when a child is lost?). Customize your safety plans to suit your family’s needs. You do not need to reinvent the wheel, just make the wheel work for you and your family!

What is a Safety Plan?

A safety plan is a personalized, practical plan to seek safety for an individual. This plan should include key/critical information that is specific to a range of possible situations. A good safety plan will help you prepare for and respond to various situations. It is also important to share the safety plan with friends and family.

Create a safety plan during a time when you are feeling calm. A safety plan is a living document, meaning that it can be refined and improved over time as you learn more about what works or does not work. Ask your support network (such as trusted others) to review the plan so that they can support you and know better what to do, if needed.

Some of the preparations or steps in a safety plan might seem obvious, but it can be hard to think clearly or make logical decisions during moments of crisis. A good safety plan can help one stay focused if feeling overwhelmed in a crisis and/or a stressful time.

Identify Supports

Generate a list of people that you would be comfortable with you/your child contacting if help was needed. These could be extended family members, teachers, close family friends, etc. Show your child how to contact those people if they are unable to contact you and need help in an emergency. Also, ensure that your child is aware of their own name, name(s) of parent(s), phone number, and address.

In the following sections of the toolkit, various areas of risk and considerations for safety are outlined. These are meant to be ideas or examples to consider as you work through your own safety considerations and planning.

I. Physical Safety

A. Bolting

Also referred to as Wandering, “Elopement”, Fleeing and Running, Bolting can occur across a vast array of settings. Some autistic children may bolt as a means of exploring, coping with demands and anxieties, and/or escaping sensory discomfort.

- A common example of bolting is a child leaving their home to explore the neighborhood without informing their parent.

- Some autistic children are attracted to water, and accidental drownings are a significant cause of death in autistic children. The attraction to water is usually based in sensory processing differences, as swimming and floating can be soothing. Water safety is an important skill to teach an autistic child.

- Certain seasons can lead to a higher incidence of bolting. In colder weather, doors are often locked and windows are typically closed, which deters one form leaving the house. But if doors are unlocked and windows are open, which may happen more frequently in warmer weather, departure from a home is easier.

Remember that it takes just a split second for a child to walk away, for instance, while a parent is on the phone or shopping in a grocery store. In both cases, the child may have no understanding of the possible dangers or consequences. Being vigilant and having a plan is so important!

B. Unsafe Habits

What is a habit? A habit is an action that we do automatically in response to some cue because we associate that cue with an action and/or an outcome. For example, getting into a car and buckling one’s seatbelt is a habit. Getting into the car is the cue that helps make buckling a habit. Generally, the more times one repeats a behavior it becomes a habit. Learning to buckle your seatbelt is a safe habit while refusing to buckle your seatbelt is an unsafe habit and illegal.

Habits generally can be categorized as good or bad, appropriate or inappropriate and safe or unsafe. Autistic children often have communication delays, difficulties understanding social cues, and differences in sensory processing. All of these elements may contribute to the development of unsafe habits. The sooner support or intervention can occur to help an autistic person communicate, develop social skills, and seek appropriate means to satisfy their sensory needs, the safer they will be.

In intervention, a key goal is to determine what purpose an unsafe habit serves and replace it with behavior that leads to a safer habit. It is good to spend time observing a child and see how they interact with and react to various stimuli in the home and in the community. While observing, try to determine the function/purpose of the habit for your child. Is the action safe or unsafe? For example, when a child sees the burning flame of a candle, are they attracted to the flame and want to explore or even touch the flame? The child may not be able to understand the consequences of touching a burning flame. In fact, the ability to sense heat or cold can be difficult for some autistic children. The child may only see the flickering flame and not realize its risk of danger.

Replacing a habit likely will take time and may require considerable trial and error in order to figure out exactly why a child is doing something, and then choosing an appropriate and safe substitute for that behaviour. Consulting with a clinical team can offer support toward eliminating unsafe habits and replacing them with safe habits.

________________________________________________________

As previously mentioned, understanding the function of a behaviour is important if you are to replace it with a healthier one. For many autistic people, sensory processing differences can lead to unsafe behaviour. If someone is experiencing ‘sensory overload’, they may react strongly to certain stimuli. Some autistic individuals can be sensitive to loud noises, bright lights, certain foods, or struggle with being in places with lots of sensory input, like busy shopping centers. It can be difficult for an autistic child to try to filter or process all the incoming stimuli. The may feel out of control and be unable to regulate their emotions.

Some autistic individuals are ‘sensory seekers’, meaning they engage in behaviours that provide them with a sensory. Sometimes it is because they are trying to ‘drown out’ a sensory experience they find unpleasant, and sometimes it is because they are underwhelmed and engage in a behaviour to ‘feel something’. For more information on the different types of challenges, sensory issues and tips, see additional AIDE Canada toolkits such as:‘Sensory Processing Differences’, and ‘Understanding Complex Self-Injurious Behaviors’ ‘Toolkits.

It is important to remember that sensory seeking behaviours may provide the autistic individual with a means of seeking satisfaction or relief. Others might see the behavior as strange or unusual, but to the individual it may be fulfilling a purpose. As you spend time with an autistic individual, you may notice patterns of behavior which can sometimes lead to unsafe habits. It is useful to spend time determining the function of a behavior, and how it has developed or potentially could develop into a potentially unsafe habit. Hopefully, with the collaboration of a clinical team, its function can be understood, and a plan can be set to nurture a safer behaviour.

Learning to carefully observe and ‘pick your battles’ is especially useful when evaluating or assessing behavior. A question to ask is… “Is a particular behaviour unsafe or potentially unsafe, or simply unique?”

________________________________________________________

Biting as An Example of an Unsafe Habit: Biting is a challenging behavior that can be expressed by children. In typically developing children, biting is seen as an aggressive behavior. In children on the autism spectrum, biting can be seen as either aggressive or self-stimulating behavior. Most often, children with autism who bite (either themselves or others) do it for self-stimulating purposes. As previously mentioned, many children on the autism spectrum are affected by sensory processing differences.

Before you can reduce or eliminate biting behavior, it is necessary to determine what function it serves. Once a caregiver understands why a child bites, it is much easier to apply an intervention. For instance, when a child is seeking oral stimulation, replacement items that are appropriate for biting might be an option. Raw carrots, celery, chewing gum, or ‘chewlery’ (jewelry made specifically for chewing) might be appropriate substitutions. If the child is seeking to centralize pain or discomfort, anxiety reducing exercises might be helpful.

Until the biting habit has ceased, it is imperative that these children are not left unattended around other children for any amount of time. Biting can be an incredibly stressful behavior for both parent and child to overcome. However, with patience and dedication to interventional support, it is possible to redirect this behavior.

Pica – Another Unsafe Behaviour or Habit: Pica is an eating disorder characterized by a tendency to eat substances that provide no nutritional value such as soil, chalk, hair, paper, peeled paint from walls, and, in some cases, substances ingested can be harmful.

If you notice your child is continuously putting inappropriate non-food substances in the mouth, consult with your physician and clinical team. Your physician may suggest doing bloodwork to see if there are any nutrient imbalances that may be contributing to the unsafe eating habits. Your physician and clinical team can guide you in strategies to resolve this disorder. Please see our ‘Feeding Issues’ toolkit for more information.

Personal Reflection on Unsafe Habits…

“I noticed my son was extremely focused on seeking and putting fine hairs in his mouth. He would crawl across the room and find a hair and pick it up and run it through his fingers, then put it in his mouth with great satisfaction. This seeking and finding pattern was occurring in the home and in the community. It was happening everywhere!!! He was too young to understand the potential danger or the inappropriateness of his behavior, so I just spent time next to him with a watchful eye. Basically, I learned to pick my battles and sure enough within time, the hair seeking and putting it in the mouth faded, never to be seen again.

There was a replacement behavior coming up the back stretch. The new sensory seeking behavior was tearing paper. My son would spend hours tearing paper in long strips. It was odd and inappropriate, but was it dangerous? No, it was not harming him at all.”

______________________________________________________

“On a beautiful summer day, my son and I went for a walk in the neighborhood and had a picnic in the local park. Our wagon was packed with food and toys to enjoy at the park. My son always enjoyed pulling a loaded wagon. Our occupational therapist told me that pulling a wagon probably provides my child with sensory satisfaction.

While walking along the way, we were singing songs and nursery rhymes. For the most part, everything was nice and safe. My child has the unique ability to see things which I do not spot as quickly. What happened was concerning… As we were crossing the road, my child noticed a broken piece of a cookie on the road. He bent down and picked up the broken cookie and put it in his mouth. Instantly, my reaction was to stop him and immediately get that cookie out of his mouth. Fortunately, I was able to have him spit out the cookie and no harm happened. We carried on to the park and enjoyed our outing.

From this incident, I realized the need to help my child understand the danger of putting inappropriate things in his mouth. Again, I tried my best to help him understand with concrete examples of what is and is not safe. However, on one occasion I was at the dog groomers with our service dog and as I was at the cashier. I looked over and saw my son eating a gingerbread biscuit made for dogs. Well, it’s an edible looking cookie, not on the road but on a tray next to the cashier. I just thought to myself, get the cookie away from him and explain to him that these cookies are meant for dogs and not people. Once again, spend time getting to know the child was so needed…Observe your child as much as possible and note their unique styles. Reach out to others to help address safety concerns.”

Communication challenges are common in autism. The inability to ask for help adds risk, but also raises the importance of ingenuity in ensuring safety. As your child gets older, there are more possibilities for potentially unsafe situations. It is important to set up safeguards to help the child/youth navigate the environment, and build skills to remain safe.

Dealing with unsafe behaviors is particularly challenging. Seek the advice of a clinical professional to help understand the behavior, and get a better grasp of what exactly is being sought by child in the behavior. From that point, the task is to implement programs to teach replacement behaviors which are socially appropriate and safe.

C. Awareness of Surroundings

1. TRAFFIC and ROAD SAFETY

Autistic individuals can struggle with awareness or may appear to not be aware of their surroundings, including the people around them. It is important to teach your child the basics about traffic rules and road safety from an early age. A helpful way to start this task is to show and explain basic road signs and teach that traffic lights… “green means go, yellow means slow down, and red means stop”. Have good learning tools in place, like videos, graphic diagrams of road signs, toy dolls acting out actions like crossing the street, etc. Consult with your clinical/support team, and design strategies to reinforce traffic and road safety to your child. There are plenty of online resources and excellent learning videos to teach road safety. Make the teaching examples as real as possible. It is a good time to introduce the concepts of right and left, and looking both ways both ways before crossing the road. It is useful to teach your child the difference between a car on the road and a car moving on the road. For instance, you could teach, “A parked car is not going to harm you, but a moving car could”. Use tools and examples that fit for your child.

As your child gets older you may want to introduce navigation tools like a GPS to assist in getting around the community.

When in the car with your child, you can talk about the traffic, road signs, and safety on the road. They may not indicate that they are listening, but over time the concepts may be increasingly absorbed. The more exposure and repetition you provide your child, the more likely they will learn the important concepts. Be patient and continually move to greater safety.

2. WEATHER

One area of safety is learning how to dress appropriately, according to the weather. Weather awareness can be a real safety concern, particularly in extreme weather conditions (e.g., during a storm, exposure to extreme sun, extreme cold). Many autistic people struggle with how to dress for extreme weather for three main reasons:

- Sensory processing differences: Nerve receptors that tell a person when something is too hot or cold can be dampened in autistic individuals. For example, a person may not realize that they are too cold and are going to get frostbite if they don’t cover up because that information is not being processed by their brain.

- Clothing preferences/habits: A person may prefer to wear a certain article of clothing and may not want to have their routine adjusted because the weather has changed. For example, a child may prefer to wear heavy sweaters even though they may overheat in the summer. Some parents describe how difficult the transitions between seasons are because their child will resist changes like needing to wear long pants and a jacket once the weather gets colder.

- Abstract information processing: Some autistic individuals have difficulty in filtering and processing information that is of an abstract nature. Weather is an abstract concept because it has so many variables that influence how we experience and respond to it. It can be a struggle to get some autistic children to recognize how weather affects them and ultimately how they need to protect themselves. For example, they may know that people use an umbrella in the rain, but don’t use an umbrella when in a torrential rainfall.

The hope in teaching weather awareness is that it will lead to safety and greater autonomy. One way to make this happen is to break relevant concepts down into concrete steps. It is a good idea to begin with basics like ‘hot and cold’ or ‘sunny and cloudy’ or ‘windy and calm’. A caregiver can model by pairing the weather with the appropriate article of clothing (e.g., “it is a windy day so we should bring a jacket”). You will notice whether your child is successfully learning when they can pair weather with clothing choices. There are helpful teaching tools like weather apps and YouTube clips.

Try to work on one task at a time, keep the steps simple, and use plenty of positive reinforcement. If necessary, consult with a professional who can assist in developing a plan for self-dressing according to the weather. An occupational therapist can ensure that the child has suitable dexterity, grasping ability and general strength to get dressed (e.g., buttons, zippers, socks, etc.). A psychologist or behavioral specialist can provide programs that teach weather conditions and appropriate clothing, and a speech pathologist can advise on communication strategies to explain these concepts. There are numerous resources online to help teach this functional skill. Upon learning these skills, you could have your child select the correct type of clothes to wear in different weather conditions.

Personal Reflection…

“My son was taking an abnormally long time getting dressed in the morning. All the skills needed for self-dressing were learned, and he knew where to locate his clothes. After breakfast, he would go to his bedroom to get ready for the day; but he would just sit on his bed and not initiate dressing. Consulting with our clinical team, a program was designed to promote self-dressing that was relevant to the weather. I explained the weather app to my son, and we used this information in decisions about the next day’s clothing. Clothes were selected the night before and placed on a chair in his room. All the information was presented in a checklist style form. Within a few days, he was independently executing every step on the list in a timely manner. His understanding of how to dress for the weather added to his autonomy. Later he was able to successfully generalize to the selection of appropriate outerwear. I praised my son and told him that I was very proud of him.”

3. AUTISM SERVICE DOGS

Autism service dogs provide greater safety and independence for individuals who have the tendency to bolt. The dogs also are reported help an individual in several other ways:

- sensory regulation

- companionship

- help with sleep disturbance

- stress and anxiety reduction

- social facilitation with peers

- safety and independence

An autism service dog can provide the family and the child with greater public safety. Autism service dogs wear a uniform indicating their role as a working service dog and not a pet. In some instances, the dog may be tethered to a belt worn around the child’s waist. This helps to prevent the child bolting into traffic or getting lost in a busy and crowded shopping centre. Careful supervision by the parent is important to ensure that no adverse events or accidents occur.

Additionally, autism service dogs may also be trained to help detect seizures and alert families when one is about to occur or has occurred. The dogs can also guide individuals to a safe place prior to a seizure and help prevent injury during the seizure.

It usually takes two years to train an autism service dog. It is particularly important that an autism dog have International Public Access status, which grants the dog the ability to accompany the child wherever they go.

II. Community Safety

- Strangers

Some autistic people can be vulnerable to dangerous people and situations; thus, teaching them who is a stranger and how to be safe in those encounters is very important. But teaching this concept and appropriate responses can be particularly challenging. The idea of strangers and how to interact or avoid them is an abstract concept – one that is not easily grasped by some autistic people. Always work within the intellectual capabilities of your child, and have patience and work at your child’s pace.

One approach might be to teach by grouping people into ‘categories’: family members, friends, and strangers. You could show photos of key people in your child’s life, and emphasize who is a stranger, a friend, etc. Then you could delve into the concept of strangers; be clear in teaching that there are levels to someone being a stranger. There can be people that are “strangers with a purpose” who can be found either outside in the community or inside the home (e.g., store clerk, appliance repair person). Within the home, a respite worker or aide is someone that they may not know well, but has a purpose to help with a particular task or to spend time with them. It can be helpful to set the expectation ahead of time that a person named “___” will be coming over, what they are doing while they are there, and how long they will be spending time with the child.

For an example of a stranger outside the home, you can talk about a waiter at a restaurant as a stranger with a purpose in the community and that their job is to take your food order and bring you food. You can describe and model ways of interacting, and teach that it is appropriate to exchange social niceties, carry out bill payment for purchase, and then say “goodbye”. Then you can follow up after the interaction, and explain why it was okay to speak with that stranger. Practice, role plays or social stories may help to teach your child about means of engaging with strangers with a purpose.

The next category of strangers with a purpose is particularly important to teach about. This group entails strangers that can be engaged with when in trouble such as policemen, firemen, doctors, nurses, school staff/faculty, and security guards.

As your child reaches adolescence, there are areas of concern that become more pressing, such as personal space in public restrooms or on public transportation. Personal space must be respected, and if there is a potential for personal violation. It is important to learn skills to respond and resolve risky or problematic situation. You could use role modelling, video clips or social stories to illustrate such situations. Do some online research, seek out resources in your community, and consult with your child’s clinical team for educative approaches and resources.

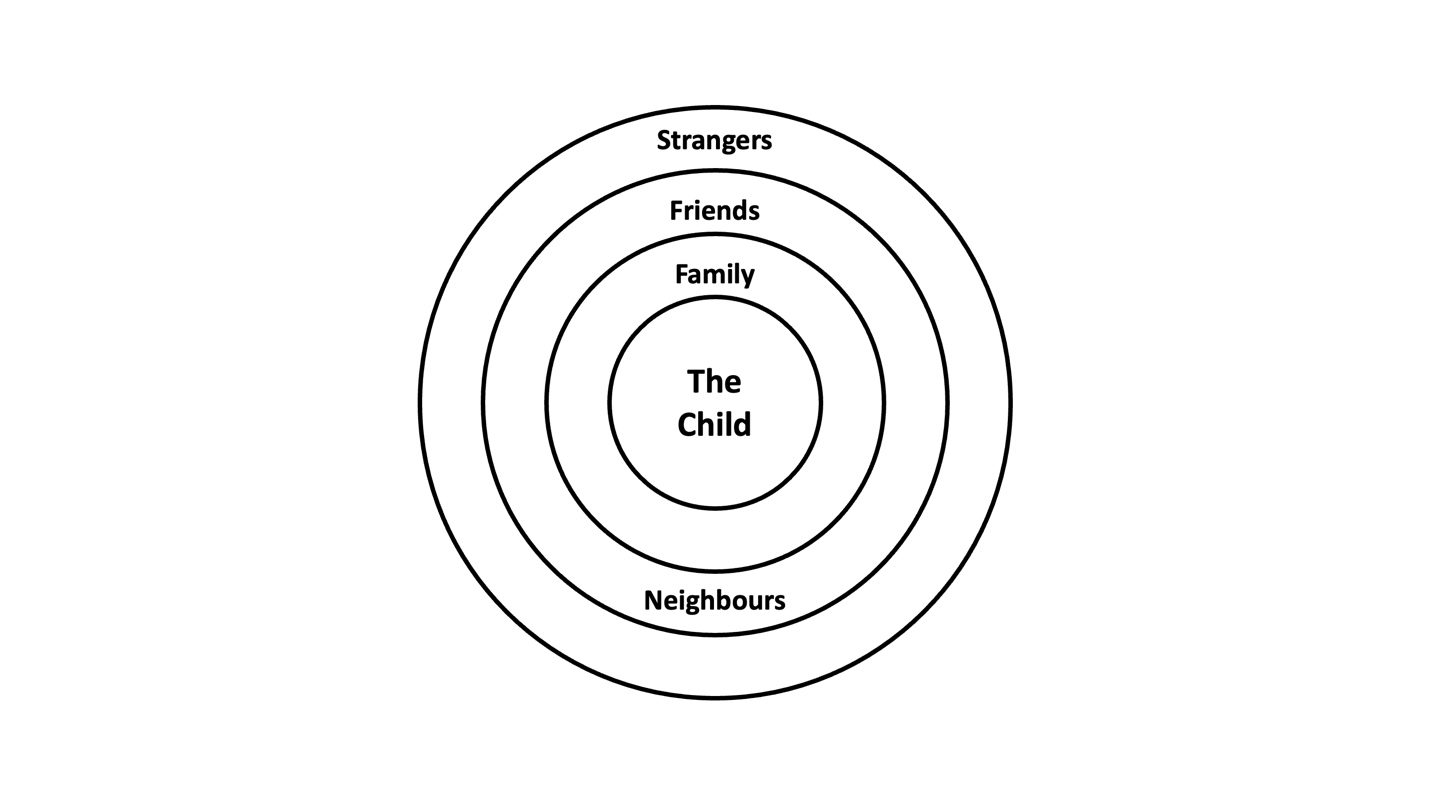

Another way to introduce your child to stranger awareness is to use “Privacy Circles”. This is a concept that is explained in the book ‘Navigating the Social World’ by Jeanette McAfee, M.D. The book uses a diagram that consists of an arrangement of circles from smallest to largest, with your child in the centre. The next circle would be your child’s immediate family, followed by extended family members like grandparents, aunts, uncles, etc. The further out the circles are from the centre, the less familiar the people become. The most outer circle is a stranger. It’s a useful and practical tool for teaching your child stranger awareness.

“Privacy Circles Program” image adapted from “Navigating the Social World” by Jeanette McAfee, M.D., Future Horizons Inc., January 1, 2002.

III. Professional and Caregiver Safety

Professional Safety

Along the journey in seeking supports for your child, parents will likely come across claims that state things like, “if you do this or invest in that regimen, things will get better”. There are various quick fixes and costly programs that claim success, with no or dubious evidence to back up their claims. Unfortunately, most often, the results you were looking for are not achieved and you are out of the money that was spent.

An important way to prevent your family from being taken advantage of is to learn more about the scientific research in an area. Initially, you must learn the basics of autism; become educated to what is autism and how it relates to you and your child. Look for studies that are peer-reviewed and published in respected scientific journals. These studies have been under scrutiny; hence, are more credible. Find out what specialists are being taught about a topic. For example, if you are worried about your child’s reactions to certain sensory stimuli (e.g., bright lights), find out what an occupational therapist who specializes in sensory processing differences is taught about the issue.

As you get to know other families in your community and begin to share information, you will hear about various ideas or resources. It can be difficult to sift through the claims. The advice of other parents and professionals you trust can be helpful. Also, check with your local autism society and meet support workers. There are reputable research foundations you can contact via the web, and reading the content on the AIDE Canada site will offer you ideas and resources.

Personal Reflection…

“My days were busy with therapy sessions and school related issues for my child. I was exhausted maintaining a household, caring for other family members and attending to all the various other chores and challenges. Needing help, I joined online groups and read about what parents had tried and had good results. I consulted with my child’s Speech Language Pathologist on the alternative therapies I was hearing about in groups. I was told about evidence-based practices versus programs being marketed without any scientific evidence. I was urged to do my due diligence in researching the credibility of claims. As time went on, I saw incremental progress in my child’s communication and was glad that I followed evidence-based practices. Also, as I learned more, I slowly was able to generate a new confidence and realize that evidence-based strategies for autistic children, teens and adults are the safest for my son.”

IV. Interpersonal Safety

A. Friendship and Safe Relationships

Having friends can provide immense joy and comfort. Yet some people with autism can have a hard time meeting people and making friends. One needs to have social skills to “meet and greet” and then seek out whether there is potential for a friendship. But social skill can be taught. A Speech Language Pathologist can help you with this communication part by designing social scripts and working on “WH” questions (the Who, What, Where and Why questions that are helpful in learning about a person who could be a potential friend). A Psychologist/Behaviorist can provide guidance in teaching about emotions like happy, sad, mad, etc. The more exposure you can provide your child, hopefully a more comfortable presence will be developed in social situations. Look for group settings like social clubs that encompass your child’s interest. Being able to interact with peers that share a common interest is a nice way to meet a potential friend. Look for facilitated settings where there is a group leader observing and lending a hand during interaction. For example, board game clubs which meet regularly can lead to friendships and the development of social skills.

It is important to help your child understand the different types of friendship and how to recognize when someone is not being a good friend. Below are different types of negative or in some cases, ‘non’ friendships which are important for children/youth/adults to learn about and be able to navigate.

- Toxic friendships

Your child may meet friendly people who share interests and they may become friends. Sometimes, things can break down and result in a toxic, or unhealthy relationship. Talk to your child about paying attention if they are starting to feel insulted, belittled, hurt, used, or mistreated. Remind them that these are extremely negative emotions, and nobody deserves to be treated that way. If they notice that they feel worse about themselves every time they are with a person, that is a sign that the friendship has become unhealthy. It is important to know the cues of such a relationship and if in doubt, individuals should be taught to heed their instinct and talk to a trusted person. Let them know that this doesn’t mean they have to stop being friends with a person altogether (otherwise, they may choose to keep quiet about their friend’s behaviour). Explain that there are ways to be proactive like setting boundaries and asserting safety and one’s interest in the relationship. Let your child/youth/adult know that if the other person doesn’t respond with respect and understanding, that may indicate that the relationship needs to end. Help from a trusted source may be needed in these situations.

- Toxic romantic relationships

As youth mature, many expect an interest in dating and romantic relationships. This will introduce new social skills, guidelines and ways of being. Assisting your youth/young adult in learning about appropriate sexual behaviour is very important. Perhaps early dates could be chaperoned until a degree of confidence and comfort is established. Or as a parent/support person, you could let the youth/young adult know that you are there to respond as needed.

Just as with toxic friendships, your child needs to be aware of whether their romantic relationship is healthy or unhealthy. Finding supportive resources are important. Items such as social narratives may be helpful in teaching and reinforcing safety.

- Toxic friendships

- Bullying at School

Children attend school to learn and develop. For a child to thrive and learn, they must feel safe and supported. Positive social interactions are fundamental in helping a child/youth feel good about themselves. When it comes to bullying, it may be helpful to look at the interaction from the perspective of the bully and the person being bullied. As a social hierarchy, people with autism wrongly may be placed lower on the perceived social hierarchy and may be victimized. Autistic people can appear more withdrawn or anxious, may struggle with social interaction, may have difficulty with problem-solving in high-stress situations, and may not have strong emotional regulation skills. The bully may pick on these differences, and seek to control and manipulate. Bullies want to exert their physical, verbal, or social power over the victim. But whatever the reason or background, bullying is wrong and must be halted!

If you see changes in your child’s behavior, like being more anxious, irritable, or withdrawn, it is possible that bullying is behind it. Pay attention and do some preliminary investigation into why there may be behavioral changes. If it turns out that your child is being bullied, the emotional pain that your child is enduring is heartbreaking and can lead to depression and/or isolation. Consult with your school principal, teachers, and support staff about your concerns, and intervene to bring an end to this negative experience. Ask whether there is an anti-bullying program in the school. Children and youth need to be taught that people with disabilities are very aware when they are being mistreated and bullying is not tolerated! The school should be creating an environment of inclusion rather than exclusion, with acceptance of diversity and no tolerance to bullying behaviors.

Finding support for your child who has experienced negative experiences is recommended. Online resources include PREVNet (https://www.prevnet.ca).

- Sexual Abuse

The topic of sexual abuse is a difficult yet important topic to be aware of, and if possible, to discuss with your child in an age-appropriate way through their developing years. There are sexual predators who see individuals with developmental delays as vulnerable and, for that reason, a target. For children who struggle with communication, being able to tell others about risk and concerning experiences is important, but can be a challenge. The abuse can take place anywhere -- at school, home, a recreational facility, etc., and by anyone who has access to your child. This isn’t meant to frighten readers, but to highlight that we all need to pay attention for signs of risk or that abuse has happened. Be aware of behavioral changes that might be a result of sexual abuse. You know your child best… look for signs that raise ‘red flags’. Find resources that highlight risk factors and ‘red flags’.

It is a good idea to teach and expand on the topic of sexual abuse in childhood, adolescence and during the transitional years to adulthood. As children get older, it is important to discuss healthy and unhealthy sexual practices. Consult with local community resources and professionals in your area and seek online resources.

V. Online Safety

A. Phishing/Scams

There are countless phishing websites and online activities that scam innocent people by gaining personal information which can lead to identity and/or financial theft. These scamming sites and schemes seek to deceive people and prey on a person’s judgement. They often appear as legitimate and claim to offer helpful advice or services. We need to teach children, youth and adults that if an offer from a stranger is ‘too good to be true’, it indeed likely is not legitimate and can be unsafe. They need to learn caution when spending time on the internet.

Phishing websites usually attract people that are trusting. People with developmental and intellectual disabilities can fall victim to online scamming. It is important to talk about the dangers of online scams, and remind your child that when in doubt, always seek the advice of a parent, caregiver, or another trusted person. Many autistic people are detailed orientated and honest. If you teach them what to look for when online, they may become astute in recognizing when a website is illegitimate and to be avoided. They need to be taught if there is a logical reason for what they are being asked about. It’s important to remember and teach our loved ones that we can step away from the computer if feeling unsure or pressured. The more we can educate ourselves and others about online safety, the less likely we will be scammed.

B. Predators (sexual)

The internet is laden with information – some good and some bad. In terms of upholding safety, it is important to recognize that the internet has opened doors to predators who seek to hurt and take advantage of innocent people. Online sexual predators are looking to lure trusting people; hence, we must ensure vigilance in teaching others to be cautious. Challenges in communication and social skills common in some people on the autism spectrum can make them more likely targets for online predators. Your child may stumble upon a chat forum or dating site unintentionally, and find themselves being asked unsuitable personal questions. Privacy settings can be set on a computer to prevent children and youth getting onto sites deemed sexually inappropriate. You can have conversations with your child to discuss social online etiquette, what to avoid, and how to proactively respond as needed. The more proactive you can be in teaching your child appropriate social and online behavior, the more prepared they will be in sensing a ‘red flag’. Consult with relevant resources such child welfare and cyber safety resources, and law enforcement and police services, so you can learn more about proactive means to ensure cyber safety. Contact police for advice and input in situations of concern.

VI. Financial Safety

The financial safety of autistic individuals is important. Ensuring education and support to manage financial resources is a priority. Safeguards can be put in place to ensure financial protection for someone with challenges in making personal financial decisions and ensuring that predators do not have access to an individual’s finances. It may be advantageous for autistic adults and/or their caregivers to discuss these issues with a financial advisor and a lawyer, particularly in planning for ongoing financial wellbeing as caregivers/parents get older and may be less available to ensure financial support and/or protection. Depending on an individual’s understanding of finances and executive functioning and ability, it may be important to enact safeguards for their financial protection. The following skills/aptitudes merit education for youth/adults.

A. Not sharing financial details

Teach your child/youth that it is appropriate to be private about one’s finances. Sharing your financial status is socially unacceptable and more importantly is none of anyone’s business except for a parent, guardian, or trustee. Having a bank card may be a good thing for your child to have, with built in safeguards of withdrawal limits.

B. Financial literacy

Financial literacy skills need to be taught. Transitional life skills should include financial issues such as paying bills, rent/housing costs, buying groceries and entertainment. The emergence of such online capacity such as GoFundMe and Venmo online services can lead to misuse. Charitable giving and budgeting need to be addressed, as appropriate for the individual, family and context.

VII. Letting Go

A. Balance of letting go but staying safe

There comes a time in one’s journey as a parent/caregiver to sit back and enjoy the fruits of one’s labour. You have spent countless hours learning about autism and working to create a safe and resourceful community for your child. You may have attended many workshops about autism in the hope of finding some connection as well as growth and quality of life for your child.

There will come a time when you see the results of your work. You might observe your child at a crosswalk, looking both ways and will smile with pride. On colder days, you may witness your child putting on a winter coat, hat and gloves, and think to yourself “my child gets it”.

It is important to recognize these areas of growth, and recognize your child working toward the best of their ability.

A FEW FINAL TIPS FROM A PARENT TO A PARENT: “Keep a journal and discuss relevant details with your support staff/team of professionals. When thinking about various areas of safety, note instances of your child’s awareness and lack of awareness. Take heed of what agitates your child, and what soothes and calms your child. This information can help you better understand your child and their needs for safety seeking. Strategize safety plans. The more you learn about your child, the better equipped you will be at planning for and ensuring safety. Your team (e.g., service providers, teachers, etc.) can assist in better understanding your child’s interactions, tendencies and behaviors which will be helpful in creating safety plans.

Just as every individual is unique, so is every autistic individual. There are some general guidelines and common issues to anticipate and address. It is particularly useful to spend time observing your child and taking note of characteristics that make your child unique. Being able to track and hopefully come to understand your child’s specific needs and behaviors will help you to create a safety plan that contributes to their ongoing well-being.”