Fakhri Shafai, Ph.D., M.ED. | AIDE Canada

Dr. Karen Bax, C. Psych., Director, Mary J. Wright | Research & Education Centre at Merrymount, Assistant Professor, Faculty of Education | Western University

Elsbeth Dodman, Honours B.A. Autistic Self-advocate

The information in this toolkit was adapted from the Making Mindfulness Matter (M3) program. The M3 program was created by one of the toolkit’s authors, Dr. Karen Bax, and is an 8-week course where parents and their children participate separately in weekly, 90-minute sessions to explore self-regulation concepts and develop skills to improve reactions to stressful situations. These program materials were adjusted to provide families with a general understanding of issues related to self-regulation and concrete strategies to try at home. For more information about Dr. Bax’s work with the M3 program, please see resources listed below.

Chosen terminology: Throughout this toolbox we refer to “persons on the spectrum” or “Autistic persons”. We have chosen this language based on the recommendations of one of this toolkit’s authors, Elsbeth Dodman, an autistic self-advocate, and in agreement with recent research organization and journal guidelines. These terms encompass the previously used terms of individuals with autism, Asperger’s, and Pervasive Developmental Disorder (PDD).

This toolbox also uses the term ‘self-regulation’ instead of ‘emotion-regulation’ because self-regulation includes more than just controlling one’s emotions. Self-regulation is important for managing things beyond our emotions- like our behaviour, thoughts, and actions.

Introduction to Self-regulation

Self-regulation, or a person’s ability to manage their behaviour and emotions, is a set of skills that develop throughout childhood. These skills include being able to adapt in new or difficult situations. While everyone can struggle with self-regulation occasionally, many persons on the spectrum regularly have difficulties with controlling their reactions in stressful situations.

This toolkit is designed to provide families with an introduction to the brain structures involved in self-regulation, resources to help them talk about it with their children, and give an overview of strategies to try at home. Additional resources, including an overview of professional treatment options, are provided along with recommended reading and websites.

Evelynn is six-years-old and thrives on routine; her family tries to keep her informed about her day but when plans change suddenly, her chest gets tight and she feels upset. She has a hard time moving past the disappointment of change in her routine and this means she often spirals into a meltdown. Because Evelynn has difficulty expressing ‘I am upset’, her family has difficulty catching those moments and isn’t always prepared for a meltdown.

Developing self-regulation skills

Self-regulation skills do not come naturally to very young people, which is why it is not uncommon for toddlers to have an emotional meltdown when something doesn’t go their way (e.g. when they can’t have the ice cream they want right then). When things are unexpected, or plans change without notice, children who struggle with self-regulation may act out. Self-regulation also allows us to pay attention to something when we might be having a hard time staying focused, something that is also a struggle for young children.

With time, teaching and experience, our self-regulation skills slowly develop and people can manage their emotions, behaviour, and body when faced with a difficult or disappointing situation. These skills can be taught and modeled for children as a way to give them better tools so they can avoid acting on impulses or having a meltdown when they are overexcited or overwhelmed. While some people think self-regulation is the same thing as self-control, there are some important differences. Self-control usually refers to someone not acting on urges in social situations (e.g. not saying something offensive), but self-regulation is about managing what is happening inside the body, regardless of whether people are around or not.

The role of the mindfulness

Why is mindfulness a useful strategy to improve self-regulation skills? An important aspect of mindfulness is focusing attention on what is happening in the moment. Mindfulness also encourages one to focus on the sensations in their body and to pay attention to their thoughts without judgment. It provides us with a chance to put space between what is happening in the moment and choosing how we react. Being able to notice what is happening without reacting is extremely useful when building self-regulation skills. Regularly practicing mindfulness can help to make self-regulation more automatic instead of choosing to negatively react to difficult situations. This toolkit includes kid-friendly descriptions of mindfulness and simple, fun exercises to try to help improve self-regulation skills.

Self-regulation in the brain

Why are we learning about the brain if we are talking about self-regulation?

Behaviours are responses to signals sent by the brain to the body. Emotional meltdowns, panic, and aggression all are the result of the brain responding to some sort of trigger. If we want to control the behaviour, we first must understand where the signals are coming from and how we can change them. We will start by describing the structures involved in self-regulation before we can talk about strategies for adjusting their responses to difficult situations.

How should we talk about these concepts with our children?

After we describe the structures of the brain, we will introduce child-friendly terms to discuss these structures and concepts with your child. It can be helpful to use these terms when working with your child on developing better self-regulation skills.

Jun is eleven and she hates going to the dentist’s office; the high pitch whirring of the dentist tools and having another person standing over her, especially close to her head and face, is overwhelming. She knows she has to go to get her teeth cleaned but when she gets into the dentist chair she panics and tries to leave, often pushing or kicking out to get away. Jun’s family is worried that now that their daughter is older and bigger she could really hurt someone when she starts to struggle.

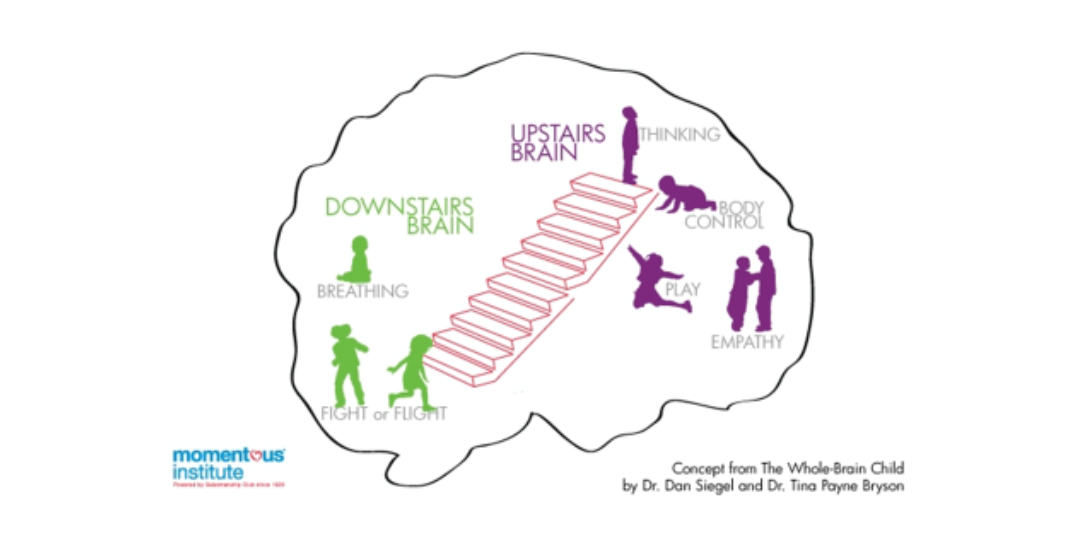

The Downstairs Brain vs. the Upstairs Brain

The brain can be divided into two main sections: the downstairs brain and the upstairs brain. These terms were coined by Dr. Dan Siegel, an expert on the biology of stress and adversity. The downstairs brain represents the ‘foundation’ of the brain and is the first section to develop. It is involved with aspects of survival like breathing, adjusting heart rate, and self-protection when in danger. The upstairs brain develops much more slowly- completing development at about 25 years of age. This region helps to control the downstairs brain.

Brain structures

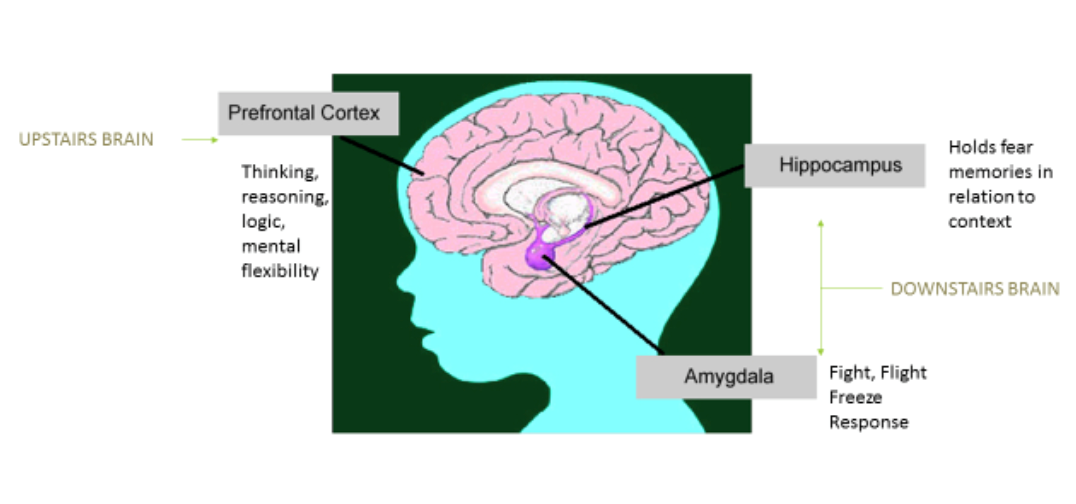

The Amygdala

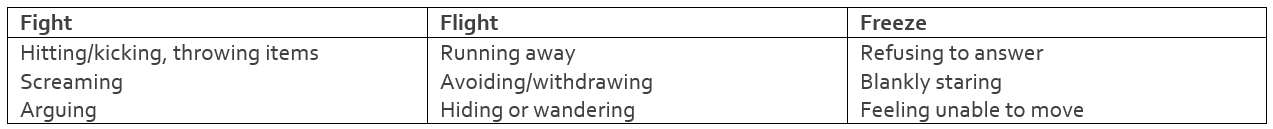

The amygdala is part of the downstairs brain and responds to situations that are unfamiliar, emotionally charged, exciting, painful, anxiety provoking, or fearful. This structure is activated when experiencing intense emotions, especially if someone is scared or worried about something. The amygdala is primed to notice ‘danger’ and will trigger ‘fight, flight, or freeze’ responses in situations that are very stressful. A person whose amygdala has triggered a ‘fight’ response may physically or verbally lash out. If someone is having a ‘flight’ response, they may run away or hide to get away from the situation. The ‘freeze’ response occurs when a person is unable to fight or flight, and so they stay frozen in place. When the amygdala is activated, a person may feel emotions like anger, rage, fear, worry, extreme happiness or excitability. The body may respond with heart pounding, sweating, increasing breathing rate, becoming less sensitive to pain, cold/clammy hands, dizziness or light-headedness, and/or difficulty concentrating.

The Hippocampus

The hippocampus is also part of the downstairs brain and is involved in storing and retrieving memories. It is especially important for sensory memories related to times the amygdala was activated to try and protect the person. It has many connections to the amygdala, and holds on to fear, anxiety, and stress memories in relation the context of a situation. It works to warn when there are signs that a person may be getting into a similar dangerous situation. It detects danger quickly and alerts the amygdala to act.

The Prefrontal Cortex

The prefrontal cortex is part of the upstairs brain and takes the longest to develop. It is the ‘smart’ part of the brain that uses logic and reasoning, conscious memories, awareness, detailed information, and flexible thinking. This is the part of the brain that allows us to think, learn, understand language, and make decisions. It helps to control the impulses of the downstairs brain. However, when the amygdala is activated, the prefrontal cortex is not able to control the downstairs brain as easily.

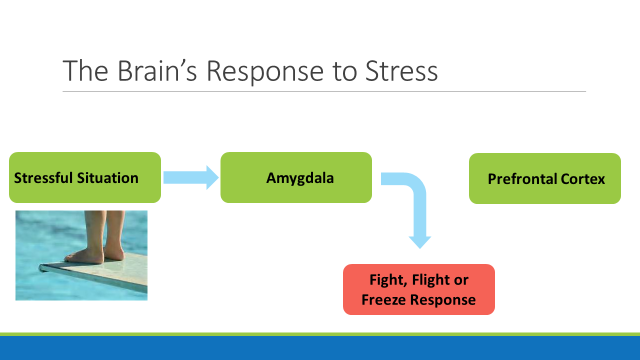

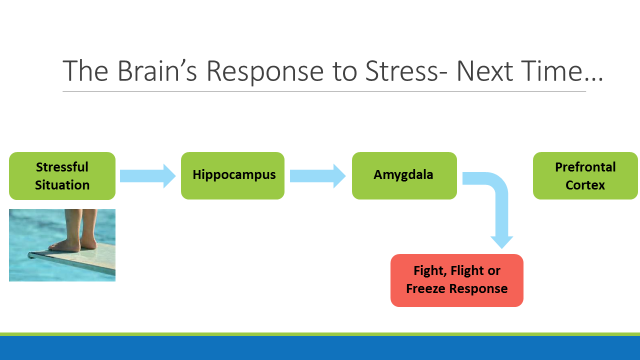

The Brain’s Response to Stress

Stressful moments, including new or unfamiliar situations, can lead to activation of the amygdala. For example, if the stressful situation is a child’s first time on a diving board, the unfamiliar setting may trigger the amygdala. This may result in heart pounding, increased breathing, and feeling lightheaded. If the amygdala activity is strong enough, the child may enter a ‘flight, fight, or freeze’ response and may run away from the diving board or be too scared to jump. The prefrontal cortex will have difficulty controlling the amygdala in this situation.

The hippocampus will store sensory memories relating to the surroundings (e.g. height of the diving board, the smell of chlorine, etc.) of the situation that caused the stressful response. These memories get recalled the next time the person is exposed to the same sensory information as a way to warn the person that they may be in danger. This may trigger the amygdala to respond with ‘flight, fight, or freeze’, which again will make it hard for the prefrontal cortex to control the activity of the downstairs brain.

Learning to control the downstairs brain

While it is difficult for the prefrontal cortex to control the downstairs brain, it is possible to strengthen it with practice. This works because the brain is ‘plastic’ or able to change its pathways based on its experiences. When we are born, the brain has billions of connections between neurons, or brain cells. As we develop, the brain will strengthen the pathways that are used the most frequently. A helpful analogy is if you imagine that you are in a forest and choose to go in the same direction day after day. With time, a small path will get bigger. With enough ‘traffic’ the path will widen into a gravel road, then a two-lane road, and if it is used enough, a large highway. Paths that are not used are not maintained and become overgrown.

Connections within the brain respond very similarly to ‘traffic’. The more often we respond to something in a particular way, the more likely our brain is to take that path. For instance, if someone usually responds to a stressful situation by yelling, the next time they are presented with a similar situation, they will likely respond by yelling. This reaction will strengthen the pathways that include the amygdala, making it more likely that ‘fight, flight, or freeze’ reactions become more automatic over time. It is not possible to entirely get rid of these pathways by erasing the connection. Rather, with practice, we can change which pathways we use by responding differently and strengthening the new connections over time.

The best way to change our more automatic, negative reactions in stressful situations (e.g. yelling) is to use techniques that help to strengthen connections to the prefrontal cortex. By regularly working on self-regulation skills, we can make larger ‘paths’ within the brain that allow to prefrontal cortex, or upstairs brain, to remain in control of the downstairs brain even when faced with difficult situations. The stronger the connections to the prefrontal cortex, the more likely it is for our brain to take those pathways to regulate our impulses and emotions.

Self-regulation in persons on the spectrum

As previously described, self-regulation is a skill that develops as we learn and grow. Self-regulation issues are common in persons on the spectrum and there may be multiple factors that contribute to their difficulties. Meltdowns can occur when a person is overwhelmed by a situation. It can be difficult to identify what is causing a specific meltdown, but with careful observation, it is possible to narrow down triggers and better prepare for stressful situations.

Devin is a five-year-old boy on the autism spectrum and he really struggles in new situations. When he doesn’t have experience or a frame of reference to fall back on, he isn’t sure what to do or what will happen. On his first day at his new school Devin cried and tried to run away from the classroom to hide in the hallway.

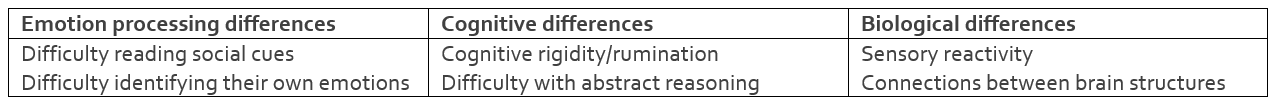

Autism traits that can contribute to self-regulation difficulties

There are multiple areas associated with autism that may play a role in difficulties with self-regulation. For instance, research has shown that it can be difficult for some people on the spectrum to recognize when they are experiencing a strong emotion or how another person is feeling. Cognitive differences can also contribute to self-regulation difficulties. Many persons on the spectrum struggle with flexible thinking and can ‘ruminate’, or continue to think about a stressful situation, which can lead to increased rates of anxiety and difficulty with problem solving skills.

Differences in connections in the brain may play a role in self-regulation difficulties for persons on the spectrum. Researchers have found both stronger and weaker pathways between the amygdala and other areas of the brain. These differences may be related to some persons on the spectrum finding certain situations frightening even if other people do not believe the situation is dangerous. Similarly, these different connections may help explain why some persons on the spectrum are seemingly unafraid in dangerous situations.

Additionally, sensory systems are processing information differently. Persons on the spectrum can struggle with recognizing sensory cues from their body, for instance, if their heart rate has increased or their muscles are tightening up. Being unable to recognize the physical indications of stress may contribute to autistic persons having difficulty recognizing when they are becoming upset until it is too late to stop the meltdown. Please see AIDE’s ‘Sensory Processing Differences’ toolkit for more information and suggestions for strategies to try at home.

Meltdowns

As previously mentioned, meltdowns occur when someone is overwhelmed. While we can’t always recognize a meltdown is going to occur until it has already started, there are some helpful and not-so-helpful ways that we can respond to meltdowns in the moment. It can be useful to reduce the amount of sensory input (e.g. turn off the TV), provide simple, non-verbal cues to use calming strategies (e.g. start taking slow, deliberate breaths yourself), and to use simple statements in a calm, quiet voice (e.g. “You seem upset. Let’s work on this together”). In the middle of a meltdown, it is not helpful to ask lots of questions about why they are upset, ask for eye-contact, or stop them from engaging in non-dangerous, self-soothing behaviours (e.g. rocking back and forth).

Talking to kids about the brain

It is helpful to use kid-friendly terms when talking about the structures of the brain that are related to controlling reactions. At the back of this toolkit is a handout with images that can be helpful to use when sharing these concepts with your child. It includes:

- The Wise Owl (Prefrontal Cortex): Helps us learn things and make good decisions.

- The Guard Dog (Amygdala): Looks out for danger and ‘barks’ to try and protect us. If the guard dog is barking loudly then the Wise Owl can’t do its job.

- The Huge Hippo (Hippocampus): Stores and remembers our experiences like a big filing cabinet, especially if there were strong feelings during that experience. The Hippo and the Guard Dog talk to each other whenever we are scared or upset.

- Downstairs Brain: Helps us to breath, change how fast our heart is beating, and protects us when we are in danger. The Guard Dog and the Huge Hippo live in the downstairs brain.

- Upstairs Brain: This is the ‘smart’ part of the brain that helps us to think and control our body. The Wise Owl lives in the upstairs brain and helps to keep the Guard Dog and Huge Hippo calm.

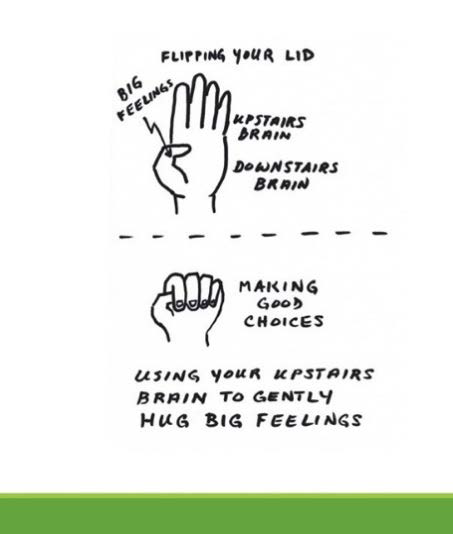

Flipping Your Lid: Hand Model of the Brain

Once children are familiar with the terms above, it is important to talk about what happens when the upstairs brain doesn’t ‘keep a lid’ on the downstairs brain. If someone is feeling big feelings, the Guard Dog will start barking and the Wise Owl will have a hard time getting it to quiet down. One helpful way to describe this concept is to just use your hand. As first described by Dr. Dan Siegel, the palm represents the downstairs brain, while the fingers represent the upstairs brain. ‘Big feelings’ are represented by the thumb. If the Guard Dog in the downstairs brain is barking too loudly, a person can ‘flip their lid’ and show their thumb, which means that they lost control of their big feelings. If, however, the upstairs brain is in control, it will ‘hug’ the big feelings and cover the thumb.

One of the advantages of using the ‘flipping your lid’ hand model is that it allows children to communicate how they are feeling without them needing to use their words. When someone is nearing the edge of an emotional meltdown, it can be difficult to share what is happening until it is too late. By having a hand signal, family members have a chance to support each other in containing their big emotions before they act out.

Mindfulness and Self-regulation

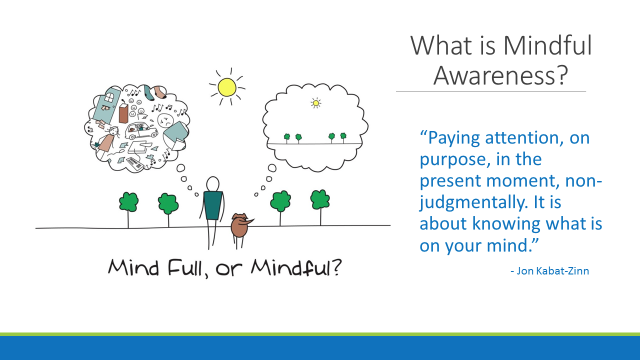

While many people think that mindfulness is the same as meditation, the two practices are very different. Meditation involves trying to ‘empty the mind’ and think of nothing. Mindfulness, however, is the practice of being in the moment and focusing awareness on our body sensations, feelings, thoughts, and surroundings without judgement. Mindfulness allows a person to be a gentle observer of both the environment and themselves.

The core features of mindfulness are the same features necessary for successful self-regulation. By learning how to direct one’s awareness in certain ways it is possible to notice and attend to negative emotions, our body’s reactions, and our behavioural responses. It also allows us to redirect our attention from those strong impulsive responses from the amygdala/downstairs brain to regulate our responses (emotional, behavioural, and physiological responses).

When Devin feels fear coming on in a new setting (tightness in his chest, feeling like he needs to run), he has learned to stop, take three deep breaths and list three things he notices in the new environment. By giving himself a moment to notice and count things in his environment, Devin has a chance to distract himself from feeling afraid. By paying attention to his body, Devin is able to slow himself down.

Mindful Awareness

When we are calm, we have greater access to our abilities to consider a situation, weigh out appropriate responses, and act thoughtfully and empathetically. While we are in a more calm and regulated state, we are playing an active role in choosing our thoughts and emotions.

It is important to note that mindful awareness skills do not prevent negative emotions; however, they help us respond more positively, and recover more quickly. Regular practice of mindful awareness is associated with lower stress hormones. This is not to say that there will never be meltdowns or acting out when strong emotions arise. However, the lower levels of stress hormones help to make reactions generally less extreme.

Mindful Practice in Everyday Life

There are two ways to practice mindfulness regularly. The first is through formal, seated mindfulness and involves mindful breathing for 1-2 minutes at a time, 2-3 times per day. Consistent formal mindfulness is associated with the most improvement in self-regulation skills in both children and adults. If one wants to strengthen those pathways to the prefrontal cortex and to reap the greatest benefits, it is important to carve out a few times a day to sit and practice mindful breathing.

Informal mindfulness refers to being mindful while doing daily routines (like showering or doing the dishes). It is helpful to use the senses to notice what is happening in each moment. For instance, in the shower, one can focus their attention on the temperature and sound of the water, the smell of shampoo, or the sight of water droplets spraying from the nozzle. Informal mindfulness is useful for taking mindful moments throughout the day. This helps us generalize the skills and become better accustomed to using mindful practices.

Your attention will wander during both formal and informal mindfulness practice. Being mindfully aware means that when you realize your mind has wandered or thoughts arose (frustrations, worry, stress, boredom, etc.), you acknowledge that this has happened and gently bring your attention back to the task at hand. Refocusing on the breath can help when redirecting the wandering thoughts.

Evelynn is working on catching herself before she reaches a meltdown when change comes. Evelynn uses slow rocking from foot to foot forward and back to help herself work through her feelings of upset. She also has started requesting tight hugs from her family members. Evelynn’s family has enrolled her in a children’s yoga class to help her be more aware of her body and how she’s feeling.

Mindful Breathing

Mindful breathing means sitting in a quiet, comfortable spot and slowly breathing in and out while paying attention to the sensations in your body (for example, the feeling of air moving through your nose). It is important to do deep ‘belly’ breaths so the stomach rises and falls, as this type of breathing is known to calm down the amygdala. Focused breathing also helps to calm our bodies by supporting our upstairs brain. As children practice mindful breathing, the brain reinforces the habit of responding to anxiety/stress using breathing.

Mindful Sensing

Mindful sensing means slowing down and paying attention to the world around using our senses. For instance, someone is practicing mindful sensing if they take a moment to enjoy the scent of a nice cup of coffee or stop to appreciate some beautiful flowers. By learning to take a break from our thoughts and just focus on experiencing the world as it is in that moment, we can strengthen the connections to the upstairs brain. For people with anxiety, mindful sensing can be helpful for replacing anxious thought patterns by redirecting attention to the sensations around them. Later on, there is a kid-friendly handout with suggestions for mindful sensing activities.

Mindful Movements

When we are aware of our body we are more connected to our actual experience. Mindful movement involves focusing your awareness on your body as it moves in different ways. This means noticing how your body reacts, and the thoughts and emotions that come with movements in your daily life. These movements include focusing on your posture and noticing how you feel when you move with your child (e.g. holding hands, giving a hug). Mindful movement also includes exercise performed with awareness, such as yoga, and mindful walking. When we focus on our body movements we can also calm our mind so that our prefrontal cortex is in charge and we can make better decisions. There is a kid-friendly handout with suggestions for mindful movement activities later in this toolkit.

Practicing mindfulness with kids

Mindfulness can be simply described as focusing attention on one thing at a time and really experiencing each activity that we do. When we are mindful, our Wise Owl can help us with our emotions and keeps us thinking in the moment. This means we are not focusing on what happened at school today, or what we are having for dinner tomorrow. We are only thinking about what is happening right now!

Mindfulness and the challenge of transitions

Transitioning between activities can be difficult for children with self-regulation issues and can result in poor impulse control, acting out, and/or emotional meltdowns. Some of the strategies discussed in this toolkit can help with the ease of transitions from one activity to the next by providing a calm signal that it is time to do something else. By consistently using these transition tools, eventually children can learn to develop better skills to regulate their reactions when they are asked to change tasks.

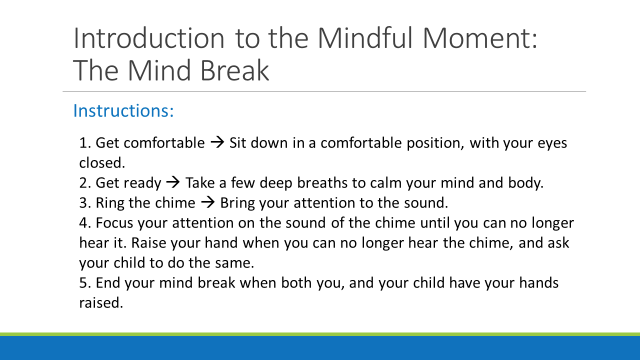

The Mind Break

The ‘mind break’ is a helpful practice for encouraging successful transitions from one activity to the next. To improve the likelihood of a relaxed transition to a new activity, it can be helpful to give children a count down before starting the mind break. For instance, let them know that in 10 minutes there will be a mind break and then they will be doing something new, and remind them again 5 minutes beforehand. If you don’t have access to a chime, there are some free applications that can be downloaded online.

Mindful Breathing

Mindful breathing connects us with our breath. A helpful activity to try with children learning mindful breathing uses a ‘Breathing Buddy’. Children begin this mindfulness activity by laying on the floor and putting a stuffed animal (or book for older kids) on their stomach. They are asked to breath in deeply to their belly so that the object rises and falls with each breath. The object gives them something to focus on and helps them recognize when their breath has changed speed. Try these instructions when you all practice mindful breathing together:

“Breath in through your nose and out through your mouth slowly and deeply”

“Pay attention to your belly rising and falling with each breath”

“If your mind wanders, it’s okay, just notice the thought and blow it away like a cloud.”

Mindful Sensing

Mindful sensing connects us with our senses. By trying different activities, we can be mindful through touch, hearing, smelling, seeing, and tasting. Paying attention to what we are seeing or hearing or touching when we are feeling upset can help us control our big emotions and keep the Guard Dog quiet. Children who are starting to feel overwhelmed can calm themselves down by naming one thing each that they can see, hear, feel, taste, or smell.

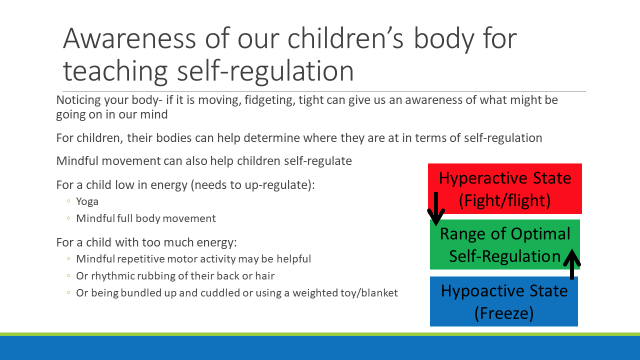

Mindful Movement

Mindful movement connects us with our body. When we pay attention to how our body is moving, we strengthen the connections to the Wise Owl. The way we move can either help us calm down or help us get more energy. For instance, when we are feeling sleepy we can try some yoga. Children who struggle to communicate with words can still communicate how they are feeling through their body language. By paying attention to their movements, parents can choose a mindful movement that will help them self-regulate and stay calm.

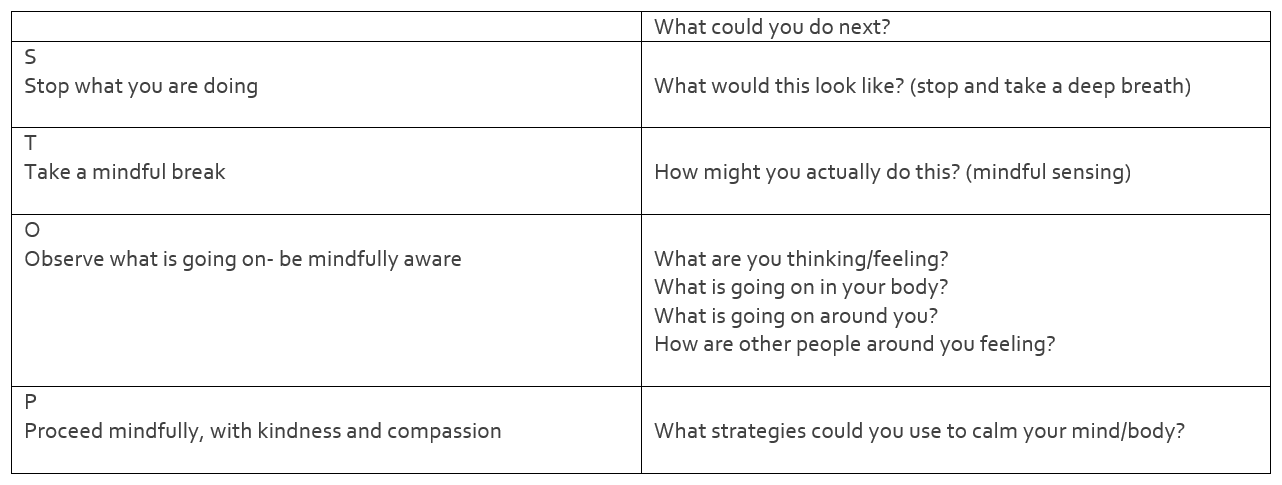

S.T.O.P. Model

Self-regulation allows a person to think before they speak or act. It can be difficult to control our big emotions and keep calm when we are upset about something, but with practice we can ‘pause’ how we are feeling and give ourselves a chance to make good choices.

Modeling Self-regulation for kids

As we have already discussed, the upstairs brain is still developing until the age of 25. The brain learns how it should react to certain situations by observing how others react. For instance, if a child sees a parent scream and run away from a spider, the child will likely scream when they see a spider. If children see their parent react that way frequently, the child is more likely to automatically react that same way in the future. If, however, parents respond to stressful situations calmly, the child is more likely to be calm when faced with that same situation. Parents hoping to model mindfulness for their children often find it helpful to imagine there is a video recorder in their child’s brain.

Mindfulness Talk at Home

If we want our children to practice mindfulness and learn better self-regulation skills, it is important to model that behaviour for them and use the mindfulness terms in everyday life. Pay attention to times when it would be useful to point out that the person is anxious or upset and then call attention to their feelings without anger or judgment. For instance:

• Help your child recognize when their guard dog is too loud and encourage them to take a breathing break

“Evelynn, I can see your guard dog is starting to bark, why don’t we get our breathing buddy so we can calm down and then we can figure out how to solve the problem together.”

• Model to your child when you need a breathing break

“Devin, my guard dog is getting in control, I am sorry I yelled. I am going to do a breathing break and then we can talk about this more calmly, when my wise owl is more in charge.”

• Stay in the present moment- not thinking about the past or future

“Jun, I know you are worried about saying your poem in class today, let’s use the chime so we can refocus on getting organized and out the door on time for school today.”

• Practice mindful awareness and breathing regularly

Following up after a meltdown

Despite our best efforts with practicing mindfulness, meltdowns will still occur from time to time. After the person has calmed down, it can be helpful to use the S.T.O.P. method described above to brainstorm ways that they could have handled it differently. Without anger or judgment, we can talk about when they could have stopped (S) before they reacted, how they could have taken a mindful moment or break (T), what they could have observed inside and outside of themselves (O), and what would have been a good choice when decided how to proceed with calmness and compassion (P). By providing constructive feedback, the person is able to plan a better way to respond in the future and may be able to choose that that path when faced with a similar situation.